“We’d borrow.”

I flinched and Grand’mere turned pale. “Never!” we said simultaneously.

“Why not?”

“Who’d lend the money?”

“Any bank. We have the security of this place … a prosperous concern.”

“And the interest on the loan?”

”We’d have to work hard to pay it.”

“I was always against borrowing,” said Grand’mere; and I nodded in agreement.

“Do you want to stay as we are forever?”

“It is a very pleasant niche we have found for ourselves,” I reminded her.

“But expansion is the very breath of successful business.”

“I believe there have been occasions when it has been their ruin.”

“Life is a matter of taking risks.”

“I want none of that,” said Grand’mere.

I backed her up in this. The thought of borrowing terrified me.

“How long would it take before a Paris place was profitable?” I asked.

“Three years … four …”

“And all that time we should have the interest on the loan to pay off.”

“We’d manage,” said the Countess.

“What if we didn’t?”

“You are prophesying defeat before we begin.”

“We have to look facts in the face. I could see us ruined and I have a child to think of.”

“When the time comes I want to launch her into society.”

“In the meantime I have to feed and clothe her, educate her too—and that is of the utmost importance to me.”

“You are really rather unadventurous,” said the Countess.

“I call it cautious,” I replied.

“So you are both against me?”

We nodded.

“Well, we shall have to shelve the matter.”

“We’ll do that,” I said.

“Meanwhile,” went on the Countess, “when I am in Paris I will scout round and see what’s to be had.”

“Whatever it is we can’t afford it.”

“You never know,” insisted the Countess.

We went on to discuss other matters.

Grand’mere and I talked about her scheme together when we were alone.

“She’s right, of course,” said Grand’mere. “The important houses do have branches in Paris. It is the centre of fashion and therefore carries a certain prestige. It would be wonderful if we could sell our clothes over there. That would be triumph indeed … and so good for business here. We could do so much better. …”

I said: “Grand’mere, are you getting caught up in this idea?”

“I realize its merits, but I am against borrowing as I always have been. I’d rather remain as we are than have to worry about loans. Remember how it was when we started and how we thought we were not coming through? “

“I shall never forget.”

“We are cosy. We are comfortable. Let’s leave it at that.”

But we both continued to think of the matter and every now and then it would crop up. It was clearly on our minds. The Countess was silent, brooding. I began to think that in time we might come round to her way of thinking.

A week or so later the Countess and Grand’mere went on one of their periodic trips to Paris.

Meetings in the Park

One of the greatest blessings of our prosperity was that I could devote more time to Katie. I had engaged a governess for her— a Miss Price—a very worthy lady, who took her duties seriously; but I often took Katie off her hands, for the child loved to be with me as much as I did with her.

We used to walk together each afternoon after her lessons. Sometimes we went to St. James’s Park where we fed the ducks; sometimes we visited the Serpentine. Katie was a very gregarious person and made friends with the other children very quickly. I liked to see her enjoying the companionship of people of her own age.

It was two days after the departure of Grand’mere and the Countess and we were sitting on a bench engaged in the sort of conversation Katie and I often had together which consisted of a number of “whys” and “whats” when a man stopped, lifted his hat and said: “So I have found you.”

It was Drake Aldringham.

“I called at your place,” he said, “and Miss Cassandra told me that you would either be in St. James’s Park or here. Unfortunately I went to the wrong one first, but at least I am now rewarded.”

I felt a great pleasure to see him.

I said: “This is Katie. Katie, this is Mr. Drake Aldringham.”

She gave him a direct look. “You’re not a duck,” she said. “You’re only a man.”

“I can see I have disappointed you,” he replied.

“Well… I’ve heard them talking about a drake.”

I was embarrassed but he looked pleased to learn that he had been the subject of our conversation.

Katie gave him one of her dazzling smiles. “Never mind,” she said.

“I’ll try not to take it to heart.”

I could see that he thought her charming and I was happy about that.

“We like it here, don’t we, Katie,” I said. “We come often.”

“Yes,” said Katie. “It’s like the country … but you can hear the horses’ hoofs and that makes it nicer.

“Grand’mere is in France,” she told Drake.

“Yes,” I added. “She and the Countess have gone to Paris.”

“Some day,” Katie said, “I shall go. With Mama, of course.”

“Of course,” he said. “Are you looking forward to that?”

She nodded. “Have you been?”

He told her he had. He talked to her about Paris and she listened avidly. A small boy came up. He was often in the park with his nanny and he and Katie played together. I could see that she wanted to go now and play with him for she looked at me expectantly.

“Yes,” I said, “but not too far. Keep where I can see you, or I shall be after you.”

She turned, smiled at Drake and was off.

” What a delightful child!” he said.

“I am so lucky to have her.”

“I can understand how you feel.”

My eyes had filled with tears and I was ashamed of myself for showing my emotions.

“She must have been a great consolation.”

I nodded. “She always has been that. I can’t imagine what I should have done without her.”

“I am so sorry it happened. It must have been devastating.”

“To have lost him in any way would have been that, but…”

“Don’t speak of it if you would rather not.”

I was silent for a few minutes. Oddly enough I did want to talk about it. I felt I could with him.

I said: “People thought he killed himself. Everyone thought that. It was the verdict of the coroner. I shall never believe it.”

“You knew him better than anyone.”

“How could he? We were so happy. We had just decided to buy a house. Why should he be so happy and then a few hours afterwards … do that? It doesn’t make sense.”

“There was nothing you knew of …”

“Absolutely nothing. It was all so mysterious. I have a theory that someone intended to kill him … and had tried before.”

He listened intently while I told him the story of Lorenzo who had gone out in Philip’s clothes.

“How very odd!” he said.

“They seemed to think I knew something which I did not divulge. It made me so unhappy. There was nothing … nothing… . Everything was perfect. …”

He put his hand over mine and pressed it.

“I’m sorry,” I said. “I got carried away.”

“I shouldn’t have brought it up.”

“You didn’t.”

“I’m afraid I did. Perhaps one day … you will grow away from it.”

“I have done that to a certain extent. Katie has helped me. And yet… she is so like him sometimes … that it reminds me. I think I shall never forget.”

”You would not, of course. But you are happy … in a way.”

“Yes, I suppose so. I have Katie, Grand’mere … good friends …”

“And the business,” he said. “You are a dedicated business woman and that means a lot to you.”

“It has. It was not until a year after Philip’s death that we started. I could not go on living in that house. It was Charles’s house and I could not forget that.”

“Of course.”

“The Countess has been invaluable to us. She is really a very lovable person. I am certainly very lucky.”

“And the prosperous business has been a great help.”

“It was not always prosperous. We were innocents, Grand’mere and I. The Countess is very worldly and I think we are becoming so under her tuition.”

“Don’t grow too worldly,” he said.

“One must be to succeed in our kind of business … or in any for that matter.”

“Success means a great deal to you.”

”It has to. It means giving Katie the sort of education I want for her … launching her into society … giving her every chance.”

“You are an ambitious Mama.”

“I am ambitious for her happiness. And we are talking too much about me. Tell me about yourself and your constituency and everything a good member of Parliament has to do.”

So he talked very amusingly and interestingly. He told me of the letters he received from some of his constituents. “A member of Parliament is expected to be a genie of the lamp,” he said. He talked too about his travels abroad, of life in the sweltering heat of the Gold Coast; how he had dreamed of coming home; and how delighted he was at last to see the white cliffs that he started to sing out loud to the amazement of his fellow travellers.

So we passed a pleasant hour watching Katie running and jumping and looking over her shoulder every now and then to smile at us.

It was a long time since I had felt so happy.

When we left he walked back to the house with us—Katie between us, each of us holding a hand.

He said how much he had enjoyed the meeting.

“Do you go to the park every day?” he asked.

“Quite often.”

“I shall look out for you.”

He bowed and smiled down at Katie. “I hope I’m forgiven for being only a man.”

“It was silly of me,” she said. “I ought to have known. Ducks don’t visit, do they?”

“No. They just quack.” He illustrated his remark with a little noise which did resemble that made by ducks. It greatly amused Katie. She quacked herself and went into the house quacking.

Cassie came out.

“Oh,” she said. “That Drake Aldringham called.”

“I know,” I told her, “we saw him in the park.”

“I told him you were there and would be somewhere near the water whichever park it was.”

“Well, he found us.”

“He’s a very nice man,” said Katie. “He quacks just like a real one … only he isn’t one, of course … only a man.”

Cassie was beaming.

“I’m glad he found you,” she said. “He was so disappointed when I told him you were out.”

And the next day we saw him again.

In fact he made a habit of meeting us in the park.

Two weeks later Grand’mere and the Countess returned home. They had been away longer than usual. I thought Grand’mere looked preoccupied. I knew her so well and she was never able to hide her feelings, so I realized that something had happened— good or bad, I was not quite sure; but it certainly had made her thoughtful.

The Countess was exuberant as she always was after her visits to Paris.

“I saw just the place that would suit us,” she said, “in the Rue Saint-Honore … quite the right spot. Small but really elegant.”

“We have made up our minds that we can’t take the risk,” I said.

“I know,” she replied sighing. “Such a pity. Chance of a lifetime really. You should see it… a lovely light workroom; and I could imagine the showroom decorated in white and gold. It would have been perfect.”

“Apart from one thing,” I said, “we haven’t the money and Grand’mere and I are determined not to be in debt.”

The Countess shook her head mournfully but said no more.

When I was alone with Grand’mere, I said to her: “Come on. You must tell me what happened.”

She looked at me in surprise.

“I know it is something,” I said. “I can see it in your face. So you had better tell me.”

She was silent for a few minutes, then she said: “The urge came over me. I had to go. I wanted to see it all again. I left the Countess in Paris and went to Villers-Mure.”

“So that was it. And it has made you thoughtful? “

”There is something about one’s birthplace …”

“Of course. It was a long journey for you.”

“I made it.”

“And how did you find it there?”

“Very much as it always was. It took me back … years. I visited your mother’s grave.”

” That was sad for you.”

“In a way. But not entirely. There was a rosebush … someone had planted it. I had expected to find the grave neglected. That cheered me a great deal.”

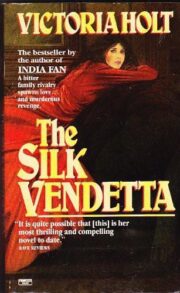

"The Silk Vendetta" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "The Silk Vendetta". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "The Silk Vendetta" друзьям в соцсетях.