‘Now will you say yes?’ Theo demanded.

Her black eyes were bright with happiness. ‘Ask me again.’ ‘Will you marry me, Li Mei?’

‘Yes.’

‘Tiyo.’

‘What is it?’

‘She’s there again. At the gate.’

‘Who?’

‘The Chinese woman.’

‘Ignore her.’

‘Perhaps she wants her cat back.’

‘You mean Yeewai?’

‘Yes. The creature used to be hers. And now you say her husband has been executed and his boat taken, as well as her daughter, there’s no reason why you couldn’t give the animal back to…’

‘If she wants the cat, let her ask.’

‘I don’t like the woman, Tiyo. Or her cat. There are bad spirits around her head.’

‘Superstitious claptrap, my love. There’s no harm in her. But if it’ll please you, I’ll give her a few dollars next time I go out.’

‘Yes, do that, Tiyo. It might help.’

But when Theo drove out, there was no sign of Yeewai’s previous owner and he gave her no thought. The traffic across town was slow, the streets full of Saturday shoppers, so it took him longer than he expected to reach Alfred’s house and he was annoyed at being late. In the days that were to follow, he would go over these moments again and again in his mind, trying to get them straight and in the right order, to see if anything could have been done differently. But some were fuzzy and indistinct. His arrival was one of those. He remembered backing the Morris Cowley into the drive and leaving it near the open gates because Alfred’s big Armstrong Siddeley was already taking up most of the space. But after that, nothing until Alfred was clapping him on the shoulder.

‘Good to see you, old chap. I know Lydia is longing to thank you.’

It didn’t look like that to Theo. She was standing by the window in the drawing room, holding herself very stiffly. Either the girl was in pain or she was on guard. Could be both. Theo followed her line of sight to see what she was staring at outside. Nothing. Just an old garden shed. She didn’t look well. Gaunt cheeked. Her skin transparent. Her mouth was pulled tight with strain and her amber eyes seemed to have turned several shades darker. Yet something in them gleamed, as if there were a bright light deep down there, a kind of fire he had not seen in them before. He remembered that, when he conjured up her image later. That fire.

‘Lydia, come over and say hello to Mr Willoughby.’

It was Valentina who spoke. She was smiling enchantingly at Theo, and he got the feeling she was one or two ahead of him in the vodka chase. When he thought back later, it was her long cool throat he recalled, though he didn’t know exactly why. She was wearing something bright, red maybe, that showed off her creamy white throat with its delicate pulse throbbing at the base. She kept touching it with her scarlet-tipped finger. Her mouth smiled a lot. And her eyes were genuinely happy, so that she looked younger than at the wedding only a few weeks earlier.

‘We are so very lucky to have you home again, aren’t we, darling? Safe and sound. Well,’ she laughed and the look she gave her daughter flickered with something more fragile, ‘nearly sound anyway.’

‘How are you, Lydia?’ Theo asked.

‘I’m well now.’

‘Good for you, young lady.’

‘Come on, darling, don’t be so rude. Thank Mr Willoughby.’

‘Thank you, Mr Willoughby. For searching for me.’

‘Poof, what kind of words are those? He deserves better than that. He risked his life.’

Lydia shivered. Then she smiled and something seemed to open up in her, letting out a young eagerness for a moment. She offered him her hand.

‘I am grateful, Mr Willoughby, really I am.’

‘It’s your Russian bear you should be thanking. He was the one who did the dirty work.’

‘Liev,’ she said.

She raised the glass of lime juice in her hand and turned to where Liev Popkov was slumped in an armchair. He was peering with his one eye into the depths of a glass of vodka that was swallowed up in his great paw, but when he saw her look across he shook his black curls at her and showed his teeth. It made him look ready to take a bite out of someone. Valentina glared at him and muttered something under her breath in Russian.

‘And Chang An Lo?’ Theo asked.

‘He’s in prison.’

‘I’m so sorry, Lydia.’

‘So am I.’

She went over and stood beside the big Russian, her knee only an inch from his elbow, and went back to staring out the window. They didn’t speak, but Theo could sense the connection between those two. Odd that. He could sense Valentina’s disapproval too. Obviously the invitation to Popkov had not been her idea. She moved off in the direction of the vodka bottle.

‘Sounds like bad news for Chang,’ Theo said in an undertone to Alfred, who was looking particularly smart in a new charcoal suit. Valentina had worked wonders with the old chap.

‘I’m afraid so.’

‘Execution?’

‘Inevitable, it seems. Any day now.’

‘Poor Lydia.’

Alfred took out a large white handkerchief and wiped his mouth as if to scoop up the words. ‘It might be for the best in the long run.’ He shook his head unhappily. ‘If only she would find herself a nice young English boy at that school of yours.’

‘Why so glum, my sweet angel?’ Valentina said with a laugh.

She’d returned to slide an arm around her husband’s waist. Theo was amused that his friend managed to look so pleased, yet at the same time so embarrassed by Valentina’s open display of affection. But the way Alfred looked at her, so much love in one small smile, it haunted him afterward.

The next hour blurred in Theo’s mind. But he knew the reason for that. It was shock. At what followed. It acted like a glass of water spilled over a page of writing, smearing all the words and making them run into each other like tears. So quite how he found himself walking into the driveway behind Valentina, he wasn’t sure. Something to do with cigarettes. That was it.

‘Oh damn,’ she’d exclaimed. ‘I’m out of smokes.’

‘Here, try one of mine,’ Theo offered.

‘Good God, no. They smell lethal.’

So he’d offered to drive her to the shop that sold her foul little Russian cigarettes and she’d been delighted. She’d gone over to her daughter, spoken softly in her ear, stroked her hair, obviously explaining why she was skipping off. Lydia nodded but made a face. Not happy. But in the drive he’d opened the passenger door for Valentina, that much he did remember. And the kiss. Her soft lips on his cheek and the smell of her scent, the light touch of her hand on his chest. She was so happy it was infectious, so brimful of life. It bubbled out of her. Her daughter was safe from both Po Chu and Chang An Lo, while Alfred lay curled in the palm of her hand. What more could she want?

As Theo climbed into the driving seat he saw two things that surprised him. One was Lydia standing in the doorway of the house. He couldn’t imagine why she’d come to see them drive off. The other was the Chinese woman, the one who’d thrust the cat into his arms on the junk and who’d been hanging around his gates for the last two days. What the hell was she doing here? The foolish woman placed her stubby body directly in front of the car. He hooted the horn. Her broad face and narrow eyes twisted into an expression of hatred and she spat at the windshield.

‘Aah, this crazy town is full of mad creatures,’ Valentina complained, but she wasn’t alarmed. Nothing could dent her good humour today.

‘I’ll get rid of her.’ Theo jumped out, and that was when everything went wrong.

The woman swung back her arm and threw something under the car. He started to run at her, but she was already racing out of the drive at an astonishing pace. Theo put a spurt on and had made it as far as the gate when the world cracked right down the middle. He could think of no other explanation. The noise was like the roar of the devil. He was hurled across the road and felt his wrist snap as he landed. His ears seemed to implode. He couldn’t hear.

He dragged himself off the tarmac and looked behind him. The Morris Cowley was gone. In its place was a crater and a few grotesque pieces of twisted metal. Behind it Alfred’s Armstrong Siddeley was all hunched over as if it had been kicked in the teeth. Broken glass trickled down from the sky like razor-sharp rain. Ten yards away on the scorched lawn lay the tattered remains of Valentina’s body. Her flesh turned to raw meat. Lydia was kneeling beside it, her mouth open wide in a scream that Theo couldn’t hear, her hands cradling her mother’s shattered face.

It was then that shock shuffled the images in his head and sent him spinning down into a cold black pit.

62

The funeral was a ghastly affair. Theo almost didn’t go but knew he had to face it. He could have used his injuries as an excuse. Not deep injuries. But showy. Cuts and bruises on his face, a broken wrist in plaster. A strip of flesh missing from one ear. But he went. If it hadn’t been for him, there would be no need of a funeral and he was going to have to learn to live with that fact. He honestly couldn’t understand why Alfred and the Russian girl didn’t whip him out of the church. But they didn’t. Both wore severe black. And faces as grey as the earth that would soon swallow up Valentina. Theo took a place in the back pew, and beside him Li Mei sat with curious eyes and the white flower of mourning in her hair.

‘Dear friends, let us give thanks for the life of Valentina Parker, who was a joy to us all.’ Standing in the pulpit with a wide smile was the old missionary, the one who was at the wedding, with hair as white as Abraham’s. ‘She was one of our dear Lord’s bright lights that sparkle in this world. And He gave her the gift of music to delight us.’

Theo had no stomach to listen. He disliked churches. He didn’t like the intimidation woven so skilfully into their magnificent architecture, all designed to make you feel a worthless sinner. But if Valentina was really one of this awesome God’s bright lights, why extinguish her so brutally? Why make Alfred, who was one of God’s most devoted servants, suffer this agony? It made nonsense of the concept of a loving God. No, the Chinese knew better. Bad things happen because the spirits are angry. It made sense. You have to appease them, which was why Theo had decided to follow Chang’s advice and build a shrine in his house to the spirits of his father, his mother, and his brother. He would give them no excuse to harm his Li Mei the way they’d harmed Valentina. This was China. Different rules applied.

The Chinese boat woman with her grenade knew that. She had blamed him for the execution of her husband and for the suicide of her daughter in Feng Tu Hong’s bed, and ended by blowing herself up with a second grenade. But that didn’t mean she was no longer a threat. Theo had made Li Mei promise to speak kindly to the cat Yeewai in future, just in case. Spirits were unpredictable.

When the congregation rose to sing ‘Onward Christian Soldiers,’ Theo remained seated and closed his eyes. His hand held Li Mei’s tight.

The funeral reception was worse. But Theo was pleased to see Polly standing firmly beside Lydia the whole time, caring for her friend, warding off well-wishers. Alfred held himself together too well. It was heartbreaking to watch.

‘If I can help out in any way, Alfred…’

‘Thank you, Theo, but no.’

‘Dinner one evening?’

‘That’s kind. Not yet. Maybe later.’

‘Of course.’

‘Theo.’

‘Yes?’

‘I’m thinking of applying for a transfer. Can’t stay here. Not now.’

‘Understandable, my dear fellow. Where would you go?’

‘Home.’

‘England?’

‘That’s right. I’m not cut out for these heathen places.’

‘I’ll miss you. And our games of chess.’

‘You must come and visit.’

‘But what about the girl? What will you do with Lydia?’

‘I’ll take her with me. To England. Give her a good education. It’s what Valentina wanted.’

‘That’s quite a responsibility to shoulder. She knows nothing of England, don’t forget. And you can’t say she’s… well… tame enough. To fit in, I mean.’

Alfred removed his spectacles and polished them assiduously. ‘She’s my daughter now.’

Theo wondered whether the girl would see it like that.

‘I’m sorry, Alfred,’ he said awkwardly. ‘I can’t tell you how bad I feel that the hand grenade was meant for me. Not for Valentina.’

Alfred’s mouth went awry. ‘No, it’s not your fault, Theo, don’t blame yourself. It’s this damn country.’

But Theo did blame himself. He couldn’t help it. He chose to walk home instead of hopping into one of the rickshaws that clattered through the streets, though it would certainly have eased the aches in his legs. But he needed to walk. Had to stride out. To drive the demon of guilt from his soul.

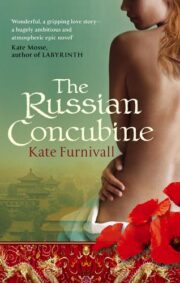

"The Russian Concubine" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "The Russian Concubine". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "The Russian Concubine" друзьям в соцсетях.