“Romeo and Juliet and all that. But how upsetting for you.”

“It was. If you had seen him, Cassie …”

“How I wish I had!”

“It was just horrible to think of that happening to him.”

“Because he was wearing Philip’s cloak. It might have happened to Philip.”

“Don’t speak of it.”

“You do love him, don’t you? I’m so glad. I love him too. This makes you really a part of the family.”

“Yes, I am very glad about it and so is Grand’mere.”

“So we are all happy.”

Julia came to the house accompanied by the Countess. The latter greeted me warmly, Julia less so. She looked at me with grudging admiration. Really, I thought, this capturing of a husband became an obsession with these girls because so much was made of their coming out. I was lucky. It hadn’t happened to me. My entrance into the world might have offended convention but it had given me Grand’mere and brought me to Philip. I must throw off the shadow Lorenzo’s death had cast over me; I must accept my happiness and rejoice in it.

Charles arrived at The Silk House. He and Philip were clo-setted together for a long while while Philip, as he said, caught up with what had been going on during his absence. One of the managers came down with a case full of papers and Philip decided that he would stay at The Silk House with the manager and Charles while he sorted them out.

We had been home only three days when Madalenna de’ Pucci arrived at the house. She came in a most unexpected manner.

We were dining. As Julia and the Countess were with us as well as Charles, we were a larger party than usual. On what she called “her good days” Lady Sallonger dined with us, and she was wheeled into the dining room. This was one of those occasions.

We were half way through the meal when one of the servants came in and announced that there had been an accident. A carriage had overturned right outside the house. The occupants were foreigners and it was not easy to understand what they were saying, but it seemed they were asking for help.

Lady Sallonger looked alarmed. “Oh dear … how tiresome,” she murmured. Charles said we had better go out and discover what it was all about.

In the hall stood a man. He was very dark and obviously harassed. He was talking at a great rate and in Italian.

We gathered that the carriage which he had been driving had overturned. His mistress, who was with her maid, had been hurt. He had been taking her to London.

Out in the road the carriage was lying on its side. The horses however were unharmed and standing patiently by. Seated on the roadside was a young woman; she was dark-haired and outstandingly beautiful. She was holding her ankle and appeared to be in some pain. Beside her sat a middle-aged woman who was wringing her hands and attempting to soothe her though the younger woman seemed calmer than she was.

Charles went to the young woman. “Are you in pain?” he asked.

“Si … si …” She lifted her beautiful eyes to his face appealingly.

“You must come into the house,” said Charles. I could see he was impressed by her beauty.

“Shall we see if you can stand on it?” said Charles. “If you can … I think that means no bones are broken.”

Philip said: “I’ll get some of the men from the stables to see what can be done about the carriage.”

The maid was talking volubly in Italian and the young woman got to her feet. She fell towards Charles who caught her.

“I think a doctor ought to see it,” I said.

“That’s the idea,” added Charles. “Send one of the servants for him. Let him explain what has happened.” He turned to the young woman. “Meanwhile you must come into the house.”

She leaned heavily on Charles who took her in, the maid running behind them talking all the time.

Some of the men had come out and were looking at the carriage. Philip remained with them while I went with Charles and the women into the house.

“Has the doctor been sent for?” asked Charles.

“Jim has gone off to fetch him,” Cassie told him.

“You are so kind …” said the Italian girl.

“Everything will be all right.” Charles spoke soothingly, caressingly.

Lady Sallonger, left in the dining room, was querulously asking what was going on. She called to me and I went in and told her.

“What is going to happen then?” she asked.

“I don’t know. They have sent for the doctor. She’s hurt her ankle and Charles thought it ought to be seen to.”

The doctor was soon with us. He examined the ankle and said he was certain no bones were broken. He thought it might be a strain. He must bind it up and he thought that a few days’ rest might put it to rights.

Charles said she must stay at The Silk House until she was fit to walk. Meanwhile Philip was discovering where the little party had come from and what their destination was. They were Italians—that we already knew—and they were visiting relations in England. The young lady, Madalenna de’ Pucci, had come from friends and was returning to her brother who was staying in London. They were going to return to Italy shortly.

A plan of action was decided on.

Charles insisted that she stay with us until her ankle was well. She protested weakly but Charles was adamant. She and Maria, the maid, should stay at the house. The carriage needed very little repairs and the men could do them immediately. The driver would take the carriage to London and explain to the brother what had happened, and in a few days Signorina Madalenna and her maid could return to London.

This plan was finally agreed on and a room was prepared for Madalenna and an adjoining one for her maid. She was effusively grateful to us and kept talking of our kindness.

The excitement pleased the servants, who did all they could to make the newcomers welcome—so did the rest of us, especially Charles who was clearly taken with the Signorina’s charms.

Only Lady Sallonger felt aggrieved to have a rival invalid in the house, but it was only for a few days and even she was reconciled and during the next few days she became quite pleased to have them there. She liked to talk to Madalenna about her ailments which, she assured the young lady, were far worse than anything she could imagine; and Madalenna, who did not understand half of what she said, was too polite to show anything but absorbed interest and deep sympathy.

I think we all enjoyed her stay. It was soon clear that her ankle was not seriously damaged; she was able to hobble to the table and to and from her room; and when we were in the drawing room she would have her ankle supported on a stool or sometimes she would lie on a settee. She was very graceful, elegant and obviously well educated.

Maria, the maid, was not so fortunate. She was quietly aloof.

I supposed that was inevitable. The servants were suspicious of her. She was a foreigner who did not understand English—and that was enough to arouse their dislike. Moreover, she appeared morose; and even when kindly gestures were made they were met with something almost like hostility. She seemed to like the forest and used to go for long walks alone in it. She moved about the house silently; one would suddenly look up and see her though one had not heard her approach. Madalenna told us that it was the first time she had left Italy and she was bewildered; and that this accident should have happened had completely upset her.

Mrs. Dillon said she gave her “the creeps.”

Our recent visit to Italy made us especially interested in Madalenna. She was eager to hear what we thought of Florence and her eyes shone with pleasure when we extolled its beauty and told her how fascinating we found it all. Once I was on the point of telling her about Lorenzo but I did not do so. The memory always made me feel sad. Moreover, I thought she might fancy it was a criticism of her country as a place where law-abiding citizens could go out into the streets and be stabbed to death.

She seemed drawn to me more than to either Cassie or Julia. I thought it was because I had recently been in her country. She wanted to meet Grand’mere and I took her up to the workroom. She was most interested in the machine and the loom and the dummies and bales of materials. Grand’mere talked to her about the work she did. She fingered the material tentatively.

“What beautiful silk,” she said.

“That’s Sallon Silk,” I told her.

“Sallon Silk? What is this Sallon Silk?” she asked.

”It’s the newest kind of weaving. Can you see the beautiful sheen? We’re very proud of it. We were the first to put it on the market. It’s a great invention really. My husband says it has revolutionized the silk industry. He is very proud of it.”

“He must be,” said Madalenna. “It is interessante … to find all this … in a house.”

“Yes, it is, is it not?” I agreed. “My grandmother has been with the family for years. I have been here all my life.”

“And now you are Mrs. Sallonger.”

“Yes, Philip and I were married about six weeks ago.”

“It is very … romantico.”

“Yes, I suppose it is.”

”I hope,” she said to Grand’mere, “that you will let me come again.”

Grand’mere said she would be delighted.

Charles hovered round her. He liked to sit beside her when we were all in the drawing room; he would talk to her in his execrable Italian interspersed with English, which made her laugh; but clearly she liked his attentions.

When we were alone at night I asked Philip if he thought Charles was falling in love with Madalenna.

“Charles’s emotions are ephemeral,” he said, “but there is no doubt that he finds Madalenna very attractive.”

“It is so romantic,” I said. “She had her accident right outside the door. She might have had it five miles away and then he would never have seen her. It seems as though it was meant.”

Philip laughed at that.

“Accidents can happen anywhere. There was a weakness in the harness.”

“I like to think it was fate.”

I should like to think of Charles’s marrying for he still made me feel uneasy, and I often wondered if he still remembered that occasion when Drake Aldringham had thrown him into the lake.

Madalenna had been in the house four days when one evening the manager of the Spitalfields works came to The Silk House in some agitation. It appeared that there was a crisis at the works and the presence of both Charles and Philip was urgently needed.

Charles was annoyed. Usually he was ready to leave The Silk House after a short stay, but now that Madalenna was there he felt differently. He wanted to stay but it seemed his presence was necessary and he was finally persuaded that he had no alternative but to go.

I heard him explaining to Madalenna. “I am sure they could manage very well without me. But it will only be a day. I shall be back either late tonight or tomorrow morning.”

“I shall look forward to that with pleasure,” Madalenna told him; and Charles seemed reconciled, and with Philip and the manager, he left early the next morning.

Soon afterwards I happened to be sitting in my window when I saw Maria. She was walking towards the forest with quick, short, determined steps as though she were in a great hurry.

I watched her until she disappeared among the trees. I was rather sorry for Maria. She must find communication with the servants difficult and they were decidedly not friendly towards her. Her stay in the house was very different from that of Madalenna who had been made so much of—particularly by Charles.

It was mid morning when the carriage arrived. Cassie and I had been riding in the forest and had just come in when we saw it. I recognized it at once, as I did the coachman.

He descended from the driver’s seat and bowed to me. He then implied that he must see the Signorina at once.

“Come along in,” I said. “She is much better.”

He murmured something about God and the saints and I imagined he was offering a prayer of thanksgiving to them.

Madalenna was in the drawing room resting her leg on a stool. Lady Sallonger was there drinking her glass of sherry she took at this time. Lady Sallonger was in the middle of one of her monologues which compared her present suffering with past glories.

As I entered with the coachman, Madalenna gave a cry and got to her feet quickly. Then suddenly she winced and sat down again. She spoke in rapid Italian, to which the man replied. Then she turned to us.

“I have to leave at once. It is a message from my brother. I must meet him in London. We leave for Italy tomorrow. It is necessary. My uncle is dying and calling for me. I hope to be there in time. We are so sorry to go like this … but…”

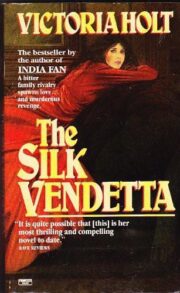

"The Silk Vendetta" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "The Silk Vendetta". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "The Silk Vendetta" друзьям в соцсетях.