Meanwhile, every lord prepares his men and chooses his side, and Jasper and Edmund wait only till the end of haymaking, and then muster the men with their scythes and bill hooks and march out to find William Herbert and teach him who commands Wales. I go down to the gate of the castle to wave them farewell and bid them Godspeed. Jasper assures me that they will defeat Herbert within two days and capture Carmarthen Castle from him, and that I can look for them to come home in time for the harvest; but two days come and go and we have no news of them.

I am supposed to rest every afternoon, and my lady governess is ordered by my mother to take a renewed interest in my health, now I am carrying a child that could be a royal heir. She sits with me in the darkened rooms to make sure that I do not read by the light of a smuggled candle, or get down on my knees to pray. I have to lie on my bed and think of cheerful things to make the baby strong and blithe in his spirits. Knowing I am making the next king, I obey her and try to think of sturdy horses and beautiful clothes, of the magic of the joust and of the king’s court, and of the queen in her ruby gown. But one day there is a commotion at my door, and I sit up and glance at my lady governess, who, far from watching over me as the vessel preparing to bear the next king, is fast asleep in her chair. I get up and patter over to my door and open it myself, and there is our maid Gwyneth, white-faced, with a letter in her hand. “We can’t read it,” she says. “It’s a letter for someone. None of us can read.”

“My lady governess is asleep,” I say. “Give it to me.”

Stupidly she hands it over, though it is addressed to my lady governess and marked for her eyes alone. I break Jasper Tudor’s seal and open it. He has written from Pembroke Castle.

Edmund wounded and captured by William Herbert. Held prisoner at Carmarthen. Prepare for attack as best you can there, while I go to rescue him. Admit no strangers; there is plague.

Gwyneth looks at me. “What does it say?” she asks.

“Nothing,” I say. The lie comes to my mouth so swiftly that it must have been put there by God to help me, and therefore it does not count as a lie at all. “He says that they are staying on a few days in Pembroke Castle. He will come back later.”

I close the door in her face, and I go back to my bed and lie down. I put my hand on my fat belly that has grown bigger and now curves beneath my gown. I will tell them the news later tonight, I think. But first I must decide what to say and what to do.

I think, as always, What would Joan of Arc do, if she were in my place? The most important thing would be to make sure that the future king is safe. Edmund and Jasper can look after themselves. For me, there is nothing more important than ensuring that my son is safe behind defensible walls, so when Black Herbert comes to sack the Tudor lands, at least we can keep my baby safe.

At the thought of William Herbert marching his army against me, I slide down to my knees to pray. “What am I to do?” I whisper to Our Lady, and never in my life would I have been more glad of a clear reply. “We can’t defend here; there isn’t even a wall that goes all round, and we don’t have the fighting men. I can’t go to Pembroke if there is plague there, and anyway, I don’t even know where Pembroke is. But if Herbert attacks us here, how shall we be safe? What if he kidnaps me for ransom? But if we try to get to Pembroke, then what if I am ill on the road? What if traveling is bad for a baby?”

There is nothing but silence. “Our Lady?” I ask. “Lady Mary?”

Nothing. It is a quite disagreeable silence.

I sigh. “What would Joan do?” I ask myself. “If she had to make a dangerous choice? What would Joan do? If I were Joan, with her courage, what would I do?”

Wearily, I rise to my feet. I walk over to my lady governess and take a pleasure in shaking her awake. “Get up,” I say. “You have work to do. We are going to Pembroke Castle.”

AUTUMN 1456

Edmund does not come home. William Herbert does not even demand a ransom for him, the heir to the Tudor name and the father of my child. In these uncertain times nobody can say what Edmund is worth, and besides, they tell me he is sick. He is held at Carmarthen Castle, a prisoner of the Herberts, and he does not write to me, having nothing to say to a wife who is little more than a child, and I do not write to him, having nothing to say to him, either.

I wait, alone in Pembroke Castle, preparing for siege, admitting no one from the town for fear they are carrying the sickness, knowing I may have to hold this castle against our enemies, not knowing where to send for help, for Jasper is constantly on the move. We have food and we have arms and we have water. I sleep with the key to the drawbridge and the portcullis under my pillow, but I can’t say that I know what I should do next. I wait for my husband to tell me, but I hear nothing from him. I wait for his brother to come. I wish his father would ride by and rescue me. But it is as if I have walled myself in and am forgotten. I pray for guidance from Our Lady, who also faced troubled times when she was with child, but no Holy Ghost appears to announce to the world that I am the Lord’s vessel. It seems that there is to be no annunciation for me at all. Indeed, the servants, the priest, and even my lady governess are rapt in their own misfortunes and worries as the news of the king’s strange sleep and the struggle of power between his queen and the country’s regent alerts every scoundrel to the opportunity of easy pickings to be made in a country without government, and Herbert’s friends in Wales know that the Tudors are on the run, their heir captured, his brother missing, and his bride all alone at Pembroke Castle, sick with fear.

Then, in November, I get a letter addressed to me, to Lady Margaret Tudor, from my brother-in-law, Jasper. It is the first time in his life he has ever written to me, and I open it with shaking hands. He does not waste many words.

Regret to tell you that your husband, my dearly beloved brother Edmund, is dead of the plague. Hold the castle at all costs. I am coming.

I greet Jasper at the castle gate, and at once see the difference in him. He has lost his twin, his brother, the great love of his life. He jumps down from his horse with the same grace that Edmund had, but now there is only the noise of one pair of boots ringing iron-tipped heels on the stone. For the rest of his life he will listen for the clatter of his brother and hear nothing. His face is grim, his eyes hollowed with sadness. He takes my hand as if I am a grown lady, and he kneels and offers up his hands, in the gesture of prayer, as if he is swearing fealty. “I have lost my brother, and you, your husband,” he says. “I swear to you, that if you have a boy, I will care for him as if he were my own. I will guard him with my life. I will keep him safe. I will take him to the very throne of England, for my brother’s sake.”

His eyes are filled with tears, and I am most uncomfortable to have this big, fully grown man on his knees before me. “Thank you,” I say. I look round in my discomfiture, but there is no one to tell me how to raise Jasper up. I don’t know what I am supposed to say. I notice he doesn’t promise anything to me if I have a girl. I sigh and clasp my hands around his, as he seems to want me to do. Really, if it were not for Joan of Arc, I would think that girls are completely useless.

JANUARY 1457

I go into confinement at the start of the month. They put up shutters on my bedroom windows to close out the gray winter light. I can’t imagine that a sky which is never blue and a sun which never shines can be thought so distracting that a woman with child should be shaded from it; but the midwife insists that I go into darkness for a month before my time, as the tradition is, and Jasper, pale with worry, says that everything must be done to keep the baby safe.

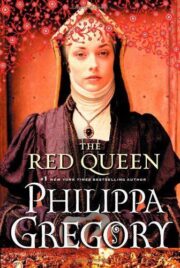

"The Red Queen" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "The Red Queen". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "The Red Queen" друзьям в соцсетях.