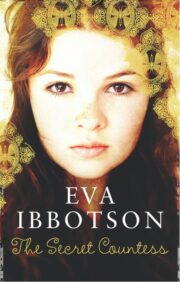

The Secret Countess

by

Eva Ibbotson

For Jane

The Author

Eva Ibbotson was born in Vienna, but when the Nazis came to power her family fled to England and she was sent to boarding school. She planned to become a physiologist, but hated doing experiments on animals and was rescued from some fierce rabbits by her husband-to-be. She became a writer while bringing up her four children, and her bestselling novels for both adults and children have been published around the world. Her books have also won and been shortlisted for many prizes. Journey to the River Sea won the Nestlé Gold Award and was runner-up for the Whitbread Children’s Book of the Year and the Guardian Fiction Award. The Star of Kazan won the Nestlé Silver Award and was shortlisted for the Carnegie Medal. Eva lives in Newcastle.

Books by Eva Ibbotson

A Song for Summer

The Star of Kazan

Journey to the River Sea

The Beasts of Clawstone Castle

The Great Ghost Rescue

Which Witch?

The Haunting of Hiram

Not Just a Witch

The Secret of Platform 13

Dial a Ghost

Monster Mission

Coming soon

The Morning Gift

PROLOGUE

In the fabled, glittering world that was St Petersburg before the First World War there lived, in an ice-blue palace overlooking the river Neva, a family on whom the gods seemed to have lavished their gifts with an almost comical abundance.

Count and Countess Grazinsky possessed — in addition to the eighty-roomed palace on the Admiralty Quay with its Tintorettos and Titians, its Scythian gold under glass in the library, its ballroom illuminated by a hundred Bohemian chandeliers — an estate in the Crimea, another on the Don and a hunting lodge in Poland which the countess, who was not of an enquiring turn of mind, had never even seen. The count, who was aide de camp to the tsar, also owned a paper mill in Finland, a coal mine in the Urals and an oil refinery in Sarkahan. His wife, a reluctant lady of the bedchamber to the tsarina, whom she detested, could count among her jewels the diamond and sapphire pendant which Potemkin had designed for Catherine the Great and had inherited, in her own right, shares in the Trans-Siberian Railway and a block of offices in Kiev. The countess’s dresses were made in Paris, her shoes in London and though she could presumably have put on her own stockings, she had never in her life been called upon to do so.

But the real treasure of the Grazinsky household with its winter garden rampant with hibiscus and passion flowers, its liveried footmen and scurrying maids, was a tiny, dark-haired, bird-thin little girl, their daughter, Anna. On this button-sized countess, with her dusky, duckling-feather hair, her look of being about to devour life in all its glory like a ravenous fledgling, her adoring father showered the diminutives which come so readily to Russian lips: ‘Little Soul’, of course, ‘Doushenka’, loveliest of endearments but, more often, ‘Little Candle’ or ‘Little Star’, paying tribute to a strange, incandescent quality in this child who so totally lacked her mother’s blonde, voluptuous beauty and her father’s traditional good looks.

Like most members of the St Petersburg nobility, the Grazinskys were cultured, cosmopolitan and multilingual. The count and countess spoke French to each other. Russian was for servants, children and the act of love; English and German they used only when it was unavoidable. By the time she was five years old, Anna had had three governesses: Madame Leblanc, who combined the face of a Notre Dame gargoyle with a most beautiful speaking voice, Fräulein Schneider, a devout and placid Lutheran from Hamburg — and Miss Winifred Pinfold from Putney, London.

It was the last of these, a gaunt and angular spinster with whose nose one could have cut cheese, that Anna inexplicably chose to worship, enduring at the hands of the Englishwoman not only the cold baths and scrubbings with Pears soap and the wrenching open of the sealed bedroom windows, but that ultimate martyrdom, the afternoon walk.

‘Very bracing,’ Miss Pinfold would comment, steering the tiny, fur-trussed countess, rigid in her three layers of cashmere, her padded capok lining, her sable coat and felt valenki along the icy quays and gigantic squares of the city which Peter the Great had chosen to raise from the salt marshes and swamp-infested islands of the Gulf of Finland in the worst climate in the world.

‘Not at all like the dear Thames,’ Miss Pinfold would remark, watching a party of Lapps encamped on the solid white wastes of the Neva — and receiving, on the scimitar of her crimsoned nose, a shower of snow from an overhanging caryatid.

It was during these Siberian walks that Anna would meet other children who shared her exalted martyrdom: pint-sized princelings, diminutive countesses, muffled bankers’ daughters clinging like clumps of moss to the granite boulders of their English governesses. Her adored Cousin Sergei, for example, three years older than Anna, his face between the earmuffs of his shapka, pale with impending frostbite and outraged manhood as he trudged behind his intrepid Miss King along the interminable, blood-red facade of the Winter Palace; or the blue-eyed, dimpled Kira Satayev, hardly bigger than the ermine muff in which she tried to warm her puffball of a nose.

Yet it was during those arctic afternoon excursions that Anna, piecing together the few remarks that the wind-buffeted Miss Pinfold allowed herself, became possessed of a country of little, sun-lit fields and parks that were for ever green. A patchwork country, flower-filled and gentle, in which a smiling queen stood on street corners bestowing roses which miraculously grew on pins upon a grateful populace… A country without winter or anarchists whose name was England.

Anna grew and nothing was too good for her. When she was seven her father gave her, on her nameday, a white and golden boat with a tasselled crimson canopy in which four liveried oarsmen rowed her on picnics to the islands. Each Christmas, one of Fabergé’s craftsmen fashioned for her an exquisite beast so small that she could palm it in her muff: a springing leopard of lapis lazuli, a jade gazelle with shining ruby eyes… To draw her sledge through the park of Grazbaya, their estate on the Don, the count conjured up two silken-haired Siberian yaks.

‘You spoil her,’ said Miss Pinfold, worrying, to the count.

‘I may spoil her,’ the tall, blond-bearded count would reply, ‘but is she spoilt?’

And the strange thing was that Anna wasn’t. The little girl, wobbling on a pile of cushions on the fully-extended piano stool to practise her études, gyrating obediently with her Cousin Sergei to the beat of a polonaise at dancing class or reciting Les Malheurs de Sophy to Mademoiselle Leblanc, showed no sign whatsoever of selfishness or pride. It was as though her mother’s cosseting, the fussing of the servants, her father’s limitless adoration, produced in her only a kind of surprised humility. Miss Pinfold, watching her charge hawk-eyed, had to admit herself defeated. If ever there was such a thing as natural goodness it existed in this child.

"The Secret Countess" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "The Secret Countess". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "The Secret Countess" друзьям в соцсетях.