He was in no doubt that it would return time and again for years to come, and he would have to learn to find room for it in his heart. But in his clearer moments of mind he knew Alfred was right. It was this country. China had a history of thousands of years of violence, and even now its exquisite beauty was again being trampled underfoot in the stampede for power. They called it justice. A fight for equality and a basic wage. But really it was just another name for the same yoke around the necks of the people of China. They deserved better. It seemed to Theo that even the boat woman who threw the grenade deserved better. What kind of justice system served up freedom in exchange for your daughter’s young body in bed? Or sold children into slavery?

‘Willbee, you will put the other arm in plaster if you do not take more care.’

Theo jerked back from the road where a flurry of wheels was speeding past, a noisy never-ending stream of motorcars and bicycles, rickshaws and wheelbarrows. Even a boy on a scooter hooted a klaxon at him.

‘Good day to you, Feng Tu Hong.’

The black Rolls-Royce was murmuring at the kerbside with the rear window down, but the man inside was not the one who had radiated so much strength and power only days before. One look at Feng Tu Hong’s face and Theo saw the bewildered eyes of a father who has lost his son. He was wearing a white headband.

‘I have been searching for you, Willbee. Please, honour me with a moment of your time. A brief ride in my worthless motorcar might ease the burden of the wounds you bear.’

‘Thank you, Feng. I accept.’

They rode in silence at first, each man too full of his own thoughts to find the words to form a bridge. The streets were thronged with people going about their business in the bright winter sunshine, but the car attracted attention as it passed and several Chinese men lowered their foreheads to the pavement. Feng did not even notice.

‘Feng, I offer you sympathy for your loss. I am sorry I was not able to help the situation, but the farmhouse was already empty when I arrived.’

‘So I learned.’

‘Your daughter also sends her father sympathy for his sorrow.’

‘A dutiful daughter would be at my side.’

‘A dutiful father would not threaten his daughter so savagely.’

Feng refused to look at Theo but stared straight ahead in his own black world, his broad chest expanding as he took a deep breath to hold hard on his temper. It suddenly dawned on Theo that this man wanted something. It was not hard to guess what.

‘Feng Tu Hong, you and I have a history of discord and it saddens me that we cannot put aside our differences for the sake of your daughter whom we both love. At a time like this when you are overflowing with grief for your last son…,’ he lingered on those final two words, ‘… I invite you to my home.’

He heard the big man’s sharp intake of breath.

‘Your daughter will be honoured to serve you tea, though what we offer is meagre compared to your own lavish table. But at this moment of sadness, Feng, there must be no raised voices.’

Feng turned slowly. His bull neck hunched defensively. ‘I thank you, Willbee. It would please my heart to set eyes once more on my daughter. She is my only child now and I wish to cause her no distress.’

‘Then you are welcome.’

Feng leaned forward, pushed the glass partition aside, and gave his driver new instructions. When he slid the glass back into place, he shifted uneasily on the leather seat and gave a deep cough in the back of his throat, preparing himself.

Theo waited. Wary.

‘Tiyo Willbee, I have no son.’

Theo nodded but remained silent.

‘I need a grandson.’

Theo smiled. So that was it. The old devil was begging. It changed everything. Li Mei now held the power.

‘Come,’ Theo said courteously as the car pulled into the Willoughby Academy’s courtyard. ‘Drink tea with us.’

It was a start.

63

‘Lydia!’

Lydia was in her bedroom. She had been staring out at blackness and rain. In a chasm of loneliness for so many hours, her mind had escaped the present. She was way back on a day when her mother had danced into the attic with a small square loaf of something she called malt bread in one hand and a whole block of bright yellow butter in the other. Lydia had been so excited by the strange new smell and squidgy texture of the loaf that didn’t look a bit like bread, she had scrambled up on a chair to watch as Valentina spread great wedges of the butter on the bread. Then Valentina had fed the fruity slices piece by piece into Lydia’s open mouth. Exactly as if she were a baby bird. They had laughed so hard they cried. And now it twisted something inside her as she recalled how her mother had eaten so little of their meal herself, but licked the last scraps of butter off the knife and rolled her eyes in delicious ecstasy.

‘Lydia! Come quickly.’

Lydia’s instinct for danger was sharp. She snatched up a hairbrush as a weapon, raced onto the landing, and burst into Alfred’s bedroom. She stopped. For one unbearable moment hope reared up inside her. The room was full of people and they were all her mother. Alfred was sitting bolt upright on the edge of the double bed clutching two envelopes in one hand, the other hand twisted up in a hank of sheets as if trying to hang on to reality.

‘Lydia, look at these.’ His voice was breathless. ‘Letters.’

But Lydia couldn’t shift her gaze from the floor. Her mother’s clothes were spread out all over it, neatly arranged in matching sets.

Navy dress above navy shoes. Cream silk suit with camel blouse and tan sandals. Stockings, hats, gloves, even jewellery, placed as if she were wearing them. Empty bodies. Her mother there. But not there. A scarf each time where her face should be.

It was too much. She choked.

‘Lydia,’ Alfred said urgently, ‘Valentina has written to us.’ He wasn’t wearing his spectacles, and his face looked naked and vulnerable. Though the bedside clock showed four-twenty in the morning, he was still in yesterday’s rumpled suit, his jaw dark and in need of a shave.

‘What do you mean?’

‘I found them. Beneath her underwear in that drawer there. One for each of us.’ He abandoned the sheet and cupped the envelopes to his cheeks.

Lydia knelt down in front of him on the rug, placed her fingers lightly on his knees, and felt the shivers rippling through his body. She looked up into his face.

‘Alfred, Alfred,’ she murmured softly. Tears were flowing down his cheeks, but he was unaware of them. ‘We can’t bring her back.’

‘I know,’ he cried out. ‘But if God got His son back, why can’t I have my wife?’

My Darling Dochenka,

If you are reading this I have done the worst possible thing a mother can ever do to her child. Gone. Left you. But then I’ve never been good at doing the mother act, have I, sweetheart? It’s my wedding day today. I’m writing this because a horrible sense of foreboding has settled on me. Like a shroud. A coldness squeezes my heart. But I know that you’d laugh and toss your shining head at me and say it’s the vodka talking. Maybe it is. Maybe it isn’t.

So. I have some things to say. Important things. Chyort! You know me, darling. I don’t tell. I keep secrets. I hoard them like jewels and hug them to me. So I’ll say them quickly.

First, I love you, my golden daughter. More than my life. So if I’m already cold in the earth, don’t grieve. I’ll be happy. Because you are surviving and that’s what counts. Anyway I was never much good at life. I expect to find that the Devil and I get along just fine. And for hell’s sake, don’t cry. It’ll ruin your pretty eyes.

Now the hard part. I don’t know where to start, so I’ll just spit it out.

Your father, Jens Friis, is alive. There. It’s said.

He’s in one of Stalin’s hateful forced labour prisons in some godforsaken hellhole in Russia. Ten years he’s been there. Can you imagine it? How do I know? Liev Popkov. He came and told me the day you arrived home and found him with me in our miserable attic. That was also the day I’d said yes to Alfred’s proposal of marriage. Ironic? Ha! I wanted to die, Lydia, just die of grief. But what good could your father be to you, stuck out somewhere on the frozen steppes of Siberia and probably going to die sometime soon? None of them live forever in those barbaric death camps.

So I got you a new father. Is that so bad? I got you one who would look out for you properly. And for me. Don’t forget me. I was tired of being… empty. Thin and empty. I want so much more for you.

There. That’s said. Don’t be angry that I didn’t tell you sooner.

Now. A secret I never planned to tell. The words stick in my throat. Even now I could take this one to my grave with me. Shall I?

All right, darling, all right. I can hear you shouting at me though the worms are in my ears. You want the truth. Very well. I give you the truth, my little alley cat, but it’ll do you no good.

I’ve told you before that when I first saw your father, he was like a glorious Viking warrior, his heart beating so strong I could hear it across the room as I played the piano for Tsar Nicholas. Ten years older than I, but I swore to myself there and then that I would marry this Norse god. It took me three years, but I did it. However, nothing in life is simple, and when I was too young and silly for him to look twice at me, he had been busy at the tsar’s court in the Alexander Palace at Tsarskoe Selo. Now this is the scorpion’s tail. He was busy having an affair. Oh yes, my Viking god was human after all. The affair was with that Russian bitch, Countess Natalia Serova, and she carried Jens’s child.

Yes. Alexei Serov is your half-brother.

Satisfied?

Even now it makes me weep, my tears blur his name. And the countess had the sense to get out of Russia before the Red storm broke over us, so she was able to take with her the child and her money and her jewels. And left her poor cuckolded husband Count Serov to die by the blade of a Bolshevik sabre.

Now you know. That is why I would not have that green-eyed bastard in my house. His eyes are his father’s eyes.

There, dochenka. I am confessed. Do what you will with my secrets. I beg you to forget them. Forget Russia and Russians. Become my dear Alfred’s proper little English miss. It is the only way forward for you. So adieu, my precious daughter. Remember my wishes – an English education, a career of your own, never to be owned by any man.

Don’t forget me.

Poof, to hell with this craziness. I refuse to die yet, so this letter will grow old and yellow wrapped up in my best pair of silk French underwear. You will never know.

I want to kiss you, darling.

So much love,

from your Mama

Mama, Mama, Mama.

A torrent of emotions hit her. She hid herself in her room and shook so hard the paper quivered in her hand, but she couldn’t stop herself crowing with delight.

Papa alive! Papa. Alive. And a brother. Right here in Junchow. Alexei. Oh Mama. You make me angry. Why didn’t you tell me? Why couldn’t we have shared it?

But she knew why. It was her mother’s warped idea of protecting her daughter. It was the survival instinct.

Mama, I know you think I’m wilful and headstrong, but I’d have listened to you. Really I would. You should have trusted me. Together we…

An image of her father leaped out of nowhere. It rose up and filled the inside of her skull. He was no longer tall, but hunched, gaunt, and white-haired. His feet in shackles and raw with festering sores. The Viking sheen she had always thought he carried so easily on his broad shoulders was gone. He was dirty all over. And cold. Shivering. She blinked, shocked. The image vanished. But in that moment before her eyelids closed, Jens Friis looked directly at her and smiled. It was the old smile, the one she remembered, the one part of him she still carried inside her.

‘Papa,’ she cried out.

By seven o’clock in the morning she’d built a shrine. A big one. In the drawing room. Alfred sat and watched her in mute stillness as she swept everything off the long walnut sideboard and draped it with her mother’s maroon and amber scarves. At each end she placed the tall candles from the dining room. In the centre, taking pride of place, she stood a photograph of Valentina. Laughing, with her head tilted to one side and an oiled-paper parasol in her hand to keep off the sun. A happy honeymoon snapshot. She looked so beautiful, fit to enchant the gods.

Possessions next. Lydia worked out what Valentina would need and positioned the items around her. Hairbrush and mirror, lipstick, compact and nail polish, her snakeskin handbag stuffed with money from Alfred’s wallet. Jewellery box, an absolute must. And right in front where Valentina could reach it easily, a crystal tumbler filled to the brim with Russian vodka.

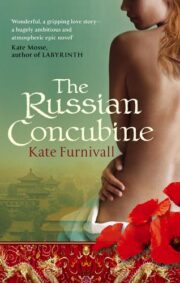

"The Russian Concubine" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "The Russian Concubine". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "The Russian Concubine" друзьям в соцсетях.