Nonetheless, while Eloise and I are far from the same person, we occupy very similar worlds. Making Eloise a graduate student in the Harvard history department was a sop to all those years of English teachers who sternly admonished me to write what you know. I hated that advice. I didn’t want to write what I knew; I wanted to write about dashing men in knee breeches dangling improbably from ropes, conducting daring midnight escapes. But, despite all my fuming and fidgeting, I have to admit the wisdom of their advice. Placing Eloise in the same academic program and lending her my basement flat in Bayswater made her much easier to write about. I could picture her route to the British Library every morning, the kebab shop where she buys her fish and chips, even the clothes hanging in her closet. Even the party where Eloise attacks Colin with a Glo-Stick has a basis in a similarly bizarre bash I attended while overseas. There’s a certain nostalgic pleasure to revisiting my old haunts through Eloise’s eyes.

Q. The Secret History of the Pink Carnation borrows elements from a number of different genres. While the debt to Baroness Orczy is clear, which other authors influenced you in your work?

A. Cursed with literary schizophrenia, I grew up reading mysteries, romances, suspense, fantasy, spy novels, nineteenth-century fiction, and those wonderful multigenerational historical epics that proliferated through bookstore shelves back in the eighties. My father had a taste for historical fiction, and my mother for Japanese and Russian literature of the more lugubrious sort, so we had very eclectic bookshelves. I read anything, anywhere, at any time (although reading while roller-skating was not one of my better ideas). I’ve been staggering between genres ever since.

If I had to narrow it down to a crucial few, I would say that my imagination was molded by a combination of Alexandre Dumas, Margaret Mitchell, and Judith McNaught. I dashed down narrow alleyways with d’Artagnan, ran blockades with Rhett Butler, and exchanged quips with supercilious heroes in Regency ballrooms. But my stylistic sensibilities were shaped in the school of L. M. Montgomery, Nancy Mitford, and Elizabeth Peters, who, despite writing in completely different genres, all have a knack for an ironic turn of phrase and a winning way of highlighting life’s absurdities. When Judith Merkle Riley’s A Vision of Light came out, followed by Diana Gabaldon’s Outlander, it was the best possible combination of both tendencies: vivid historical scenes presented with a wry twist.

Q. What was the most difficult or frustrating part of the writing process?

A. It’s hard to pick just one. I’d have to go with those days when I sit down at the computer, and no one’s there. My characters are all out to lunch. Even the villain can’t be rousted out of his bed to do anything dastardly. I sit and scowl at the screen, drink ludicrous amounts of tea, check e-mail every three minutes, and generally work myself into a snit. The English language becomes an unfamiliar wilderness and words, with all the recalcitrance of a herd of stubborn sheep, refuse to allow themselves to be arranged into any semblance of coherence. And then, on the flip side, there are those days when the characters are jumping up and down in my head, shouting, “Pay attention to me!” and fluid lines of perfect prose are unrolling through my head—but I can’t act on any of it, because there’s something else I have to do, like grade student papers, or it’s four in the morning and I’ve already turned my computer off. Having learned from past experience that such moments are fleeting, I try to always keep paper and pen somewhere in the vicinity so I can catch at least a fraction of those fragments of narrative and dialogue before they scuttle away again. Of course, those instances—both sets of them—are more than outweighed by those glorious moments when the characters frolic across the page, doing all sorts of wonderful things I never expected them to do.

Q. Will Eloise and Colin’s story continue into the next book?

A. Although Eloise and Colin’s story continues, the next book, The Masque of the Black Tulip, belongs to Henrietta Selwick and Miles Dorrington, the Purple Gentian’s little sister and best friend. When Eloise follows Colin back to Selwick Hall to plunder the family archives, she discovers that there’s a new French spy on the loose: the Black Tulip. (My apologies to Alexandre Dumas for stealing the name!) The Black Tulip is under orders to find and eliminate the Pink Carnation—which means, naturally, that someone will have to find and eliminate the Black Tulip. And who better to do so than Miles? Of course, Henrietta, the girl whose earliest words were “me, too!” insists on pursuing her own investigations. As I was writing The Secret History of the Pink Carnation, it became gloriously clear that Henrietta and Miles were perfectly suited—and equally clear that they were sure to fight it every step of the way. I’m happy to say they have proved me right on both counts.

Q. When will Jane get her own book?

A. I’m not sure how much I should give away . . . but the short answer to that is, not for a while yet. One of the constraints of working in the early nineteenth century is that heroines tend to marry young, much younger than suits our modern sensibilities. If they don’t, the author is forced to engage in alarming contortions to explain why the heroine has been left on the shelf for so long—forced to take care of the family estates, without the money to afford a Season, kidnapped by bandits and locked in a box till after she turned twenty-one, and so on. An interesting trend recently has been to have older, widowed heroines, where the age problem is dealt with by the expedient of an earlier marriage and a conveniently deceased husband. With Jane, however, this problem is moot. Jane has a wonderful reason for not marrying young: she’s too busy saving civilization from the depredations of Napoleon’s armies. I will say, however, that Jane does get her romance eventually, and I know exactly who it is—but that’s between me and Jane.

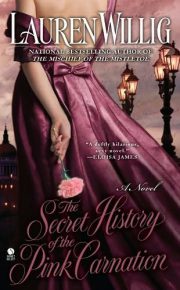

"The Secret History of the Pink Carnation" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "The Secret History of the Pink Carnation". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "The Secret History of the Pink Carnation" друзьям в соцсетях.