I put my hands to my hot cheeks. This is unbearable, but nobody notices my discomfort.

“Not another word,” Jasper says flatly. “She is a great lady, and I fear for her and her child. You get an heir for yourself, and don’t repeat gossip to me. The confidence of York with his quiver of four boys grows every day. We need to show them there is a true Lancaster heir-in-waiting; we need to keep their ambitions down. The Staffords and the Hollands have heirs already. Where’s the Tudor-Beaufort boy?”

Edmund laughs shortly and reaches for more wine. “I try every night,” he says. “Trust me. I don’t skimp my duty. She may be little more than a child herself, with no liking for the act, but I do what I have to.”

For the first time, Jasper glances over to me, as if he is wondering what I make of this bleak description of married life. I meet his gaze blankly with my teeth gritted. I don’t want his sympathy. This is my martyrdom. Marriage to his brother in this peasant palace in horrible Wales is my martyrdom; I offer it up, and I know that God will reward me.

Edmund tells his brother nothing more than the truth. Every single night of our life, he comes to my room, slightly unsteady from the wine at dinner that he throws down his throat like a sot. Every night, he gets into bed beside me, and takes a handful of my nightgown as if it were not the finest Valenciennes lace hemmed by my little-girl stitches, and holds it aside so he can push himself against me. Every night I grit my teeth and say not one word of protest, not even a whimper of pain, as he takes me without kindness or courtesy; and every night, moments later, he gets up from my bed and throws on his gown and goes without a word of thanks or farewell. I say nothing, not one word, from beginning to end, and neither does he. If it were lawful for a woman to hate her husband, I would hate him as a rapist. But hatred would make the baby malformed, so I make sure I do not hate him, not even in secret. Instead, I slide from the bed the minute he has gone and kneel at the foot of it, still smelling his rancid sweat, still feeling the burning pain between my legs, and I pray to Our Lady who had the good fortune to be spared all this by the kindly visit of the bodiless Holy Ghost. I pray to Her to forgive Edmund Tudor for being such a torturer to me, her child, especially favored by God. I, who am without sin, and certainly without lust. Months into marriage I am as far away from desire as I was when I was a little girl; and it seems to me that there is nothing more likely to cure a woman of lust than marriage. Now I understand what the saint meant when he said that it was better to marry than to burn. In my experience, if you marry, you certainly won’t burn.

SUMMER 1456

One long year of loneliness and disgust and pain, and now I have another burden to bear. Edmund’s old nursemaid becomes so impatient for another Tudor boy that she comes to me every month to ask if I am bleeding, as if I were a favorite mare at stud. She is longing for me to say no, for then she can count on her fat old fingers and see that her precious boy has done his duty. For months I can disappoint her and see her wizened old face fall, but at the end of June I can tell her that I have not bled, and she kneels down in my own privy chamber and thanks God and the Virgin Mary that the House of Tudor will have an heir and that England is saved for the House of Lancaster.

At first I think she is a fool, but after she has run to tell my husband Edmund and his brother Jasper, and they have both come to me like a pair of excited twins, and shouted their well wishes, and asked me if I would like anything special to eat, or if they should send for my mother, or whether I should like to gently walk in the courtyard, or to rest, I see that, to them, this conception is indeed a first step towards greatness, and could be the saving of our house.

That night, as I kneel to pray, at last I have a vision again. I have a vision as clear as if I were in my waking life, but the sun is as bright as in France, not Welsh gray. It is not a vision of Joan going to the scaffold, but a miraculous vision of Joan as she was called to greatness. I am with her in the fields near her home; I can feel the softness of the grass under my feet, and I am dazzled by the brightness of the sky. I hear the bells tolling the Angelus, and they ring in my head like voices. I hear the celestial singing, and then I see the shimmering light. I drop my head to the rich cloth of my bed, and still the blazing light burns the inside of my eyelids. I am filled with conviction that I am seeing her calling and I am being called myself. God wanted Joan to serve Him and now He wants me. My hour has come and my heroine, Joan, has shown me the way. I tremble with desire for holiness, and the burning behind my eyes spreads through my whole body and burns, I am sure, in my womb, where the baby is growing into the light of life and his spirit is forming.

I don’t know how long I kneel in prayer. Nobody interrupts me, and I feel as if I have been in the sacred light for a whole year when I finally open my eyes in wonder, and blink at the dancing candle flames. Slowly I rise to my feet, hauling myself up the bedpost, weak at the knees with my sense of the divine. I sit on the side of my bed in a state of wonder and puzzle at the nature of my calling. Joan was called to save France from war and to put the true King of France on his throne. There must be a reason that I saw myself in her fields, that all my life I have dreamed of her life. Our lives must march in step. Her story must speak to me. I too must be called to save my country, as she was summoned to rescue hers. I have been called to save England from danger, from uncertainty, from war itself, and put the true King of England on his throne. When Henry the king dies, even if his son survives, I know it will be the baby now growing in my womb who will inherit. I know it. This baby must be a son-this is what my vision is telling me. My son will inherit the throne of England. The horror of war with France will be ended by the rule of my son. The unrest in our country will be turned into peace by my son. I shall bring him into the world, and I shall put him on the throne, and I shall guide him in the ways of God that I shall teach him. This is my destiny: to put my son on the throne of England, and those who laughed at my visions and doubted my vocation will call me My Lady, the King’s Mother. I shall sign myself Margaret Regina: Margaret the queen.

I put my hand to my belly that is still as flat as a child’s. “King,” I say quietly. “You are going to be King of England,” and I know that the baby hears me and knows that his destiny and that of all England is given to me by God, and is in my keeping.

My knowledge that the baby in my womb is to be king and that everyone will curtsey to me supports me through the early months, though I am sick every morning and weary to my soul. It is hot, and Edmund has to ride out through the fields where the men are making hay, to hunt down our enemies. William Herbert, a fierce Yorkist partisan, thinks to make Wales his own while there is a sleeping king, and no one to call him to account. He marches his men through our lands and collects our taxes under the pretext that he is ruling Wales for the regency of York. Indeed, it is true that he has been appointed by his good friend the Earl of Warwick to rule Wales, but long before that, we Tudors were put here by the king, and here we stay doing our duty, whether our king is awake or not. Both Herbert and we Tudors believe ourselves to be the only rightful rulers of Wales, properly appointed; but the difference is that we are right, and he is wrong. And God smiles on me, of course.

Edmund and Jasper are in a state of constant muted fury at the incursions of Herbert and the Yorkists, writing to their father Owen, who is in turn riding out with his men, harrying York lands, and planning a concerted campaign with his boys. It is as my mother predicted. The king is of the House of Lancaster, but he is fast asleep. The regent is of the House of York, and he is only too lively. Jasper is away much of the time, brooding over the sleeping king like a poor hen with addled eggs. He says that the queen has all but abandoned her husband in London, seeking greater safety for herself in the walled city of Coventry, which she can hold against an army, and thinks that she will have to rule England from there, and avoid the treachery of the city of London. He says that the London merchants and half of the southern counties are all for York because they hope for peaceful times to make money, and care nothing for the true king and the will of God.

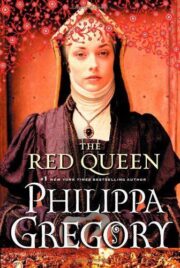

"The Red Queen" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "The Red Queen". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "The Red Queen" друзьям в соцсетях.