“The child is a boy,” Guillemote whispered to me. “A bonny, healthy boy. A brother for little Edmund.”

I saw Owen at my bedside, the child in his arms.

“Here he is,” he said. “Just look at him. He’s perfect. Are you not proud of yourself to have produced such a child?”

“He is yours, too, Owen,” I said.

And I felt: everything…just everything is worthwhile for this moment.

We decided to call him Jasper. “Jasper of Hatfield,” I said. “Brother to Edmund.”

Edmund was brought to view his new brother. He looked with wonder at the small creature in the cradle.

“He is your brother,” I said. “You will always look after him, will you not?”

Edmund nodded gravely.

“You will always be good friends. You will always stand together. You will, Edmund, I know.”

“Yes,” said Edmund. And he repeated, “Brother Jasper.”

He hunched his shoulders, smiling, as though it were a great joke that he now had a brother.

THE MAID

Peace continued for a few weeks. Of course, we knew it could not last. We were prepared, for when the Cardinal had come to see me before Jasper’s birth, he had told me of the imminent coronation in France. It was becoming more and more apparent that I should be expected to be there, in view of the fact that I was French and sister to the man who was now calling himself King of France. I was not sure what part I should be expected to play. Owen thought it would depend on the state of affairs which existed between England and France at the time. They would perhaps want me very much in evidence. On the other hand, it could well be that they would want to keep me out of the public view.

“If this should be the case,” I said to Owen, “why should they be so insistent that I must go?”

“They are taking no chances.”

“Oh, Owen…must I go?”

“I do not see how it can be avoided. Your absence from the coronation at Westminster was acceptable. When the Cardinal visited you, you appeared to be unwell, so it was logical enough to assume that you were sickening for some illness. But if you plead illness again they will probably be sending doctors down to Hatfield to give a report on you. That could be very dangerous.”

“I suppose so many people have used illnesses as excuses that it can easily become suspect.”

“It is a good one if it can be substantiated.”

“You really think I must go, don’t you, Owen?”

“I am afraid, my love, that it would be highly dangerous not to do so.”

“And you, Owen?”

“It might be that I could come as a member of your household. You will surely be expected to take some of your servants with you.”

“If that were possible, I could bear it.”

“We shall have to make it possible.”

“We will. We will. Oh, but the children, Owen …”

“We cannot take them with us.”

“No…alas. They must remain. But to be separated from them. How long, Owen?”

“It will surely be some months.”

“I won’t do it. I won’t!”

“What excuse can you give?”

“That I am unfit to travel.”

“It will not work twice.”

“I will tell them the truth, then. I will say, ‘Leave me alone. Let me live my own life. I have my husband and my children…and my family. Rule this country as you will. Rule France too. But please do not try to rule me.’”

Owen took my hands and looked into my face.

“It is no use, Katherine, my love. Such talk will help us not at all. You will have to go or arouse suspicions. We cannot risk that. There must be no excuses this time. You must go as though it is a great pleasure to see your son crowned in your native land. It is the only way. It has to be done.”

“I can’t face it, Owen. Jasper has only just come to us. To leave him…to leave Edmund…for so long …”

“We have to do it. It’s no use fighting against it. And when it is over, we shall return to this quiet, idyllic life. It will be all the more wonderful to us. You will see.”

I wept silently.

“It is so hard to leave them…when they are so young.”

He stroked my hair as he held me tightly in his arms. “Think. You will be closer to Henry.”

“Henry is already lost to me. Do you think I shall ever be alone with him? I cannot see Henry now without seeing his crown. He is not so much my son as the King.”

“Yet underneath his ceremonial robes and crown, he is only a child. Remember that. He may want to talk to you. He may need your help. It may be that he needs you more than Edmund and Jasper do. They will be left in good hands. You need have no fear for them. Katherine, we have to face this. We dare do nothing else.”

I knew he was right. I had to prepare myself for separation.

I tried to explain to Edmund that I was going away, that I hated to leave him, but this was a matter of duty. He was not quite sure what that was, and I was touched by the way in which he clung to my skirts as though to prevent my departure.

“Guillemote will be here with you. And Jasper will be here.”

That cheered him a little. He adored Guillemote, and I think that when she was around he felt safe.

It would be natural for me to take a small entourage with me. Owen was in this, and so was Joanna Courcy. The other two Joannas with Agnes were staying behind to help Guillemote with the children.

I prayed that I would soon be back, but one could never be sure; and I doubted whether I should be received in France with the enthusiasm I had enjoyed when I rode with Henry at my side. The position had changed since then. I had not heard what was happening since the siege of Orléans, but I did know that there was a new spirit among the French and that the high hopes of the English had declined, with the result that there had been several French victories.

It was late February when Henry, after attending service in St. Paul’s asking God’s blessing on the proposed journey, made his way to Canterbury, where he was to spend Easter.

I, with my little entourage, joined him there.

I was formally received by him, but I saw his eyes light up with pleasure as they rested on me, and I knew he was glad that I should be near.

I did have an opportunity of being alone with him, and it seemed then that he set aside his crown and stepped out of his ermine robes to be my little son.

“I have missed you,” he said.

If only we could all be together! I was thinking of how I would introduce him to his half-brothers, Edmund and Jasper Tudor. If only that were possible! If only we could all be one happy family!

I laughed at myself. What an absurd flight of fancy. I wondered what Henry would say. They would have molded him to their ways. I supposed Warwick was, after all, following his instructions. Kings could not be kept at their mothers’ sides. They had to be brought up to ride, to shoot, to go into battle when the time arose. They were hurried through their boyhoods to make them quickly into men before they had had time to be young. They would say that was a woman’s view.

“I have missed you so much, too,” I said. “But I heard about your coronation.”

“Oh yes, I am truly King now. The Earl of Warwick says that a king is not truly a king until he is crowned.”

“Well, you are that now, my son. How like your father you are!”

“Am I?” he asked eagerly. “I have to be like him. They are always saying that. ‘Your father would have done this. Your father would have done that.’ That is what they are always saying. If I do not please them, they say that my father would be ashamed.”

“No, no,” I said quickly. “He would have understood. He was a great soldier, but he was a good, kind man as well.”

“I wish he had not died.”

“A great many people wish that.”

“If he were alive, I should not have to be King …”

I smiled at him sadly. “Your coronation must have been impressive.”

“It was so long…and there were so many speeches…so many things to remember.”

“But I heard you did your part well.”

“Did they say so?”

“Yes…everybody did.”

He looked pleased. “I thought the banquet would go on forever, and they were all watching me …”

“Well, they would, you being the King.”

“It is a strange feeling…to be a king.”

“Yes, it must be.”

“Why do you stay shut away in the country?”

“There is little I could do at Court.”

“You would be near me.”

“I would so rarely see you.”

“I wish …”

“Tell me what you wish. You are the King. It should not be so difficult for you to achieve.”

“What I wish no one could give me. I wish my father would come alive, and then I should not have to be the King.”

My poor Henry, weighed down with honors which he did not want! His dearest wish was to be robbed of his crown!

I was glad that kingship had not given him grand ideas of his importance. Rather it seemed it had had the opposite effect.

We stayed in Canterbury over the Easter week and then made our way to Dover. On St. George’s Day we were ready to cross to France. Cardinal Beaufort was a member of the party and he was in charge of the King’s person. Ten thousand soldiers had joined us at Canterbury and they were ranged on the shore, ready to board the vessels when the order was given.

The sun was shining as we went on board, and very soon, with a fair wind behind us, we were sailing for Calais.

We were blessed with a smooth crossing, and about ten o’clock on a bright and sunny morning we landed.

The Cardinal insisted that we ride at once to the church of St. Nicholas, where High Mass was celebrated.

We stayed a short while in Calais and then the Cardinal said that we should make our way to Rouen where he hoped to find the Duke of Bedford waiting for us.

I gathered that we should remain at Rouen while arrangements were made for Henry’s crowning at Rheims. It was an uncomfortable situation, as only recently my brother had been crowned and given the same title which was now to be bestowed on my son. I could sense, too, that there was a very different feeling among the soldiers from that which I had known when I came to meet that other Henry. Uneasiness had replaced triumph. I heard whispers of The Maid.

It was surprising to me that one woman—and a girl at that—could have so changed the outlook of people. In the towns and villages through which we passed we were regarded suspiciously. I knew that the soldiers were on the alert. This country was no longer meekly accepting the conquerors. In fact, the conquerors were on very uncertain ground. Could this all be due to one girl? She must have had divine help. Many believed that, and there was I being influenced in the same way as those superstitious people who thought that God had sent His help through the person of a country girl, to drive the English out of France.

I knew that the Cardinal was very uneasy.

I did not have much opportunity of speaking to him, but now and then he seemed to remember that I was the Queen and the King’s mother, and then there would be a little discourse between us.

He would not have spoken of his uneasiness if I had not insisted on doing so.

I said to him: “Are you anticipating trouble, Cardinal?”

He raised those haughty brows and looked at me in surprise.

“It is clear that something has changed here,” I insisted.

“In what way?”

“It would seem to me that the English are no longer regarded as the triumphant conquerors.”

“There have been a few setbacks, but nothing of any great importance.”

“So the fall of Orléans was of no importance?”

“It would have been better if it had not been allowed to happen.”

“The crowning of Charles …”

“An empty ceremony. The Duke of Bedford is a great soldier and a magnificent organizer. He has everything under control.”

“I suppose it is hard to dispel a legend of this sort which has risen up.”

“You are referring to the woman who dresses up in men’s clothes?”

“I did mean the one whom they call The Maid.”

“A momentary wonder. An exaggeration.”

“It seems to have put heart into the French and taken something from the English.”

“Whatever has been taken will be put back.”

I was not sure how much importance he attached to Joan of Arc, but I believed he was deceiving himself into thinking that she could have no effect on the war.

I soon discovered that he was by no means unconcerned about her, for as we marched through those villages, the change in the mood of the people was decidedly noticeable—and it seemed that a kind of despairing depression had fallen on our men.

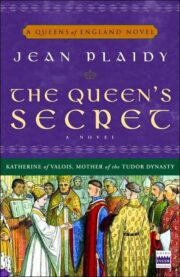

"The Queen’s Secret" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "The Queen’s Secret". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "The Queen’s Secret" друзьям в соцсетях.