“Please don’t talk of leaving us just as you have come. You’ll give it a fair trial, won’t you?”

“Of course. I was only thinking of what I should do if your father decided he didn’t want me here.”

“But he has promised to look after you and he will. Your father was insistent that he should.”

“My tamer seemed to tall under his spell.”

“They were drawn to each other from the start. Yet they were so different. Your father dreamed of what he would do; my father did it. In a short time they had become great friends; your father had come into the mine and managed it with an enthusiasm which we had never known before. My father used to say: “Now Tom Tamasin is here we’ll strike rich. He believes it so earnestly that it will come to pass.” And then he died bringing gold from the mine. “

“So they have found gold.”

“Not in any quantity. There is a lot of hard work; a lot of men to be employed; and the yield is hardly worth the effort and expense. It’s strange. In everything else my father has prospered. The property which came through my mother is worth ten times what it was when he took it over. This hotel which was just a primitive inn is now flourishing. As Melbourne grows so does the hotel with it. But I believe he loses money on the mine. He won’t give up, though. In his way he is as obsessed by the desire to find gold as those men you saw downstairs tonight.”

“Why do men feel this urge for gold?”

She shrugged her shoulders.

“As we were saying tonight, it is the thought of being rich, fabulously rich.”

“And your father … is he not rich?”

“Not in the way he wishes to be. He started years ago to search for gold. He’ll never give up the search until he makes a fortune.”

“I wonder people can’t be content if they have enough to make them secure, and then enjoy living.”

“You have a wise head on your shoulders. But you would never get some men to see it your way.”

“I thought your father was a wise man. Stirling talks of him as though he is Socrates, Plato, Hercules and Julius Caesar all rolled into one.”

“Stirling has talked too much. My father is just an unusual human being. He is autocratic because he is the centre of our world—but it is only a little world. Stand up to him. He’ll respect you for it. I understand you, I think. There is a little of your father in you, and you are proud and not going to bow to anyone’s will. I think you will be well equipped for your new country. I hope you will get along with Jessica.”

“Jessica? Stirling did not mention Jessica. Who is she?”

“A cousin of my mother’s. She was orphaned early and lived with my mother since their childhood. They were like sisters and when my mother died she was nearly demented. I had to comfort her and that helped me to get over my own grief. She can be rather difficult and she is a little strange. The fact is she never quite got over my mother’s death. She takes sudden likes and dislikes to people.”

“And you think she will dislike me?”

“One never knows. But whatever she does, always remember that she may at any time act a little strangely.”

“Do you mean that she is mad?”

“Oh dear me no. A little unbalanced. She will be quite placid for days. Then she helps in the house and is very good in the kitchen. She cooks very well when she is in the mood. We had a very good cook and her husband was a handyman-very useful about the place. They had a little cottage in the grounds. Then they caught the gold fever. They just walked out. Heaven knows where they are now. Probably regretting it in some tent town, sleeping rough and thinking of their comfortable bed in the cottage.”

“Perhaps they found gold.”

“If they had we should have heard. No. They’ll come creeping back but my father won’t have them. He was very angry when they left. It was one of the reasons I couldn’t come to England as was first planned.”

“Everyone there thought it was Miss Herrick who was coming for me.”

“And so it would have been, but my father couldn’t be left to the mercy of Jessica … so I stayed behind and Stirling came alone. Don’t imagine that we haven’t servants. There are plenty of them but none of the calibre of the Lambs. Some of them are aboriginals. They don’t live in the house and we can’t rely on them. They’re nomads by nature and suddenly they’ll wander off. One thing—you will never be lonely.

There are so many people involved in my father’s affairs. There’s Jacob Jagger who manages the property; William Gardner who is in charge of the mine; and Jack Bell who runs the hotel. You will probably meet him before we leave. They often come to see my father. Then there are people who are employed in these various places. “

“And your father governs them all.”

“He divides his attention between them, but it’s the mine that claims most of his attention.”

And there we were back to gold. She seemed to realize this, tor she was very sensitive.

“You’re tired,” she said.

“I’ll leave you now. We have to be up early in the morning.”

She came towards me as though to kiss me; then she seemed to change her mind. They were not, I had already teamed, a demonstrative family.

My feelings towards her were warm, and I believed she would be a great comfort to me in the new life.

Early next morning we boarded the coach, which seated nine passengers and was drawn by four horses. It appeared to be strong though light and well sprung, with a canopy over the top to afford some protection against the sun and weather. This was one of the well-known coaches of Cobb and Co. who had made travel so much easier over the unmade roads of the outback.

I sat between Adelaide and Stirling and we were very soon on our way.

Jack Bell, to whom I had been introduced before we left, stood at the door of the hotel to wave goodbye. He was a tall thin man who had failed in his search for gold and was clearly relieved to find himself in his present position. He was slightly obsequious to Stirling and Adelaide and curious about me; but I had seen too many of his kind the previous night to be specially interested in him.

Besides, the city demanded all my attention. I was delighted with it now that I could see it in daylight. I liked the long straight streets and the little trams drawn by horses; I caught a glimpse of greenery as we passed a park and for a time rode along by the Yarra Yarra river. But soon we had left the town behind. The roads were rough but the scenery magnificent. Above us towered the great eucalyptus reaching to the heavens, majestic and indifferent to those who walked below. Stirling talked to me enthusiastically of the country and it was easy to see that he loved it. He pointed out the red stringy barks the ash and native beech; he directed my attention to the tall grey trunks of the ghostly-looking gums. There were some, he told me, who really believed that the souls of departed men and women occupied the trunks of those trees and turned them grey-white. Some of the aboriginals wouldn’t pass a grove of ghost gums after dark. They believed that if they did they might disappear and that in the morning if anyone counted they would find another tree turned ghost. I was fascinated by those great trees which must have stood there for a hundred years or more—perhaps before Captain Cook sailed into Botany Bay or before the arrival of the First Fleet.

The wattle was in bloom and the haunting fragrance filled the air as its feather flowers swayed a little in the light breeze. Tree ferns were dwarfed by the giant eucalypts and the sun touched the smoke trees with its golden light. A flock of galahs had settled on a mound and they rose in a grey and pink cloud as the coach approached.

Rosellas gave their whistling call as we passed; and the beauty of the scene moved me so deeply that I felt elated by it. I could not feel apprehensive of what lay before me; I could only enjoy the beautiful morning.

It was the proud boast of the Cobb Coaching Company that horses were changed every ten miles, which ensured the earliest possible arrival.

But the roads were rough and clouds of dust enveloped us. I thought it was an adventurous drive but no one else seemed to share my opinion and it was taken for granted that there would be mishaps. Over hills and dales we went; over creeks with the water splashing the sides of the coach, over rocky and sandy surfaces, over deep potholes which more than once nearly overturned the coach. All the time our driver talked to the horses; he seemed to love them dearly for he used the most affectionate terms when addressing them, urging them to “Pull on faster, Bess me darling!” and “Steady, Buttercup, there’s a lady!” He was cheerful and courageous and laughed heartily when, having rocked over a hole in the narrow path with a sizeable drop the other side, we found ourselves still going.

Stirling was watching me intently as though almost hoping for some sign of dismay which I was determined not to show; and I gave no indication that travelling over the unmade roads of Australia seemed to me very different from sitting in a first-class carriage compartment going from Canterbury to London.

There was an occasion when one of the horses reared and the coach turned into the scrub. Then we had to get out and all the men worked together to get the coach back on to the road. But I could see that this was accepted as a normal occurrence.

We were delayed by this and spent the night at an inn which was very primitive. Adelaide and I shared a room with another traveller and there was no intimate conversation that night.

In the morning there was some difficulty about the harness and we were late starting. However, our spirits rose as we came out into the beautiful country and once more I smelt the wattle and watched the flight of brilliantly plum aged birds.

We were coming nearer and nearer to what I thought of as Lynx Territory and it was here that I had my first glimpse of what was called a tent town. To me there was something horribly depressing about it. The beautiful trees had been cut down and in their place was a collection of tents made of canvas and calico. I saw the smouldering fires on which the inhabitants boiled their billy cans and cooked their dampers. There were unkempt men and women, tanned to a dirty brown by sun and weather. I saw women, their hair tangled, helping with the panning or cradling, and turning the handles to bring up the buckets full of earth which might contain the precious gold; along the road were open-fronted shacks displaying flour, meat and the implements which would be needed by those concerned in the search for gold.

“Now you’re seeing a typical canvas town,” commented Stirling.

“There are many hereabouts. Lynx supplies the shops with their goods. It’s another trade of his.”

“So we are coming into the Lynx Empire.”

That amused Stirling. He liked to think of it as such.

The diggers’ children had run out to watch the coach as we galloped past. Some tried to run after it. I watched them as they fell behind and my heart was filled with pity for the children of the obsessed.

I was relieved when they were out of sight and I could feast my eyes on the dignified trees and watch for sleepy koalas nibbling the leaves which were the only ones they cared for, and now and then cry out with pleasure as a crimson-breasted rosella fluttered overhead.

It was dusk when we arrived.

The driver had gone a mile or so out of his way to drop us at the house. After all, we belonged to the Lynx household, which meant we must have special treatment. And as we stood there in the road before the house the grey towers of which made it look like a miniature mansion, I had the strange feeling that I had been there before. It was ridiculous. How could I have been? And yet the feeling persisted.

Two servants came running out. We had been long expected. One of them was dark-skinned; the other was named Jim.

“Take in all the baggage,” commanded Stirling.

“We’ll sort it out later. This is Miss Nora who has come to live with us.”

“Here we are,” said Stirling.

“Home.”

I walked with them to gates which were of wrought iron. Then I saw the name on them in white letters. It was “Whiteladies’.

Three

Whiteladies! The same name as that other house. How very strange! And stranger still that Stirling had not mentioned this. I turned to him and said: “But that was the name of the house near Canterbury.”

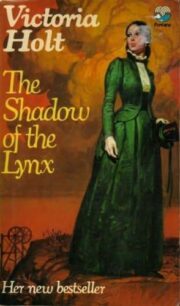

"The Shadow of the Lynx" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "The Shadow of the Lynx". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "The Shadow of the Lynx" друзьям в соцсетях.