Christmas had come and gone. The Christmas bazaar had been held in the newly restored hall of Whiteladies; Stirling had provided lavish entertainment free of charge, something which had never been done before. It was a great success and everyone enjoyed our new affluence.

We entertained the carol singers at Whiteladies and soup and wine and rich plum cake were served to them. I heard one of the elder members say that it was like old times and even then they hadn’t been treated to such good wine.

We had only a small dinner-party on Christmas Day because of our recent bereavement—just the family, with Nora and Franklyn; and on Boxing Day we all went to Wakefield Park.

The new year came and then I experienced the first of those alarming incidents.

That morning at breakfast Stirling was talking—as was often the case—about the work which was being done in the house.

They’ve started on the bartizan, he said.

“There’s more to be done up there than we thought at first.”

“Won’t it be wonderful when it’s all finished,” I cried.

“Then we can enjoy living in a house that is not constantly overrun by workmen.”

“Everything that has been done has been very necessary,” Stirling reminded me.

“If my ancestors can look down on what’s happening at Whiteladies, they’ll call you blessed.”

He was silent for a while and then he said: “A big house should be the home of a lot of people.” He turned to Lucie and said: “Don’t you agree?”

“I do,” she answered.

“And you were talking of leaving us,” I accused.

“We shan’t allow it.

Shall we, Stirling? “

“Minta could never manage without you,” said Stirling, and Lucie looked pleased, which made me happy.

“Then there’s Nora,” I went on.

“How I wish she would come here. It’s absurd … one person in the big Mercer’s House.”

“She’s considering leaving us,” said Stirling.

“We must certainly not allow that to happen.”

“How can we prevent it if she wants to go?” he asked quite coldly.

“She’s been saying she’s going for a long time, but still she stays. I think she has a reason for staying.”

“What reason?” He looked at me as though he disliked me, but I believed it was the thought of Nora’s going that he disliked. I shrugged my shoulders and he went on: “Go and have a look at what they’ve done to the bartizan some time. We mustn’t let the antiquity be destroyed. They’ll have to go very carefully with the restoration.”

He liked me to take an interest in the work that was being done so I said I would go that afternoon before dark (it was dark just after four at this time of the year). I shouldn’t have a chance in the morning as I’d promised to go and have morning coffee with Maud who was having a twelfth-night bazaar and was worried about refreshments.

That would take the whole of the morning, and Maud had asked me to stay for luncheon. Stirling didn’t seem to be listening. I looked at him wistfully; he was by no means a demonstrative husband. Sometimes I thought he made love in a perfunctory manner-as though it were a duty which had to be performed.

Of course I had always known that he was unusual. He had always stressed the fact that he had no fancy manners, for be had not been brought up in an English mansion like some people. He was referring to Franklyn. Sometimes I think: he positively disliked Franklyn and I wondered whether it was because he knew that Franklyn admired Nora and he didn’t think any man could replace his father.

He needn’t have worried, I was sure. If Franklyn was in love with Nora, Nora was as coldly aloof from him as I sometimes thought Stirling was from me. But I loved Stirling deeply and no matter how he felt about me I should go on loving him. There were occasions in the night when I would wake up depressed and say to myself: He married you for Whiteladies. And indeed his obsession with the house could have meant that that was true. But I didn’t believe it in my heart. It was just that he was not a man to show his feelings.

I came back from the vicarage at half past three. It was a cloudy day so that dusk seemed to be almost upon us. I remembered the bartizan, and as Stirling would very likely ask me that evening if I had been up to look at it, I decided I had better do so right away, for any lack of interest in the repairs on my part seemed to exasperate him.

The tower from which the bartizan projected was in the oldest part of the house. This was the original convent. It wasn’t used as living quarters but Stirling had all sorts of ideas for it. There was a spiral staircase which led up to the tower and a rope banister. In the old days we had rarely come here and when I had made my tour of inspection with Stirling it had been almost as unfamiliar to me as to him. Now there were splashes of whitewash on the stairs and signs that workmen had been there.

It was a long climb and half-way up I paused for breath. There was silence about me. What a gloomy part of the house this was! The staircase was broken by a landing and this led to a wide passage on either side of which were cells like alcoves.

As I stood on this landing I remembered an old legend I had heard as a child. A nun had thrown herself from the bartizan, so the story went.

She had sinned by breaking her vows and had taken her life as a way out of the world. Like all old houses, Whiteladies must have its ghost and what more apt than one of the white ladies? Now and then a white figure was supposed to be seen on the tower or in the bartizan.

After dark none of the servants would go to the tower or even pass it on their way to the road. We had never thought much about the story, but being alone in the tower brought it back to my mind. It was the sort of afternoon to inspire such thoughts—sombre, cloudy, with a hint of mist in the air. Perhaps I heard the light sound of a step on the stairs below me. Perhaps I sensed as one does a presence nearby. I wasn’t sure, but as I stood there, I felt suddenly cold as though some unknown terror was creeping up on me.

I turned away from the landing and started up the stairs. I would have a quick look and come down again. I must not let Stirling think I was not interested. I was breathless, for the stairs were very steep and I had started to hurry. Why hurry? There was ho need to . except that I wanted to be on my way down; I wanted to get away from this haunted tower.

I paused. Then I heard it. A footstep—slow and stealthy on the stair.

I listened. Silence. Imagination, I told myself. Or perhaps it was a workman. Or Stirling come to show me how they were getting on.

“Is anyone there?” I called.

Silence. A frightening silence. I thought to myself: I’m not atone in this tower. I am sure of it. Someone is dose . not far behind me.

Someone who doesn’t answer when I call.

Sometimes I think there is a. guardian angel who dogs our footsteps and warns us of danger. I felt then that I was being urged to watch, that danger was not far behind me.

I ran to the top of the tower. I stood there, leaning over the parapet, gripping the stone with my hands. I looked down below, far below and I thought: Someone is coming up the stairs. I shall be alone here with that person . alone on this tower.

Yes. It was coming. Stealthy footsteps. The creak of the door which led to the last steps. Three more of those steps and then . I stood there clinging to me stones, my heart thundering while I prayed for a miracle.

Then the miracle was there below me. Maud Mathers came into sight with her quick, rather ungainly stride.

I called: “Maud! Maud!’ She stopped and looked about her.

Oh God help me, I prayed. It’s coming dose. Maud was looking up.

“Minta! What are you doing up there?” Hers was the sort of voice which could be heard at the back of the hall when the village put on its miracle play.

“Just looking at the work that’s being done.”

“I’ve brought your gloves. You left them at the vicarage. I thought you might want them.”

I was laughing with relief. I turned and looked over my shoulder.

Nothing. Just nothing! I had experienced a moment of panic and Maud with her common sense had dispelled it.

“I’ll come right down,” I said.

“Wait for me, Maud. I’m coming now.”

I ran down those stairs and there was no sign of anyone. It was fancy, I told myself. The sort of thing that happens to women when they’re pregnant.

I didn’t think of that incident again until some time afterwards.

By the end of January I was certain that I was going to have a child.

Stirling was delighted—perhaps triumphant was the word—and that made me very happy. I realized then that he had become more withdrawn than ever. I began to see less of him. He was constantly with the workmen; he was also buying up land in the neighbourhood. I had the feeling that he wanted to outdo Franklyn in some way, which was ridiculous really because the Wakefields had been at the Park for about a hundred years and however much land Stirling acquired there couldn’t be a question of rivalry.

Lucie cosseted me and was excited about the baby. She wanted to talk about it all the time.

“It will be Druscilla’s niece or nephew. What a complicated household we are!”

I was very amused when I discovered that Bella, the little cat which Nora had given me, was going to have kittens. I had grown very fond of Bella. She was a most unusual cat and Nora assured me that Donna was the same. They followed us as dogs do; they were affectionate and liked nothing so much as to sit in our laps and be stroked. They would purr away and I always smiled when I was at Mercer’s to see Donna behave in exactly the same way as Bella did. And when I knew Bella was going to have kittens I couldn’t resist going over to tell Nora.

I was a little uneasy with Nora nowadays. I hadn’t felt like that before my marriage, but now there seemed a certain barrier between us which might have been of her erecting because it certainly wasn’t of mine.

She was in the greenhouse where she was trying to grow orchids and Donna was sitting on the bench watching her at her work.

“Nora, what do you think?” I cried.

“Bella’s going to have kittens.”

She turned to look at me and laughed and she was how I liked her to be—amused and friendly.

“What a coincidence!” she said.

“You mean … both of us.”

Nora nodded.

“Poor Donna will be piqued when she knows.”

At the mention of her name Donna mewed appreciatively and rubbed herself against Nora’s arm.

“So she’s stolen a march on you, eh?” said Nora to the cat. And to me.

“What will you do with them?”

“Keep one and find a home for the others. I think they’d like one at the vicarage.”

So we went in and Mrs. Glee served coffee in that rather truculent way of hers which amused Nora and was meant to show how much better things were done at Mercer’s that at Whiteladies.

“I’m giving a dinner-party next week,” said Nora.

“You must come, Minta.”

“I’m sure we should love to.”

“It’s going to be a rather special occasion.” She didn’t say what and I didn’t probe. I was sure it was no use in any case. Nora was the sort of person who could not be coaxed into saying what she did not want to.

While we were drinking coffee we heard the sounds of a horse’s hoofs on the stable cobbles.

“It’s Franklyn,” said Nora, looking out of the window.

“He calls in frequently. We enjoy a game of chess together. I think he’s rather lonely since his parents died.”

Franklyn came in looking very distinguished, I thought. I wondered whether there would be an announcement of their engagement and this was what the party was going to be for. One couldn’t tell from either of them. But Franklyn’s frequent visits to Mercer’s seemed significant. After all, I knew him very well and I was sure he was in love with Nora.

I really looked forward to the dinner-party. It seemed to me that it would be such a pleasant rounding off if Nora married Franklyn and we all lived happily ever after.

But on the night of the dinner-party I had a shock. There was no mention of an engagement. Instead Nora told us that this would be one of the last dinner-parties she would give because she had definitely decided to go back to Australia.

Bella was missing. We guessed of course that she had hidden herself away in order to have her kittens, but we had no idea where. Lucie said it was a habit cats had. I was rather worried because I thought she would need food, but, as Lucie said, we shouldn’t worry about her for she would know where to come when she wanted it.

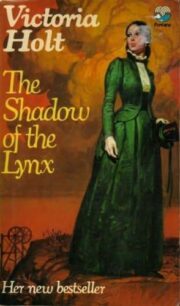

"The Shadow of the Lynx" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "The Shadow of the Lynx". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "The Shadow of the Lynx" друзьям в соцсетях.