Another ladle of potato hit the next plate held out to her. She didn’t even look at the haggard face behind it as she doled out the food, or the one behind that, because she was too busy searching through the queue of people, seeking out one particular set of broad shoulders and pair of bright black eyes below eyebrows like wings.

‘Do pay attention, Lydia,’ Mrs Yeoman’s voice said cheerily beside her. ‘You’re being a bit overgenerous with the spuds, my dear, and though our good Lord managed to spread five loaves and three fishes among five thousand, we’re not quite so handy at it ourselves. I’d hate to run out sooner than we have to.’

A merry laugh rearranged the wrinkles on Mrs Yeoman’s face, making her look suddenly younger than her sixty-nine years. She had the leathery skin of a white person who has spent most of her life in the tropics and her eyes were almost colourless, but always smiling. They rested a moment longer on her young companion’s face, and then she patted Lydia’s arm before resuming the task of issuing bowls of rice gruel to the never-ending line of gaunt faces. It made no difference to Constance Yeoman their colour or their creed; all were equal and all were beloved in the sight of her Lord, and what was good enough for Him was good enough for her.

Lydia had been coming to St Saviour’s Hall every Sunday morning for almost a year now. It was a large barn of a place where even whispers echoed up to the high beamed ceiling, and dozens of trestle tables lined up in front of two steaming stoves. Mr Yeoman had come up one day from the flat below at Mrs Zarya’s and suggested with his usual missionary zeal that they might like to help out occasionally. Needless to say, Valentina had declined and said something about charity beginning at home. But later Lydia had crept downstairs, knocked on their door, breathed in the unique smell of camphor rub and Parma violets that permeated their rooms just as strongly as the hymns and the sad picture of Jesus at the door with a lamp in his hand and the crown of thorns on his head, and offered her services to their charity soup kitchen. At the very least, she reasoned, it meant she would receive one hot meal a week.

Sebastian Yeoman and his wife, Constance, might be retired from the church now, but they worked harder than ever. They begged, borrowed, and browbeat money out of the most unlikely pockets to keep their cauldrons simmering in the big hall behind St Saviour’s Church and every Sunday the poor, the sick, and even the criminal flocked through its open doors for a mouthful of food, a warm smile, and a few words of comfort offered in an astonishing variety of languages and dialects. To Lydia the Yeomans were the real version of Jesus’s lamp. A bright light in a dark world.

‘Thank you, missy. Xie xie. You kind.’

For once Lydia let herself look more closely at the young Chinese woman in front of her. She was all sharp bones and matted hair and was carrying an infant on her hip in a funny kind of sling, while two older children leaned listlessly against her. All were dressed in stinking rags and all had skin as grey and cracked as the dusty floor. The mother had the broad but fleshless face and thick brown fingers of a peasant who had been forced from her farm by starvation and thieving armies who stripped the land barer than a plague of locusts. Lydia had seen such faces over and over again; so many times they marched as skulls through her dreams and made her jerk awake in the middle of the night. So now she didn’t look at the faces.

With a quick check to see that the Yeomans were too busy with the stew and the yams to notice, she added an extra spoonful to the woman’s wooden bowl. The woman’s silent tears of gratitude just made her feel worse.

And then she saw him. Standing apart from the others, a lithe and vibrant creature in the midst of this room of death and despair. He was too proud to come begging.

He was waiting for her when she came out. She knew he would be. His back was toward her as he stood staring out at the small graveyard that lay behind the church, and yet he seemed to sense the moment she was there because he said without turning his head, ‘How do the spirits of your dead find their way home?’

‘What?’

He turned, smiled at her, and bowed. So polite. So correct. Lydia felt a sharp spike of disappointment. He was putting a distance between them that hadn’t been there before, his mouth unsmiling, as though she were a stranger in the street. Surely she was more than that. Wasn’t she?

She lifted her chin and gave him the kind of cool smile that Mr Theo gave to Polly when he was being sarcastic.

‘You came,’ she said and glanced casually away at St Saviour’s bell tower.

‘Of course I came.’

Something in his voice made her look back. He’d moved closer, so silent she’d heard no footsteps, yet here he was, near enough to touch. And his long black eyes were talking to her, even though his mouth was silent. His face was turned slightly away, but his gaze was fixed on hers. She smiled at him, a real smile this time, and saw him blink in that slow way a cat does when the sunlight is too bright.

‘How are you?’ she asked.

‘I am well.’

But the look he gave her said otherwise, and as though he were perched on a cliff edge, his nerves seemed to tighten, his muscles tense under the thin black tunic. It was as if he were about to jump off. Then he gave a strange little sigh, and with no more than a flicker of a shy smile he turned his head. For the first time she saw the right side of it.

‘Your face…,’ she gasped, then stopped. She knew that the Chinese regarded personal comments as rude. ‘Is it painful?’

‘No,’ he said.

But he had to be lying. That side of his head was split and swollen. A livid black bruise, shot through with dried blood, ran along his hairline from his forehead down to his ear. The sight of it made Lydia furious.

‘That policeman,’ she said angrily. ‘I’ll report him for…’

‘Doing his duty?’ He did not smile this time, his black eyes serious. ‘I think it would not be wise.’

‘But you need treatment,’ Lydia insisted. ‘I’ll fetch Mrs Yeoman, she’ll know what to do.’ She swung back in the direction of the hall, in a hurry to bring help.

‘Please, no.’ His voice was soft but insistent.

She stopped, looked at him. Looked at him hard, this figure she knew and yet didn’t know. He stood very still. Holding something in. What? What more was he keeping from her? His stillness was as elegant as his movements had been in the alley, his shoulders muscular but his hips narrower than her own. Horrible black rubber shoes on his feet.

In the hall earlier, and even when he greeted her, she had not seen the damaged side of his face, and she realised now that he had kept it turned away from her. What if her reaction was all wrong in his eyes? To him it implied… what? That he was weak? Or unable to care for himself? She shook her head, knowing this was a strange and delicate world she was entering, as unfamiliar to her as his language. She had to tread carefully. She nodded to indicate acceptance of his wishes, then turned her face toward the tombstones, neat and orderly with carnations in little vases. This world she understood.

‘Their spirits go straight to heaven,’ she said with a gesture at the rectangles of grass. ‘It doesn’t matter where they die, if they are Christians, but if they’re wicked, they go to hell. That’s what the priests tell us, anyway.’ She glanced over at him. Instead of looking at the graves, he was watching her. She stared right back at him and said, ‘As for me, I’ll be going straight to hell.’ And she laughed.

For a moment he looked shocked, and then he gave her his shy smile. ‘You are mocking me, I think.’

Oh God, she’d got it wrong again. How do you talk to someone so different? In all her life in Junchow the only Chinese people she’d ever spoken to were shopkeepers and servants, but conversations like ‘How much?’ and ‘A pound of soybeans, please,’ didn’t really count. Her dealings with Mr Liu at the pawnshop were the nearest she’d come to communicating properly with a Chinese native, and even those were spiced with danger. She must start again.

Very formally, hands together and eyes on the ground, she gave a little bow. ‘No, I’m not mocking you. I wish to thank you. You saved me in the alleyway and I am grateful. I owe you thanks.’

He did not move, not a muscle shifted in his face or his body, but something changed somewhere deep inside him and she could see it. Though she didn’t know exactly what it was. Just that it was as if a closed place had opened, and she felt a warmth flow from him that took her by surprise.

‘No,’ he said, eyes fixed intently on hers. ‘You do not owe me your thanks.’ He came one step closer to her, so close she could see tiny secret flecks of purple in his eyes. ‘They would have cut your throat when they were done with you. You owe me your life.’

‘My life is my own. It belongs to no one but me.’

‘And I owe you mine. Without you I would be dead. A bullet would be in my head now if you had not come out of the night when you did.’ He bowed once more, very low this time. ‘I owe you my life.’

‘Then we’re even.’ She laughed, uncertain how serious this was meant to be. ‘A life for a life.’

He looked at her, but she couldn’t fathom the emotion in his eyes this time, it was so still and dark. He said nothing and she wasn’t sure how much he’d understood, especially when he asked, ‘Does your Mrs Yeoman own a needle and thread?’

‘Oh, I expect so. Do you want me to fetch it?’

‘Yes, please. It would be kind.’

Her eyes scanned his clothes, a V-necked tunic and loose trousers, but could see no holes in them, so maybe it was for some sort of blood-brother ritual, to sew their lives together. The idea sent a flare of heat racing up her spine, and for the first time since she’d been herded into the concert room last night by Commissioner Lacock himself, the tight ball inside her lungs loosened and she could breathe.

10

‘My name is Lydia Ivanova.’

She held out a hand to him and he knew what she was expecting. He’d seen them do it, the foreigners. Seizing each other’s hands in greeting. A disgusting habit. No self-respecting Chinese would be so rude as to touch another, especially someone he didn’t know. Who would want to hold a hand that may have just come from gutting a pig or stroking a wife’s private parts? Barbarians were such filthy creatures.

Yet the sight of her small hand, pale as a lily and waiting for him, was curiously inviting. He wanted to touch it. To learn the feel of it.

He shook hands. ‘I am called Chang An Lo.’

It was like holding a bird in his hand, warm and soft. With one squeeze he could have crushed its fragile bones. But he didn’t want to. He experienced an unfamiliar need to protect this wild fluttering little creature in his hand.

She withdrew it as easily as she had given it and looked around her. He had led her out of the settlement along the back of the American sector and down a dirt track out to Lizard Creek, a small wooded inlet to the west of town. Here the morning sun lazed on the surface of the water and the birch trees offered dappled shade to the flat grey rocks. Lizards flicked and flashed over them like leaves in a breeze. Beyond the creek the land stretched flat and boggy after last night’s rain all the way north to the distant mountains. They shimmered blue in the summer heat, but Chang knew that somewhere hidden deep within the crouching tiger was a Red heart that was beating stronger every day. One day soon it would flood the country with its blood.

‘This place is beautiful,’ the fox girl said. ‘I had no idea it existed.’

She was smiling. She was pleased. And that created a strange contentment in his chest. He watched the way she dipped a hand into the gently flowing creek and laughed at a swallow that flashed its wings as it skimmed the water. Insects hummed in the heat and two crickets bickered somewhere in the reeds.

‘I come here because the water is clean,’ he explained to her. ‘See how clear it is, it lives and sings. Look at that fish.’ A silver swirl and it was gone. ‘But when this water joins the great Peiho River, the spirits leave it.’

‘Why?’ She sounded puzzled. Did she know so little?

‘Because it fills up with black oil from the foreigners’ gunboats and poisons from their factories. The spirits would die in the brown filth of the Peiho.’

She gave him a look but said nothing, just sat down on a rock and tossed a stone into the shallows. She stretched out her legs, bare and slender, toward the water and he noticed a hole in the bottom of one of her shoes. The fiery hair was hidden away under a straw hat, and he was sorry for that. The hat looked old, battered, like her shoes. Her hair always looked new and he wanted to see its flames again. She was watching a small brown bird tugging at a grub in a dead branch at her feet.

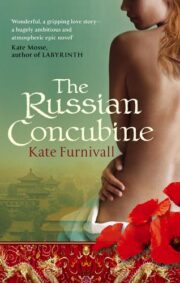

"The Russian Concubine" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "The Russian Concubine". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "The Russian Concubine" друзьям в соцсетях.