I don’t say “Amen” to the prayer for the health of the queen, for I thought she was not particularly pleasant to me, and any child that she has will take my place as the next Lancaster heir. I don’t pray against a live birth, for that would be ill-wishing, and also the sin of envy; but my lack of enthusiasm in the prayers will be understood, I am sure, by Our Lady, who is Queen of Heaven and understands all about inheritance and how difficult it is to be one of the heirs to the throne, but a girl. Whatever happens in the future, I could never be queen; nobody would accept it. But if I have a son, he would have a good claim to be king. Our Lady Herself had a boy, of course, which was what everyone wanted, and so became Our Lady Queen of Heaven and could sign her name Mary Regina: Mary R.

I wait till my half brothers and half sisters have gone ahead, hurrying for their dinner, and I ask my mother why we are praying so earnestly for the king’s health, and what does she mean by a “time of trouble”? Her face is quite strained with worry. “I have had a letter from your new guardian, Edmund Tudor, today,” she says. “He tells me that the king has fallen into some sort of a trance. He says nothing, and he does nothing; he sits still with his eyes on the ground and nothing wakens him.”

“Is God speaking to him?”

She gives a little irritated sniff. “Well, who knows? Who knows? I am sure your piety does you great credit, Margaret. But certainly, if God is speaking to the king, then He has not chosen the best time for this conversation. If the king shows any sign of weakness, then the Duke of York is bound to take the opportunity to seize power. The queen has gone to parliament to claim all the powers of the king for herself, but they will never trust her. They will appoint Richard, Duke of York, as regent instead of her. It is a certainty. Then we will be ruled by the Yorks, and you will see a change in our fortunes for the worse.”

“What change?”

“If the king does not recover, then we will be ruled by Richard of York in place of the king, and he and his family will enjoy a long regency while the queen’s baby grows to be a man. They will have years to put themselves into the best positions in the church, in France, and in the best places in England.” She bustles ahead of me to the great hall, spurred on by her own irritation. “I can expect to have them coming to me, to have your betrothal overturned. They won’t let you be betrothed to a Tudor of Lancaster. They will want you married into their house, so your son is their heir, and I will have to defy them if the House of Lancaster is to continue through you. And that will bring Richard of York down on me, and years of trouble.”

“But why does it matter so much?” I ask, half running to keep up with her down the long passageway. “We are all royal. Why do we have to be rivals? We are all Plantagenets, we are all descended from Edward III. We are all cousins. Richard, Duke of York, is cousin to the king just as I am.”

She rounds on me, her gown releasing the scent of lavender as it sweeps the strewing herbs on the floor. “We may be of the same family, but that is the very reason why we are not friends, for we are rivals for the throne. What quarrels are worse than family quarrels? We may all be cousins, but they are of the House of York and we are of the House of Lancaster. Never forget it. We of Lancaster are the direct line of descent from Edward III by his son, John of Gaunt. The direct line! But the Yorks can only trace their line back to John of Gaunt’s younger brother Edmund. They are a junior line: they are not descended from Edward’s heir; they descend from a younger brother. They can only inherit the throne of England if there is no Lancaster boy left. So-think, Margaret! – what do you think they are hoping for when the King of England falls into a trance, and his child is yet unborn? What d’you think they dream, when you are a Lancaster heir but only a girl, and not even married yet? Let alone brought to bed of a son?”

“They would want to marry me into their house?” I ask, bewildered at the thought of yet another betrothal.

She laughs shortly. “That-or, to tell the truth, they would rather see you dead.”

I am silenced by this. That a whole family, a great house like York, would wish for my death is a frightening thought. “But surely, the king will wake up? And then everything will be all right. And his baby could be a son. And then he will be the Lancaster heir, and everything will be all right.”

“Pray God the king wakes soon,” she says. “But you should pray that there is no baby to supplant you. And pray God we get you wedded and bedded without delay. For no one is safe from the ambitions of the House of York.”

OCTOBER 1453

The king dreams on, smiling in his waking sleep. In my room, alone, I try sitting, as they say he does, and staring at the floorboards, in case God will come to me as He has come to the king. I try to be deaf to the noises of the stable yard outside my window and to the loud singing from the laundry room where someone is thumping cloths on a washboard. I try to let my soul drift to God, and feel the absorbing peace that must wash the soul of the king so that he does not see the worried faces of his counsellors, and is even blind to his wife when she puts his newborn baby son in his arms and tells him to wake up and greet the little Prince Edward, heir to the throne of England. Even when, in temper, she shouts into his face that he must wake up or the House of Lancaster will be destroyed.

I try to be entranced by God, as the king is, but someone always comes and bangs on my door or shouts down the hall for me to come and do some chores, and I am dragged back to the ordinary world of sin again, and I wake. The great mystery for England is that the king does not wake, and while he sits, hearing only the words of angels, the man who has made himself Regent of England, Richard, Duke of York, takes the reins of government into his own hands, starts to act like a king himself, and so Margaret, the queen, has to recruit her friends and warn them that she may need their help to defend her baby son. The warning alone is enough to generate unease. Up and down England men start to muster their forces and consider whether they would do better under a hated French queen with a true-born baby prince in her arms, or to follow the handsome and beloved Englishman, Richard of York, to wherever his ambition may take him.

SUMMER 1455

It is my wedding day-come at last. I stand at the door of the church in my best gown, the belt high and tight around my rib cage and the absurdly wide sleeves drowning my thin arms and little hands. My headdress is so heavy on my head that I droop beneath the wire support and the tall, conical height. The sweep of the scarf from the apex veils my pale resentment. My mother is beside me to escort me to my guardian Edmund Tudor, who has decided-as any wise guardian would, no doubt-that my best interests will be served by marriage to him: he is his own best choice as caretaker of my interests.

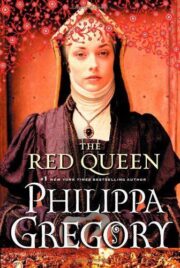

"The Red Queen" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "The Red Queen". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "The Red Queen" друзьям в соцсетях.