I was going to England and it was much against my will. I had argued persistently with Stirling.

“What good will it do?” I kept asking; and he set his lips stubbornly together and said: Tm going. It was his wish. “

“It was different when he was alive,” I insisted.

“I never agreed with his ideas but they had some meaning then.”

It was no use trying to reason with Stirling; and ia a way I was glad of this controversy because it took our minds from the terrible searing sorrow which we were both experiencing. When I was arguing with Stirling I was not thinking of Lynx lying on the brown earth, of their carrying his body home on the improvised stretcher; and I had to stop myself thinking of that I knew it was the same with Stirling.

There was something else we both knew. There was no comfort for either of us but in each other.

We should have turned to Adelaide. Her sound good sense would have served us well. She said she would not leave home; she was going to stay and keep things going for when we came back.

I wanted to stay, yet I wanted to go. I wanted to get right away from the house I had called Little Whiteladies. There were too many memories there; and yet I took a fierce and morbid delight in remembering every interview with Lynx, every game of chess we had played. But perhaps what decided me was that Stirling was going, and I had to be with Stirling. My relationship with Stirling was something I could not quite understand. I saw it as through a misted glass. How often in the past had I thought of marrying Stirling and yet when Lynx had married me that had seemed inevitable; and Stirling had made no protest. I believed that he felt towards me as I did towards him; but for the mighty personality of Lynx we should have married and been content. So now I had to be with Stirling. He and I could only have lived through those desolate weeks which followed the death of Lynx because of the knowledge that it was a desolation shared, and we belonged together.

“I am going to England,” he said firmly.

“He would want me to.”

So I knew I must go too.

Jessica came gliding into my bedroom one late afternoon when I was busy with preparations.

“So you’re going,” she said.

“I knew you would. You kept saying you’d stay but I knew you’d go.”

I didn’t answer and she sat on the bed watching me.

“So he’s gone,” she went on.

“He died, just like any other mortal being. Who would have thought it could have happened to him? But has he gone, Nora? He’d break free of death, wouldn’t he, just as he broke free of captivity? Out he came on the convict ship, like all the others, a prisoner. Then within a few weeks he breaks the fetters.

Could he break the fetters of death? “

“What do you mean, Jessica?”

“Will he come back? Do you think he’ll come back, Nora?”

He’s dead,” I said.

“You were lucky. You lost him before you knew him.”

“I knew him well,” I retorted.

“I was closer to him than anyone.”

She narrowed her eyes.

“You didn’t get to know the bad man in him. He was bad, Nora. Bad! You’d have found out in time just as the others did. All bad men see themselves as greater than other people. They see the rest of us as counters to be moved about to please them. You were a counter, Nora-a pretty counter, a favourite one … for the time being. He cherished you, but you were a counter all the same.”

I said: “Look here, Jessica, I have a lot to do. Don’t think you can change my feelings towards him. I knew him as you never could.”

“I’ll leave you with your pleasant dreams. Nobody can prove them false now, can they? But he’ll come back. He’ll find some way to cheat death as he cheated others. He’s not gone. You can sense him here now. He’s watching us now, Nora. He’s laughing at me, because I’m trying to make you see the truth.”

“I wish you were right,” I said vehemently.

“I wish he would come back.”

“Don’t say that!” she cried fearfully, looking over her shoulder.

“If you wish too fiercely he might come.”

“Then I’ll wish it with all my heart.”

He wouldn’t come back as you knew him. He’s no longer flesh and blood.

But he’ll come back . just the same. “

I turned away from her and, shaking her head sadly, she went out. I buried my face in the clothes which I had laid out on the bed and I kept seeing hundreds of pictures of him: Lynx the master, a law unto himself; a man different from all others. And lifting my face I said:

“Lynx, are you there? Come back. I want to talk to you. I want to tell you that I hate your plans for revenge now as I always did. Come back.

But there was no sign—no sound in the quiet room.

Adelaide drove with us to Melbourne and we stayed a night at The Lynx; the next day she came aboard to say goodbye to us. I am sure Stirling was as thankful as I was for precise Adelaide, who kissed us affectionately and repeated that she would keep the home going until we returned. So calm, so prosaic, I wondered then whether she was like her mother for she bore no resemblance to Lynx. As our ship slipped away she stood on the quay waving to us. There were no tears. She might have been seeing us off for a trip to Sydney.

I remembered sailing from England on the Carron Star. How different I was from that girl! Since then I had known Lynx. The inexperienced young girl had become a rich widow—outwardly poised, a woman of the world.

Stirling stood beside me as he had on that other occasion; and I felt comforted.

Turning, I smiled at him and I knew he felt the same.

We went first to the Falcon Inn. How strange it was to sit in that lounge where I had first met Stirling and pour the tea, which had been brought to us, and hand him the plate of scones. He was aware of it too. I knew by the way he smiled at me.

“It seems years ago,” he said; and indeed it did. So much had happened. We ourselves had changed.

We had talked a great deal in the ship coming over. He was going to buy Whiteladies because, he said, the owners would be willing to sell.

They would, in fact, have no alternative. He would offer a big price for it—a price such as they could not possibly get elsewhere. What did it matter? He was the golden millionaire.

“You can’t be certain they’ll sell,” I insisted.

“They’ve got to sell, Nora,” was his answer.

“They’re bankrupt.”

I knew who had helped to make them so and I was ashamed. The triumvirate, he had called us when I had discovered the mine. I wished I were not part of this.

There were things they could do, I pointed out. They could take paying guests, for instance.

“They wouldn’t know how!” Stirling laughed and in that moment he was amazingly like Lynx.

My feelings were in a turmoil. I set myself against them. I felt there was something in what Jessica had said. Lynx was still with us. And I didn’t want those people to sell the house. I was on their side.

Stirling’s eyes looked like pieces of green glass glinting through his sun-made wrinkles. He was so like Lynx that my spirits rose and I was almost happy. Whatever I said, he would acquire Whiteladies. It would be as Lynx wanted it. The Herrick children would play on the lawns and in time be the proud owners; and those children would be mine and Stirling’s. I could almost hear Lynx’s voice: “That’s my girl Nora.”

And I thought of the lawn on which I had once sat uneasily and the house with its grey towers—ancient and imposing—and understood the desire to possess it.

“The first thing to do is to let it be known that we are looking for a house,” said Stirling.

“We have taken a fancy to the district and want to settle here for a while. We are particularly interested in antiquity and have a great fancy for a house such as Whiteladies. I have already mentioned this to the innkeeper.”

“You lose no time,” I said.

“Did you expect me to? I had quite a conversation with the fellow. He remembered our staying here before, or so he said. He tells me that Lady Cardew died and that Sir Hilary married the companion or whatever she was.” - “Her name was Lucie, I believe.”

He nodded at me, smiling.

“I thought she was very humble,” I went on.

“Not quite one of the family. That will be changed now, I daresay.”

“You’re very interested in them, Nora.”

“Aren’t you?”

“Considering we have come across the world to buy their house, I certainly am.”

“You arc too sure,” I told him.

“How can you know what price will be asked? “

He looked at me in astonishment. What does it matter? He was the golden millionaire. But sometimes a price is not asked in gold.

That very day we paid a visit to the local house agent, and learned that a temporary refuge could be found which seemed the ideal place while we were looking round. By a stroke of great good luck the Wakefields were letting the Mercer’s House—a pleasant place and ideal for our purpose while we searched. Only, he warned us, there was no house in the neighbourhood to be compared with Whiteladies except perhaps Wakefield Park itself—and even that was no Whiteladies. We said we were very interested in renting the Mercer’s House and made an appointment to see it the next day.

The house agent drove us over in his brougham where Mr. Franklyn Wakefield was waiting to receive us. I remembered him at once and a glance at Stirling showed that he did too.

He bowed to me first, then to Stirling. His manners seemed very formal but his smile was friendly.

“I hope you will like the Mercer’s House,” he said, ‘though you may find it a little old-fashioned. I have heard it called inconvenient.”

“I’m sure it won’t be,” I told him, secretly amused because the agent’s reports had been so glowing while it seemed that its owner was doing his best to denigrate it.

“In fact we are enchanted by it … from the outside, aren’t we, Stirling?”

Stirling said characteristically that it was in fact the inside of the house with which we must concern ourselves if we were going to live in it.

“Therefore,” said Mr. Wakefield, “I am sure you will wish to inspect it thoroughly.”

“We shall,” said Stirling, rather grimly, I thought; and I remembered that he had taken a dislike to Franklyn Wakefield from the first moment he had seen him.

I said quickly: “You understand we should only be taking the house temporarily?”

“I was cognizant of the fact,” said Mr. Wakefield with a smile.

“But I daresay that however short the time you will wish for the maximum of comfort.”

I looked at the house with its elegant architecture—Queen Anne, I guessed. Over the walls hung festoons of Virginia creeper and I imagined what a glorious sight it would be in the autumn. There were two lawns in front of the house one on either side of the path—trim and well kept. I felt the need to make up for Stirling’s boorishness by being as charming as possible to Mr. Wakefield.

“If the inside is half as delightful as the outside. I shall be enchanted,” I said. He looked pleased and I went on.

“Am I right in thinking it is Queen Anne or early Georgian?”

“It was built in 1717 by an ancestor of mine and has been in the family ever since. We’ve used it as a sort of Dower House for members of the family. At this time there is no one who could occupy it. That is why we thought it advisable to seek a tenant.”

“Houses need to be lived in,” I said.

“They’re a little sad when empty.”

Stirling gave an explosive laugh.

“Really, Nora! You’re giving bricks and mortars credit for feelings they don’t possess.”

“I think Mrs….”

“Herrick,” I supplied.

“I think Mrs. Herrick has a good point,” said Mr. Wakefield.

“Houses soon become unfit for human habitation if they remain unoccupied too long.”

“Well, we’d better look round,” said Stirling.

The house was elegantly furnished. I exclaimed with pleasure at the carved ceiling in the hall. -“That,” explained Mr. Wakefield, ‘is the Mercer’s coat of arms you see engraved on the ceiling. You will see it in many of the rooms. “

“Of course, it’s the Mercer’s House, isn’t it?”

We went into the drawing-room with its french windows opening on to a lawn.

“We should need at least two gardeners,” said Stirling as though determined to find fault with the place.

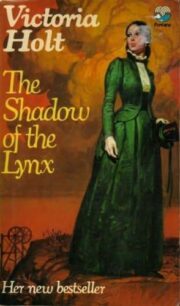

"The Shadow of the Lynx" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "The Shadow of the Lynx". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "The Shadow of the Lynx" друзьям в соцсетях.