“I understand you very well. I will tell you the truth. I have enjoyed our meetings, but I do not attach any significance to them.”

He sighed. “I see how difficult it is to convince you of my feelings.”

“Not difficult at all. I understand perfectly. I shall really have to go back now. I have preparations to make.”

“Suppose I were to ask you and your father to a musical entertainment at the chateau. I could get some well-known musicians to play for us. Do you like music?”

“I do. But we could not accept your invitation. We have to leave at the end of the week.”

“I am interested to discover what happened to your husband. I think the matter should not be dismissed lightly. I think we should try to solve the mystery. Once you know the truth you will cease to think so constantly of him. You will grow away from the tragedy. You will see that life is for living not brooding over the dead and dreaming of what might have been.”

“This has very little to do with my relationship with you.”

“Oh, it has, I am sure.”

“I am taking this turning back. It is a short cut to the house.”

As it came into sight with its surrounding vineyards I pulled up.

“In case I don’t see you before I go, I will say goodbye.”

“This sounds like dismissal.”

“That’s absurd. It is just… goodbye.”

He took my hand and kissed it.

“This is not the end, you know,” he said.

And I felt a lightness of heart for I should have hated it to be the end.

I withdrew my hand.

”Au revoir,” he said.

I turned and rode away.

When I am busy in Paris I shall forget all about this, I told myself. What would involvement with him mean? A brief love affair. Not marriage. The idea of marriage with him was a disturbing thought. It would be stimulating and exciting. But he had never mentioned the possibility of marriage. That was another reason why I should get away.

Of course he had no intention of marrying. The only time he had talked of it was in connection with Evette whom he had married to please his family. He had produced the heir and he would never want to enter the bonds of matrimony again. Although why a man such as he was should have such an aversion to it I could not understand, for he would never keep his vows if he did not want to. He would be a typical French husband … courteous, paying attention to his wife and doing what he called his duty and then being off to take pleasure with his mistresses.

That was manage a la mode according to the worldly ways of the French nobility.

It was not for me.

Before I left I wanted to see my mother’s grave. I knew that she was buried in the graveyard of the little church of Villers-Mure. My father had not wished me to go near his old home. I think he feared what my grandfather’s reaction might be if he heard that I was there. I did not want to involve him but I was determined to go.

The day before we were due to leave, I set out.

I came to the hill from which I could look down on the St. Allengere property. I could see the village close to the manufactory, and the little river winding its way past the stone buildings and under the little bridge. It was a charming sight.

I could see the spire of the church and I made my way down the hill towards it.

There was no one about. I expected they were all at work. I came to the church and tethered my horse outside. I entered and my footsteps, echoing on the stone flags, broke the silence. It was awe-inspiring to think that this was the church where my mother and Grand’mere must have sat so often together. The windows were magnificent. There was the Jesse window presented by a Jean Pascal St. Allengere in the sixteenth century; and the parable of the loaves and fishes by Jean Christophe St. Allengere a hundred years later. There was St. John the Baptist. “Presented by Alphonse St. Allengere.” I stood staring at his name. My grandfather! I remembered what the Comte had said about him and could not help smiling.

The name St. Allengere appeared in several places. They had been benefactors of the church throughout the ages. I was trespassing. I should not be here. My father did not wish it. I wondered what my grandfather would say if he knew I had ventured into his territory.

I felt suddenly warm so I took off the scarf I was wearing. I studied the ornate altar, the lectern… another gift to the church from my pious grandfather. There was evidence everywhere of his generosity.

This was his church. The castle would have its own chapel, I supposed, so the Comte would never come here. He would be quite different from my grandfather; if his flippant conversation was an indication of his beliefs he was certainly not devout.

I came out into the fresh air and made my way to the graveyard.

Ornate statuary had been placed over many of the graves. There were angels in plenty and figures of the saints. Some of them were so large and lifelike that one almost expected them to speak.

I did not think my mother would be among those with the elaborate sculptures, but there among the most magnificent were the burial grounds of my ancestors. The name St. Allengere was on many of the headstones. I went to the most ornate of them all. Marthe St. Allengere; wife of Alphonse 1822-1850. So that was my grandmother. She had been young to die. I daresay childbearing and life with Alphonse had taken their toll. I walked on and found the grave of Heloise. There was no elaborate statue there. It was an inconspicuous little grave, but all the plants on it had been well tended. There was a white urn from which grew pale pink roses. Poor Heloise! I wondered about her. How she must have suffered. I thought of the Comte. Of course he may not have been the man involved with the tragic girl. I was being unfair to him to be so sure that he was he. I had no reason for doing so except that he was the man he was. Heloise was a beautiful girl, and I knew that he would take great delight in seducing the daughter of the enemy house.

I passed on. It was some time before I found my mother’s grave. It was in a corner among those of the less flamboyantly decorated. It just said her name, Marie Louise Cleremont. Died aged 17. I felt an intense emotion sweep over me and I saw the rose bush which had been planted there through a haze of tears.

Her story was not unsimilar to that of Heloise. But she had died naturally. I was glad she had not given up. I had robbed her of her life. Had she lived, we should all have been together, she, Grand’mere and I. Poor Heloise had been unable to face life. Hers was a different story although it had begun as my mother’s had with a lover who had failed her. A lesson to all frail women.

I turned away and started to make my way back to the church door where I had left Marron. In doing so I had to pass the St. Allengere section and I was startled to see a man standing by Heloise’s grave.

He said,’ ‘Good day,” and as I returned his greetings I could not resist pausing.

“A fine day,” he said. Then: “Have you lost your way?”

“No. I have just been having a look at the church. I left my horse tethered at the door.”

”It’s a fine old church, is it not?”

I agreed that it was.

”You are a stranger here.” He looked at me piercingly. Then he said: “I believe I know who you are. Are you staying by any chance at the vineyards?”

“Yes,” I told him.

“Then you are Henri’s daughter.”

I nodded, and he looked rather emotional.

“I heard you were there,” he said.

“You must be … my uncle.”

He nodded. “You are very like your mother… so like her, in fact, that for the moment I could believe that you were she.”

“My father said there was a resemblance.”

He looked down at the grave.

“Have you enjoyed your visit here?”

“Yes, very much.”

”It is a pity that it has to be as it is. And Madame Cleremont, she is well?”

”Yes, she is in London.”

“I have heard of the salon. I believe it prospers.”

“Yes, now we have a branch in Paris. I am going back there tomorrow.”

“I believe,” he went on, “that you are Madame Sallonger.”

“That is so.”

“I know the story, of course. You were brought up by the family and in due course married one of the sons of the house. Philip, I believe.”

“You are very knowledgeable about me. And you are right. I married Philip.”

“And you are now a widow.”

“Yes, I have been a widow for twelve years.”

The scarf which I was carrying had caught in a bramble. It was dragged from my hands. He retrieved it. It was silk, pale lavender, and similar to those we sold in the salon.

He felt its texture and looked at it intently.

“It is beautiful silk,” he said. He kept it in his hands. “Forgive me. I am very interested in silk naturally. It is our life here.”

“Yes, of course.”

He still kept the scarf. “This is the best of all silks. I believe it is called Sallon Silk.”

“That is true.”

“The texture is wonderful. There has never been a silk on the market to match it. I believe your husband discovered the process of producing it and making it the property of the English firm.”

“It is true that it was discovered by a Sallonger, but it was not Philip, my husband. It was his brother, Charles.”

My uncle stared at me incredulously.

“I was always of the opinion that it was your husband. Are you sure you were not mistaken?”

“Certainly I am not. I remember it well. We were amazed that Charles should have come up with the formula because he had always given the impression that he was by no means dedicated to the business. My husband was … absolutely. If anyone should have discovered Sallon Silk it should have been him. But it was most definitely Charles. I remember it so well. It was a brilliant discovery and we owe it to Charles.”

“Charles,” he repeated. “He is the head of the business now?”

“Yes. It was left to the two of them, and when my husband … died … Charles became the sole owner.”

He was silent. I noticed how pale he was and his hands shook as he handed me back the scarf.

He lifted his eyes to my face and said: “This is my daughter’s grave.”

I bowed my head in sympathy.

He went on: “It was a great grief to us all. She was a beautiful gentle girl… and she died.”

I wanted to comfort him because he seemed so stricken.

He smiled suddenly: “It has been interesting talking to you. I wish … that I could invite you to my home.”

I said: “I quite understand. And I have enjoyed meeting you.”

“And tomorrow you are leaving?”

“Yes. I am returning to Paris tomorrow.”

“Goodbye,” he said. “It has been most… revealing.”

He walked slowly away and I made my way back to Marron.

Our last evening was spent with Ursule and Louis in their little house on the Carsonne estate. It was a pleasant evening. Ursule said how she always looked forward to Henri’s visits and she hoped that now I had come once I would come again.

I told them how interesting it had all been. I mentioned to them that I had been to the graveyard to see my mother’s grave and had there met Rene. At first my father was taken aback but then he was reconciled.

“Poor Rene,” he said. “Sometimes I think he wishes he had had the courage to break away.”

“He is our father’s puppet,” replied Ursule rather fiercely. “He has done all that was expected of him and his reward will be the St. Allengere property in due course.”

“Unless,” said Louis, “he does something to earn the old man’s disapproval before he dies.”

“I am glad I chose freedom,” said Ursule.

Later they talked about the Comte.

“He’s a good employer,” said Louis. “He gives me a free hand and as long as I keep the Carsonne collection in order I can paint when I will. Occasionally he arranges for me to have an exhibition. I don’t know how we should have come through without his father and now him.”

“He does it all to spite our father,” said mine.

”The Comte has a fine appreciation of art,” said Louis. ‘ ‘He respects an artist and I think he is not unimpressed by my work. I owe him a great deal.”

“We both do,” said Ursule. “So Henri, do not speak harshly of him in our household.”

“I admit,” said my father, “that he has been of use to you. But his reputation in the neighbourhood …”

“That’s a family tradition,” insisted Ursule. “The Comtes of Carsonne have always been a lusty lot. At least he doesn’t assume the mask of piety like our own Papa … and think of the misery he has caused.”

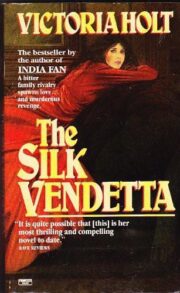

"The Silk Vendetta" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "The Silk Vendetta". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "The Silk Vendetta" друзьям в соцсетях.