Then I went to my room. I undressed, but before getting into bed I opened the windows and went out onto the balcony. It looked dark and mysterious—the stars brilliant in the clear air; and seeming closer than it did by day. There it was—the Chateau Carsonne, arrogant, mighty, menacing in a way. I found it difficult to withdraw my gaze from it.

Finally I went to bed but I found sleep elusive. I kept thinking of all the events of the day and when I did sleep it was to be haunted by dreams in which my wicked grandfather loomed large and the Chateau Carsonne was a prison in which he had decided to shut me up because I had dared come into his territory against his wishes.

When I awoke the dream lingered. It made me feel very uneasy and the first thing I did on rising was to go out to the balcony and look at the Chateau Carsonne.

A few days passed with rapid speed. Ursule and Louis departed, Ursule insisting that we visit them soon. I assured her mat there was little I should like more. We were good friends already.

“We are always in a little turmoil here at the time of the vendange,” said my father. “An excitement grips the household. It is the culmination of a year’s hard work… all the trials we have undergone … all the anxieties as to whether or not there would be a good harvest or no harvest at all … that is over, and this is the achievement.”

“It’s understandable.”

“If you knew what we have suffered. It has been a little damp this year and we have had to keep a watch for mildew. Apart from that it has been a fairly good season. And now it is over and everything is being gathered in. Hence the jubilation and the anticipation of the great climax.”

There were horses for both Katie and me and we loved to ride round exploring. Katie was quite a good rider by now, but at this time her chief interest was in the wine harvest.

She liked to go off with my father and he liked to have her with him; this gave me an opportunity to ride out alone.

I knew that Katie was safe and happy with my father and so I could give myself up to the complete enjoyment of exploring the countryside.

It was some four days after our arrival when the whole countryside seemed to be taking its afternoon siesta. I donned my riding habit and went down to the stables.

My father had suggested I use a certain chestnut mare. She was smallish and not over-frisky, but at the same time she had spirit. We suited each other; and that afternoon I rode out on her.

I found myself going in that direction where lay Villers-Mure. There was one point where I could ride up to the top of a ridge of hills and look down on the valley. It was becoming a favourite spot of mine and I knew that one day I should be tempted to ride down the slopes and into that village.

On this afternoon I went to this spot. From where I was I could see the mulberry bushes and the manufactory with its glass windows in the distance. It did not look like a factory. A small stream ran past it and there was a bridge over it on which creepers grew; it was very picturesque. I could see the towers of the big house and I wondered what my grandfather was doing at that moment and whether he was aware that his granddaughter was close by.

One day, I thought, I will ride down there. I will find the house where Grand’mere lived with her daughter; and I wondered if my mother had ever come up here and stood on this very spot, where she and my father had met, where I had been conceived. This was the place of my birth and I was forbidden to go to it.

I turned away. The sun was hot this afternoon. Away to my right the thicket looked cool and inviting and I could smell the redolence of the pines. I turned the chestnut towards the thicket. The trees grew more closely together as I progressed. It was beautiful… the smell of damp earth … the sudden coolness and the scent of the trees. I rode on deeper into the wood. I wondered how far it extended. It had seemed quite a small wood when I had first seen it and I was sure that if I went on I should emerge soon.

I heard the bark of a dog. Someone was in the woods. Or perhaps it was just a dog. The barking was coming nearer. It sounded fierce, angry. Then suddenly two Alsatian dogs were visible through the trees. When they saw me they gave what sounded like a yelp of triumph and they were bounding towards me. They stopped abruptly, looking straight at me, and their barking was truly menacing. I felt the chestnut quiver. She drew her head back. She was very uneasy.

“Go away,” I cried to the dogs forcing a note of authority into my voice which seemed only to infuriate them the more, for their barking intensified and they looked as though they were ready to spring at me.

To my relief a man had come riding through the trees. He pulled up sharply and stared at me.

Then he said: “Fidele. Napoleon. Come here.”

The dogs stopped their barking immediately and went to stand beside his horse.

In those few seconds I noticed a good deal about him. He was riding a magnificent black horse and he sat it as though he were part of it. He reminded me of a centaur. His eyes were very dark and heavily lidded and his eyebrows were firmly marked. His hair under his riding hat was almost black. His skin was fair which was one of the reasons why he was so striking. It made such a contrast to dark hair and eyes. His nose was what I call aggressive—long, patrician, reminding me of the pictures I had seen of Francois Premier. His mouth was the most expressive part of his face. I imagined it could be cruel and at the same time humorous. He was one of the most striking looking men I had ever seen and that was the reason why I could take in so much in such a short time.

I knew at once that he was a man of power who set himself above others and he was as accustomed to obedience from those about him as he was from his dogs. He was now studying me with those strongly marked eyebrows slightly raised. His gaze was penetrating and I felt uncomfortable beneath it. I was vaguely irritated by the intensity of his inspection and I could not refrain from showing my displeasure.

I said: “I suppose these are your dogs.”

“These are my dogs and these are my woods and you are trespassing.”

“I am sorry.”

“We prosecute trespassers.”

”I had no idea that I was doing so.”

“There are notices.”

“I am afraid I did not see them. I am a stranger here.”

“That does not excuse you, Mademoiselle.”

“Madame,” I said.

He bowed ironically. “A thousand apologies, Madame. May I know your name?”

”Madame Sallonger.”

“St. Allengere. Then you are connected with the silk merchants.”

“I did not say St. Allengere but Sallonger. That was my husband’s name.”

“And your husband … he is here with you now?”

”My husband is dead.”

“I am sorry.”

“Thank you. I will now leave your woods and apologise for the trouble I have caused if you and your dogs will allow me to pass.”

“I will escort you.”

“There is no need. I am sure I can find my way.”

“It is easy to lose oneself in the woods.”

“They did not seem to me to be so very extensive.”

“Nevertheless … if you will allow me.”

“Of course. You will want to make sure that I leave your property at once. I can only say I am sorry for the intrusion. It shall not happen again.”

He approached me. I patted the chestnut and murmured words of reassurance. She was still disturbed by the dogs.

“She seems restive,” he said.

“She does not like your Fidele and Napoleon.”

“They are a very dutiful pair.”

“They look vicious.”

“They could be in the course of their duty.”

“Which is to keep trespassers from your land.”

“That among other things. Come this way.”

He rode beside me and we went through the woods, the dogs docile now, accepting me and the chestnut as approved by then-master.

He said: “Tell me, Madame Sallonger, are you visiting this place?”

“I am here with my father, Henri St. Allengere.”

”Then you are one of them.”

“I suppose so.”

“I see. Then I believe I know exactly who you are. You are that one whose grandmother took her to England which accounts for your accent and that somewhat foreign aspect.”

“I’m sorry for the accent.”

“Don’t be. It is charming. You speak our language fluently, but there is just that little betrayal which gives you away. I like it. As for your foreign ways … I like those too. Vive la difference.”

I smiled.

“Now,” he went on, “you are asking yourself, who is this arrogant man who has dared accost me and driven me from his woods? Is that so?”

“Well, who is he?”

“Not a very pleasant character, as you will have gathered.”

He was looking at me expectantly but I did not answer. That amused him. He laughed. I turned to look at him. He was like a different person now. His eyes were brilliant…full of laughter. His mouth had changed too: it had softened.

“And you would be perfectly right,” he said. “My name is Gaston de la Tour.”

”And you live hereabouts?”

“Yes, close by.”

“And you own the woods of which you are very proud and eager to keep to yourself.”

“Correct,” he agreed. “And I resent others using them.”

“They are so beautiful,” I said. “It is a shame to keep them to yourself.”

“It is because they are beautiful that I want to. You see, I am entirely mean-spirited.”

“What harm do people do in your woods?”

“Little, I suppose. But let me think. They might damage the trees … start fires. But the real reason is that I like what is mine to be mine alone. Do you think that is reprehensible?”

“I think it is a common human failing.”

”You are a student of nature?”

“Aren’t you?”

“I am self-absorbed … a quite impossible creature really.”

“You have one virtue.”

“Pray tell me what good you have discovered in me?”

“You know that you are … your own words … quite impossible. To know oneself is a great virtue and so few of us have it.”

“What a charming trespasser you are! I am so glad you took it into your head to come into my woods. Please tell me, Madame Sallonger, how long will you stay among us?”

“We have come for the vendange.”

“We?”

“My daughter and I.”

“So you have a daughter.”

“Yes. She is eleven years old.”

“We have something in common. I have a son. He is twelve years old. So we are both … parents. There is something else. You are a widow. I am a widower. Is that not interesting?”

”I don’t know. Is it? There must be a great many widows and widowers in the world. I suppose they meet fairly frequently.”

“You are so prosaic … calm … logical. Is that the English in you?”

“Actually I am French by birth, English by education and upbringing.”

“The latter probably forms one’s nature more than anything. I’ll tell you something. I know exactly who you are. I was eight years old at the time. So you now know my age. In a place like this people know the business of others. It is a place where it is impossible to have secrets. There was a big furore. Henri St. Allengere and the young girl… one of the beauties of the place … the wicked old man who blighted their lives. Blighting lives is a habit of old Alphonse St. Allengere. He is one of the ogres of the neighbourhood … quite the most monstrous.”

“You are right in thinking he is my grandfather.”

“Condolences on that point.”

“I see you do not like him.”

“Like him? Does one like a rattlesnake? He is well known throughout this neighbourhood. If you go to the church you will see the stained glass windows restored by the benevolence of Alphonse St. Allengere. The lectern is a gift from him. The roof is now in excellent condition. Through him war was declared on the death watch beetle; the church owes its survival to him. He is God’s good friend and man’s worst enemy.”

“Is that possible?”

“That is something, my dear Madame Sallonger, which you with your knowledge of human nature, will be able to decide more easily than I.”

I said: “It is a long way through the woods.”

”I am glad of it. It gives me a chance to enjoy this interesting conversation.”

I was suspicious suddenly. It had not taken me long to reach that spot where the dogs had found me. He saw my look, interpreted it and smiled at me ingratiatingly.

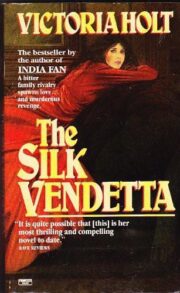

"The Silk Vendetta" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "The Silk Vendetta". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "The Silk Vendetta" друзьям в соцсетях.