The rest of that visit was something of an anticlimax. Everyone seemed embarrassed except Katie. She wanted her riding lesson which Drake gave her, and she seemed completely happy.

Isabel made Patty stay in bed for the next day.

“The poor girl is really shaken,” she said. “She’s the hysterical type.”

Everything had turned out so differently from what I had expected. I could see that Grand’mere was disappointed and Cassie seemed merely bewildered. It was rather a relief to leave—but Katie felt very sad.

“It has been lovely,” she said, flinging her arms round Drake. “Take care of Bluebell till I come back.”

Drake assured her that he would make sure that the pony was well cared for.

We left Julia there. She was one at least who had enjoyed Christmas.

It was about two days later when Grand’mere said that she wished to talk to me alone for she had something very important to say to me.

”Lenore,” she began, ”you know that I went to Villers-Mure not long ago.”

“Yes, Grand’mere.”

“When I was there … I met someone.”

“Who?”

“I met… your father.”

“Grand’mere!”

“It’s true.”

“I thought you did not know who my father was.”

She was silent. “I have told you something of our family history. It is not always easy to explain to a child. To talk of it was most upsetting and I am afraid I was something of a coward.”

“Tell me now.”

“You know that your mother, my daughter Marie Louise, was a girl of exceptional beauty. It was natural that she should attract men. We were humble. I was left a young widow and had to work for my living and like most people in Villers-Mure I worked at the St. Allengere establishment, and when Marie Louise was old enough she was given a place there. You know what happened. She fell in love. You were born. She died … perhaps of fear and grief. Women do die in childbirth even when the future is bright for them. I do not know… . All I know is that she died and I was heartbroken …for she was my life… . Then I realized that she had left me you … and that changed everything.”

“Yes, Grand’mere, you have told me this.”

“You knew that the great Alphonse St. Allengere arranged for me to come to England to work for the Sallongers. The reason he did that was because he did not want me to remain where I was.”

“Why?” I asked. Grand’mere was finding it difficult to tell me this; she was not her usual loquacious self.

She frowned and said: “Because your father was his youngest son.”

“So … you did know who my father was!”

“Marie Louise told me … just before you were born.”

“And he would not marry her?”

“He was only a boy. Seventeen years old and I can tell you Alphonse St. Allengere is a very formidable man. The whole of Villers-Mure went in fear and trembling of him. He held our lives in the palm of his hand. Everyone dreaded his frowns, his sons no less than any others. There was no question of a St. Allengere marrying one of the girls who worked in the factory. Your father did his best. He truly loved Marie Louise, but his father was adamant. He was sent away to an uncle who owned a vineyard in Burgundy. When I went to Villers-Mure I made enquiries. By great good fortune he was on a visit to his family so I was able to talk to him. I told him about you … how you were now a widow with a young child. He was very touched.” “I knew there was something. I could see it in your face when you returned.”

“He is in London now.”

I stared at her.

She nodded happily. “Yes, he has said he must see you. Naturally he wanted to know his own daughter. He is coming here.”

She looked at me intently as though to assess the effect of this bombshell. I have to admit that I was astounded. To be brought face to face with a father one has never known could be a shattering experience. I was not sure whether I looked forward to it or dreaded it.

Grand’mere went on: “It is not natural for those who are so close to be strangers to each other.”

“But after all these years, Grand’mere …”

“Ma cherie, he longs to meet you. You could make him very happy. He has come all this way to see you.”

“When is he coming?”

“This evening. I have asked him to dine with us.”

“But… this is so unexpected. …”

“I thought it wise not to tell you until it was all arranged.”

“Why?”

“I did not know how you would feel. Perhaps there would be some resentment. All those years he has not seen you … The years of struggle for us. He is a very rich man. He owns vineyards in various parts of France. The St. Allengeres are always successful whatever they take up. His father is proud of him now. It is a different matter from when he was young.”

”I do not greatly care for this father of his …my grandfather, I suppose.”

“He had great power. And sometimes that is not good for people. He is old now but he is still the same Alphonse St. Allengere. He still rules Villers-Mure and is undoubtedly the greatest producer of silk in the world.”

“And tonight…”

She nodded.

I was so overcome that I found it difficult to analyse my feelings. Should I tell Katie? What should I say to her? “This is your grandfather.” She would ask interminable questions. Where had he been all this time?

Fortunately she would be in bed before he came and I should have a chance of meeting him and perhaps breaking the news gradually of how a grandfather had appeared out of the blue.

I dressed carefully in a scarlet gown and waited in trepidation for his coming. Grand’mere was rather agitated, too. I was glad that the Countess and Cassie were present. They helped to subdue the emotion which Grand’mere and I were feeling.

At the appointed hour the doorbell rang. Rosie, our maid, announced him.

“Mr. Sallonger,” she said, finding it impossible to pronounce his name and giving the anglicized version.

And there he was.

I looked at him in amazement. He was the man I had seen in the park, the one who had retrieved Katie’s ball and had appeared to be watching me.

What an exciting evening that was! So much was said that it is difficult for me to remember now and in what order. I remember his taking both my hands and looking into my eyes. He said: “We have met before … in the park.”

I nodded in agreement.

“I was on the point of making myself known many times,” he went on, “but I hesitated. Now … we are together at last.”

How amazing it was, I thought, that when I had seen him in the park I had believed him to be a stranger; and he was in fact my father!

During the dinner, at which Cassie and the Countess were present, he talked about his vineyards. He spoke in English and now and then had to grope for the words he needed. He wanted to hear of our salon and the Countess was most voluble on the subject.

She talked amusingly of our clients and the manner in which they followed each other like sheep. One had a Lenore gown and they all must. It was inevitable that she should come to the matter which was uppermost in her mind.

“By hook or by crook I shall get us to Paris,” she said. “That is the centre of fashion and worthwhile houses must in time have connections there. It is an essential in the long run.”

“I can see that,” he said. “And at the moment you have not this … connection?”

“No, but we will.”

“When do you propose to set up there?”

“When we have the good fortune … and I mean fortune … so to do,” said the Countess. ”I’m all for it but my partners are cautious. They want to wait until we can pay for it. The good Lord knows when that will be.”

He nodded gravely and Grand’mere abruptly changed the subject.

After dinner, the Countess and Cassie left him alone with me; and then we spoke in French of which language I had been made fairly fluent by Grand’mere; and of course she was in her natural element.

“I have thought of you often,” he said. “I have wanted so much to find you and when your grandmother came to Villers-Mure and I happened to be visiting my family home it seemed like Providence. She told me a great deal about you. How you had this wonderful business. The St. Allengeres always prospered in business.”

“Our prosperity is largely due to the Countess, is it not, Grand’mere? She is a superb saleswoman, and she showed us what innocents we were. We should have foundered without her.”

“I want to know a great deal about your business. But first let us talk about ourselves. You must understand that I truly loved your mother. It was the shame of my life that I let myself be sent away. I should have stood by her. I should have defied my father. But I was young … I was weak and foolish. I was not strong enough. I should have married her. Instead I let them send me away.”

Grand’mere nodded.

He looked at her and said: “How you must have reviled me when I did.”

“Yes,” said Grand’mere frankly, “I did. Marie Louise did not blame you. She defended you to me. She said you did what you had to do. Your father was determined and he is a very powerful and ruthless man.”

“And still is,” he added grimly. “It was good for me to escape from his domination. I found my life among the vines rather than the mulberries. But it is all so long ago.”

“And nothing can bring Marie Louise back.”

“Perhaps she would have died in any case,” I said.

They were silent.

Then he told us how he had gone away to stay with his uncle who owned a vineyard and how he became interested in wine. “I threw myself into the work,” he said. “It was a solace. My uncle said that I should be a good vintner. So I stayed with him. Then I had my own vineyards. I worked hard. I married my wife who brought me property, and now we have our family.”

“And you are happy?” I said.

“I do not complain. I have a son and a daughter.”

“I saw Marie Louise’s grave had not been neglected,” said Grand’mere.

“I always go there when I visit the family. And I have paid one of the peasants to look after it. If it is possible that she could be aware she will know that I have not forgotten.”

He and Grand’mere talked of my mother for a while—how pleased and proud she would have been of me and Katie—whom he had found enchanting. It had delighted him to realize that she was his granddaughter.

“And you have suffered,” he said to me. “Madame Clere-mont has told me of your husband’s death and how you have devoted yourself to that dear child.”

“She is a great joy to me,” I told him.

We fell into silence again and after a while he said: “I was interested in what the Countess was saying about your salon, and how she thought you should open in Paris. She is right, you know.”

“Oh yes, we know she has a point, but my grandmother and I are against it… for the time being at any rate. We have not been so very long in business here and once … in the beginning … we came near to disaster. That has made us cautious.”

“But,” he said, “it is a move you must take.”

Grand’mere was watching him intently and I had a notion that she knew what he was going to say.

It came. “Perhaps I could be of assistance.”

I looked at him in astonishment.

He went on: “It is something I should dearly love to do. I am not a poor man. I have my vineyards. We have good years when all goes well; the weather is kind to us, and the leaf hoppers and the rot worms decide to leave us alone… . Then we make good profits. I have not done too badly. I would take it as a privilege if you would allow me to help with this Paris addition.”

“Oh,” I said quickly, “that is good of you but, of course, we don’t want to borrow money. …”

“How right you are. What does your Shakespeare say: ‘Neither a borrower nor a lender be… .’ But I was not thinking of a loan. You are my daughter. Should there not be these things between a father and his daughter? Let me finance this Paris branch … as a kind of dowry to my daughter.”

I drew back in horror. I looked suspiciously at Grand’mere. She was sitting with her eyes downcast and her hands in her lap. She dared not let me see her face because she knew it would be shining with triumph.

“I could not accept that,” I said sharply.

”It would give me great pleasure.”

“Please think no more of it.”

He looked at me sadly. “I see you do not accept me as a father.”

I stammered: “I have met you for the first time tonight. We cannot count those meetings in the park. And you offer this! Do you realize what such an undertaking would cost?”

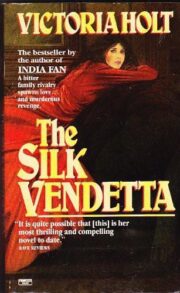

"The Silk Vendetta" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "The Silk Vendetta". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "The Silk Vendetta" друзьям в соцсетях.