Joelle took a sip of cool lemonade, then set the glass on the flat arm of the lounge chair. “I need to talk to you two,” she said, not completely sure she was ready to have this conversation.

Her parents turned in their chairs to face her.

“What’s up?” her father asked, reaching for a tortilla chip from the bowl on the table. He was wearing sunglasses, and she wished she could see his eyes.

“I’m pregnant,” Joelle said.

There was a moment of silence on the balcony.

“Oh, honey.” Her mother scraped her chair across the floor of the balcony to move it closer to the lounge. She put her hand on Joelle’s arm, her face impassive, unreadable, and Joelle felt some sympathy for her. Ellen didn’t know whether she should be happy for her daughter or not, and she was waiting for a cue from Joelle.

“It’s good and bad news,” Joelle said, “as you can probably guess.”

“How far along are you?” her father asked.

“Eighteen weeks,” she said. “Almost nineteen.”

“Wow,” said her mother. “You’re barely showing.”

“I haven’t emphasized it,” Joelle said. “I’ve tried to wear loose, nonmaternity clothes, but it will be impossible to hide soon. And, anyway, now everybody knows.”

“You poor thing,” said her mother. “You had to have your appendix out while you were pregnant!”

“Well, fortunately, everything turned out okay,” she said.

“Who’s the father?” her dad asked.

“That doesn’t matter,” her mother said quickly. “What matters is that you’re going to have a baby. Something you’ve wanted for so long. Something you thought was impossible.”

She imagined her mother was thinking the same thing as her colleagues—that she had gotten herself artificially inseminated or perhaps had found an egg donor. Something out of the ordinary, since everyone knew the struggle she and Rusty had had trying to conceive.

“I want you both to know the truth,” she said, longing to tell them. “But please keep this to yourselves.” Who would they tell, anyhow?

“Of course,” said her mother.

“Liam is the baby’s father.”

“Liam!” Her mother leaned back in the chair, surprise clear on her face. “I thought you and Liam were just friends.”

“We are.” She sighed and shook her head. “We spent so much time together when Mara got sick. And we became very close. One night…we made love. Just that one time, but…” She nodded toward her stomach. “That appears to have been enough.”

“Why does it have to be a secret?” her father asked.

Her mother turned to him. “Because Liam is married to Mara,” she explained as though he were senile. “He’s so committed to Mara. I’m actually surprised he would…” Her mother didn’t finish her sentence, but Joelle knew where she had been heading.

“But not surprised that I would?” she asked, then was instantly annoyed with herself. Her mother had meant nothing by her comment, and Joelle knew it. It was simply the truth. Anyone would be surprised that Liam had made love to another woman.

“That’s not what I’m saying,” her mother said.

“I know. It’s just…it’s a mess, Mom. We didn’t use birth control because neither of us figured I could get pregnant. And you’re right. Liam is completely and utterly committed to Mara.”

“Well, so are you,” her father said, rushing to her defense.

“What does Liam have to say about all this?” her mother asked.

Not much, she thought, feeling the unwelcome anger that had been teasing her lately. “He didn’t know until the appendectomy, when word finally got around that I was pregnant,” she said. “I was never going to tell him.” She smiled at them. “Actually, I was thinking of leaving here. Moving to Berkeley to be near you two, or to San Diego to be near another friend, where I could start a new life. Then no one here would have to know.”

Both of her parents stared at her in silence. “To spare Liam from having to deal with the whole thing,” her mother said. It was a statement rather than a question, and Joelle nodded.

“He’s so screwed up, Mom,” she said.

Her father shook his head. “You’ve always wanted to save everybody, Shanti,” he said. “Even when you were a kid, you’d take the blame for things the other kids did. Do you remember that?”

“Only once,” Joelle said, remembering the time she’d claimed she’d set fire to a flowering shrub near the cabin that served as the schoolhouse. She knew the parents of the boy who had actually set the fire would punish him far more severely than her parents would punish her.

“I can think of at least three or four times,” her father said.

“Are you still planning to move?” her mother asked.

Joelle shook her head. “No. There’s not much point to it now that the cat’s out of the bag. Liam and I are going to have to figure out how to handle this without creating more of a mess than we already have.” So far, though, Liam had shown little evidence that he planned to join her in that task.

While she was in the hospital, Liam had been careful to give her the attention befitting a friend with whom he’d worked for many years and about whom he cared a great deal, and nothing more than that. Paul treated her similarly. She doubted anyone’s suspicions had been raised. She wondered if, now that she was home, she would hear from Liam or if he would continue his policy of no longer calling her at night. Perhaps that would be wise. They would inevitably grow closer with each call, as they had before. She would love to have those calls again—she needed more support from him than she was getting—but that much contact could only lead them down the same slippery slope. “What do you want, honey?” Her mother touched her arm again. “What do you wish would happen?” There was such love in her mother’s eyes that Joelle had to look away from her.

She bit her lip. “I want what I can’t have,” she said, her voice breaking, and she began to cry.

“She’s tired,” her father said, talking about her as if she were not sitting just three feet from him.

“Dad’s right, hon.” Her mother leaned forward to stroke her hair. “How about a nap?”

Joelle nodded, letting her mother help her to her feet. She was tired. She reminded herself of Sam, when he’d gone too long without a nap and simply could not maintain his good disposition one minute longer.

She slept for hours, awakening to the unmistakable smell of her mother’s vegetable soup. Although her bedroom door was closed, the aroma still found its way to her bed, and it filled her with longing for her childhood, when everything had seemed so simple and good.

Slowly she got out of bed, her right side aching a bit. She combed her hair in the dresser mirror, thinking that she should tell her parents she’d finally gotten in touch with Carlynn Shire. They would love to hear that she and the healer were becoming friends, and that Carlynn would soon be working with Mara in earnest, for whatever that was worth.

Slipping on her sandals, she walked from her bedroom to the kitchen.

“That smells so good, Mom,” she said.

“I thought you might like some soup, even though it’s warm outside,” her mother said.

“You’re exactly right,” Joelle said, leaning against the breakfast bar. “My stomach still feels a bit queasy.”

Her father came up behind her and put his arm around her waist. “I’ve been thinking, Shanti,” he said. “Good and good and good can’t possibly equal bad.”

“What do you mean?” she asked him.

“You’re a good person,” he said. “And so is Liam, and so is Mara. There’s no way something bad can come from anything the three of you do.”

She was touched by his rationale, and she rested her head on his shoulder. “You’re so sweet, Daddy,” she said. “I’m glad you guys are here.”

Her father looked at her mother. “Hey,” he said, “remember Shanti’s cypress in Big Sur?”

“Yes, of course!” her mother said. “I’d forgotten all about that.” She looked at Joelle. “Do you remember? You’re supposed to take a cutting from it for each child you have. You know, plant a new tree for the new baby.”

She knew what they were talking about: the Monterey cypress planted on top of her placenta. To be honest, though, she didn’t recall anyone ever talking about taking a cutting from it to plant a tree for a new baby.

“I don’t have to bury the placenta under it, do I?” She tried to keep the teasing tone out of her voice, but wasn’t sure she had succeeded. She decided she would wait a while before admitting to them that she’d contacted the healer. She could only handle so much of her parents’ eccentricities at one time.

“No, of course not,” her father said. “We’ll go down and get you a cutting from it.”

“She really should get it herself,” her mother argued.

“You guys are too much.” Joelle laughed. “Is the soup ready yet?”

As she lay in bed that night, Joelle found herself thinking of Big Sur and the Cabrial Commune. It was more the smell of her mother’s vegetable soup than the discussion about the cypress that brought the memories to mind, and she felt a yearning to go back there, to the place she’d spent her first ten years of life. The troubles of the outside world had been nonexistent there, and the world inside the commune consisted only of friends and forest and fog. It was the place where her father and the midwife, Felicia, had taken the time to dig a hole and plant a cypress to ensure her future. She knew exactly where her cypress was planted—near the northwestern corner of the cabin that served as the schoolhouse. Each of the kids who’d been born at the commune knew which cypress was theirs, and all mysticism aside, it had been a pretty nice custom.

She’d been to the Big Sur area several times in the last twenty-four years, but never to Cabrial. Rusty had shown no interest in visiting the place where she’d grown up, and each time they drove down Highway One to Big Sur, she would pass the dirt road leading to the commune with an unspoken longing.

Maybe, after she had the baby, she would go.

26

San Francisco, 1959

“SHE’S MY RIGHT ARM,” LLOYD PETERSON SAID, HIS HAND ON Lisbeth’s shoulder. “I’m not sure if I can get along without her that long.”

He was looking across the reception desk at Gabriel, who had come to the office as they were closing up to plead with Lloyd to let Lisbeth take a vacation. Lisbeth had already told Gabriel she couldn’t possibly take a whole week away from the office in the middle of the summer, when she was the only girl working, but Gabriel was not one to give up easily.

“You need a break,” he’d told her as they walked back to his place from the cinema the night before. “You work too hard.” They’d just seen Some Like it Hot, during which Gabriel had whispered to her that he’d take her over Marilyn Monroe any day. Those flattering words were still on her mind as she listened to Lloyd and Gabriel’s amiable argument over the possibility of her taking some time off. He wanted to go to the coastal town of Mendocino with her for a week’s vacation. Although Lisbeth longed for a week alone with Gabriel, she knew Lloyd couldn’t spare her. Still she decided to let the two men—the two old friends and tennis partners—duke it out.

“Let’s talk about this over a beer,” Gabriel finally said to Lloyd, who nodded in agreement, and the two of them left her alone to close up the office.

Lisbeth had to smile as the men walked out the door. She doubted Gabriel would win this one, but it was sweet of him to try.

She turned on the radio on her desk, as she always did when she had the office to herself. Switching the station from Lloyd’s favorite, where the Kingston Trio was singing “Tom Dooley,” to the Negro station Gabriel had introduced her to, where the music was earthier and made her want to dance, she set about filing the charts that had been used that day.

Gabriel had become almost fanatical about wanting to take a vacation in Mendocino. He’d been talking about it ever since Alan and Carlynn honeymooned there after their wedding nearly two years earlier. They’d raved about the peace and quiet and the natural beauty of the location, saying how perfect it was for a romantic getaway. It would be different for her and Gabriel, though, Lisbeth knew. Whenever they stayed in a hotel, they had to get two separate rooms. Someday, Gabriel promised her, they would be married. She now wore a spectacular diamond and sapphire ring on her left hand, but they had not yet set a date. She trusted their relationship, its depth and its love, but she knew Gabe still harbored the fear that marriage to him would cost her more than he was worth.

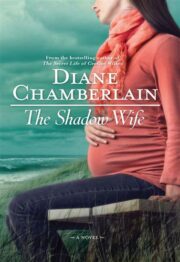

"The Shadow Wife" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "The Shadow Wife". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "The Shadow Wife" друзьям в соцсетях.