I understand, Grand’mere, but I want to hear about my mother.”

“She will be happy when she looks down from heaven and seees us together. She will know what we are to each other. Sir Francis came to Villers-Mure. I remember it well. There is a family connection … you see. They say that years and years ago they were one family. Listen to their names. St. Allengere … and in English that has become Sallonger.”

“Why yes,” I cried excitedly. “So the family here is related to that one in France?”

Again that lift of the shoulders. “You will have heard from Miss Everton about something called the Edict of Nantes.”

“Oh yes,” I cried. “It was signed by Henri IV of France in the year … well, I think it was 1598.”

“Yes, yes, but what did it do? It gave freedom to the Huguenots to worship as they wished.”

“I remember that. The King was Huguenot at the time and the Parisians would not accept a Protestant King so he said that Paris was worth a Mass and he would become a Catholic.”

She smiled, well pleased. “Ah, what it is to be educated! Well, they changed it all.”

“It was called the Revocation and it was signed by Louis XIV many years later.”

“Yes, and it drove many thousands of Huguenots out of France. One branch of the St. Allengeres settled in England. They set up silk manufactories in various places. They brought with them their knowledge of how to weave these beautiful fabrics. They worked hard and prospered.”

“How very interesting! And so Sir Francis visits his relatives in France?”

“Very rarely. The family connection is not remembered much. There is the rivalry between the Sallongers of England and the St. Allengeres of France. When Sir Francis comes to France they show him a little … not much … and they try to find out what he is doing… . They are rivals. That is the way it is in business.”

“Did you see Sir Francis when you were there?”

She nodded. “There I worked as I do here. I had my loom. I knew a good many secrets … and I shall always have them. I was a good weaver. All the people who lived there were engaged in the making of silk … and so was I.”

“And my mother?”

“She too. Monsieur St. Allengere sent for me and he asked me how I would like to go to England. At first I did not know what to say. I could not believe it but when I understood I saw that it was a good thing. It was best for you and what was good for you must be for me also. So I accepted his offer which is for me to come here … to live in this house … to work the loom, when something special is required … and to make the fashion dresses which help to sell our silk.”

“You mean Sir Francis offered us a home here?”

“It was arranged between him and Monsieur St. Allengere. I was to have my loom and my sewing machine and I was to live here and do for Sir Francis what I had been doing in France.”

“And you left your home to do this … to come all this way to a country of strangers?”

“Home is where your loved ones are. I had my baby and as long as I was with you, I was content. Here, it is the good life. You are educated with the daughters of the house … and I believe you do well, eh? Miss Julia … is she not a little envious because you are cleverer than she is? And you love Miss Cassie, do you not? She is a sister to you. Sir Francis is a good man. He keeps his word and Lady Sallonger … she is demanding shall we say … but she is not unkind. We have much and we must give a little in return. I never fail to thank the good God for finding a way for me.”

I threw my arms about her neck and clung to her.

It doesn’t matter, does it?” I said. “As long as we are together.”

So that was how I learned something of my history; but I felt that there was a great deal more to know.

Grand’mere was right. Life was pleasant. I was reconciled and the slight difference with which I was treated did not worry me very much. I was not one of them. I accepted that. They had been kind to us. They had allowed us to leave the little place where everyone would know that my mother had had me without being married. I was well aware of the stigma attached to that, for there was more than one girl in the surrounding villages who had had to face what they called “trouble.” One of them had eventually married the one they called “the man” and had about six children now—but it was still remembered.

I wondered a great deal about my father. Sometimes I thought it was rather romantic not to know who one’s father was. One could imagine someone who was more exciting and handsome than real people were. One day, I told myself, I will go and find him. That started me off on a new type of daydream. I had a good many imaginary fathers after that talk with Grand’mere. Naturally I could not expect to be treated like Miss Julia or Miss Cassie, but how dull their lives were compared with mine. They had not been born to the most beautiful girl in the world; they did not possess a mysterious, anonymous father.

I realized that we were, in a way, servants of the house.

Grand’mere was of a higher grade—perhaps in the same category as Clarkson or at least Mrs. Dillon—but a servant none the less; she was highly prized because of her skills and I was there because of her. So … I accepted my lot.

It was true that Lady Sallonger was demanding. I was expected to be a maid to her. She was really beautiful—or had been in her youth and the signs remained. She would lie on the sofa in the drawing room every day, always beautifully dressed in a be-ribboned negligee and Miss Logan had to spend lots of t ime doing her hair and helping her dress. Then she would make her slow progress to the drawing room from her bedroom leaning heavily on Clarkson’s arm while Henry carried her embroidery bag and prepared to give further assistance should it be needed. She often called on me to read to her. She seemed to like to keep me busy. She was always gentle and spoke in a tired voice which seemed to have a reproach in it—against fate, I supposed, which had given her a bad time with Cassie and made an invalid of her.

It would be: “Lenore, bring me a cushion. Oh, that’s better. Sit there, will you, child? Please put the rug over my feet. They are getting chilly. Ring the bell. I want more coal on the fire. Bring me my embroidery. Oh dear, I think that is a wrong stitch. You can undo that. Perhaps you can put it right. I do hate going back over things. But do it later. Read to me now …”

She would keep me reading for what seemed like hours. She often dozed and thinking she was asleep I would stop reading, and then be reprimanded and told to go on. She liked the works of Mrs. Henry Wood. I remember The Channings and Mrs. Halliburton’s Troubles as well as East Lynne. All these I read aloud to her. She said I had a more soothing voice than Miss Logan’s.

And all the time I was doing these tasks I was thinking of how much we owed these Sallongers who had allowed us to come here and escape my mother’s shame. It was really like something out of Mrs. Henry Wood’s books, and I was naturally thrilled to be at the centre of such a drama.

Perhaps being in a humble position makes one more considerate of others. Cassie had always been my friend; Julia was too haughty, too condescending to be a real friend. Cassie was different. She looked to me for help and to one of my nature that was very endearing. I liked to have authority. I liked to look after people. I realized my feelings were not entirely altruistic. I liked the feeling of importance which came to me when I was assisting others, so I used to help Cassie with her lessons. When we went walking I made my pace fit hers while Julia and Miss Everton strode on. When we rode I kept my eye on her. She repaid me with a kind of silent adoration which gave me great satisfaction.

It was accepted in the household that I look after Cassie in the same way as I was expected to wait on Lady Sallonger.

There was one other who aroused pity in me. That was Willie. He was what Mrs. Dillon called “Minnie Wardle’s leftover.” Minnie Wardle had, by all accounts, been “a flighty piece,” “no better than she ought to be,” who had reaped her just reward and “got her comeuppance” in the form of Willie.

The child was the result of her friendship with a horse dealer who had hung round the place until Minnie was pregnant and then disappeared, Minnie Wardle thought she knew how to handle such a situation and visited the wise old woman who lived in a hut in the forest about a mile or so from The Silk House. But this time she was not clever enough, for it did not work; and when Willie was born—again quoting Mrs. Dillon—he was “tuppence short.” Her ladyship had not wanted to turn the girl out and had let her stay on, Willie with her; but before the child was a year old, the horse dealer came back and Minnie disappeared with him, leaving behind the wages of her sin to be shouldered by someone else. The child was sent to the stables to be brought up by Mrs. Carter, wife of the head groom. She had been trying to have children for some time and not being able to get one was glad to take someone else’s. But no sooner did she take in Willie than she started to breed and now had six of her own and was not very interested in Willie—particularly as he was “a screw loose.”

Poor Willie—he belonged to no one really; no one cared about him. I often thought he was not so stupid as he seemed. He could not read or write, but then there were many of them who could not do that. He had a mongrel which followed him everywhere and was known by Mrs. Dillon as “that dratted dog.” I was glad to see the boy with something which loved him and on whom he could shower affection. He seemed brighter after he acquired the dog. He liked to sit with the dog beside him looking into the lake, which was in the forest not very far from The Silk House. One came upon it unexpectedly. There was a clearing in the trees and then suddenly one saw this expanse of water. Children fished in it. One would see them with their little jars beside them and hear them shrieking with glee when they found a tadpole. Willows trailed in the water and loosestrife with its star-like blossoms grew side by side, with the flowers we called skull-caps, among the ubiquitous woundwort. I never failed to wonder at the marvels of the forest. It was full of surprises. One could ride through the trees and suddenly come upon a cluster of houses, a little hamlet or a village green. At one time the trees must have been cut down to make these habitations, but so long ago that no one remembered when.

The years had changed the forest but only a little. At the time| of the Norman Conquest it must have covered almost the whole of Essex; but now there were the occasional big houses and the old villages, the churches, the dame schools, and several little hamlets.

It was not easy to communicate with Willie. If one spoke to him he looked like a startled deer; he would stand still, as though poised for flight. He did not trust anyone.

It is strange how some people enjoy baiting the weak. Is it because they wish to call attention to their own strength? Mrs. Dillon was one of these. She it was who had stressed the fact that I was not of the same standing as my companions. It seemed to me now that instead of trying to help Willie she called attention to his deficiencies.

Naturally he was expected to help about the house. He brought water in from the well; he cleaned the yard; and these things he did happily enough; they were a habit. One day Mrs. Dillon said: “Go to the storeroom, Willie, and bring me one of my jars of plums. And tell me how many jars are left.”

She wanted Willie to come back plumless with a look of bewilderment on his face so that she could ask God or any of His angels who happened to be listening what she had done to be burdened with such an idiot.

Willie was nonplussed. He could not know how many were left; he could not be sure of picking out plums. This gave me a chance. I beckoned him and went with him to the storeroom. I picked out the plums and held up six fingers. He stared at me and again I held up my fingers; at last a smile broke out on his face.

He returned to the kitchen. I think Mrs. Dillon was disappointed that he had brought what she had asked for. “Well,” she demanded, “how many’s left?” I hovered in the doorway and behind Mrs. Dillon’s back I held up six fingers. Willie did the same.

“Six,” cried Mrs. Dillon. “As few as that. My goodness, what have I done to be given such an idiot.”

” It’s all right, Mrs. Dillon,” I said. ”I went and had a look.

There are six left.”

“Oh, it’s you, Lenore. Poking your nose in as usual.”

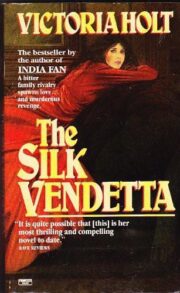

"The Silk Vendetta" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "The Silk Vendetta". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "The Silk Vendetta" друзьям в соцсетях.