“I’m sorry to have wasted your time, sir. I’ll leave you to your more important affairs and wish you good day.” She took up her loose-leaf notebooks, and as she turned away, she had the unmistakable impression that he brushed off the corner of the desk where they had lain, polluting it.

She trudged back through the wet snow toward the offices of the Commissariat of Armaments, cold moisture seeping into her boots. Grushenka, you bitch. If not for you, I’d be home in Washington doing my job.

The unexpected sight of the changing guard at the Kremlin Palace brought her to a halt. She watched as the sentries marched toward one another, saluted, executed an elaborate double about-face, and separated. Only when the relieved sentry began the return march did she recognize him. The handsome, amiable Kiril.

He marched stiffly and in step with his colleague toward the Arsenal, his ceremonial rifle on his shoulder. She couldn’t interfere with the ritual so she discreetly followed him all the way to the entrance of his barracks. Only when he relaxed his guard and signaled good-bye to his mate did she run to intercept him.

“Kiril, stop,” she called out, and caught up with him on the steps. “Do you remember me?”

He smiled warmly. “Yes, of course I do, Miss Kramer. The American lady who wanted to go to church. It’s nice to see you again. What brings you to the Kremlin? You are without escort this time.”

“Yes. This time I’m not a guest of Marshal Stalin, only an annoying secretary of Mr. Hopkins trying to get information. But I was wondering, is Alexia Vassilievna still with the Kremlin Guard? I’d love to see her again.”

“No. She was transferred shortly after you left in January. To the sniper’s school at Podolsk.” He counted on his fingers, calculating the time elapsed. “I’m sure she’s graduated by now.”

“Ah, I see. Do you know where they go after graduation?”

“I can’t say for certain, but the last report in The Red Star was that female snipers were very successful on the Novgorod front. She’s probably based somewhere around there.”

“Have you heard from her?”

“No, but she wouldn’t write to me. Her grandmother, maybe.”

“Well, thank you, Kiril. I won’t keep you any longer. Take care of yourself.” She exchanged a warm handshake and turned, twice defeated, toward the Commissariat of Armaments.

Dmitriy Ustinov was more welcoming than Molotov had been and even made room for her books on his desk. “I see you’ve been hard at work,” he said, running his finger down the summary inventory page. “Have you pinpointed where the discrepancies begin in the delivery chain?”

“Not yet, but I’m much better prepared now. I’ve spent the last two and a half months making parallel lists of the items that seem to have disappeared, and at this point, I need to see the receipts from each distribution spot.”

“Receipts. Yes, of course,” he muttered. At the sound of a door opening, he glanced up. “Oh, there you are. Miss Kramer, you remember Colonel Nazarov, my deputy?”

The stocky man she remembered from her last visit shook her hand warmly. “So glad to see you again,” he said. “I haven’t forgotten our very jolly dinner last January with the boss.”

Mia instantly liked this man. “That’s an evening I will never forget. Marshal Stalin was in top form all evening, wasn’t he?”

“He surely was.” Nazarov hooked his thumbs in his belt like some jovial grandfather.

“Colonel Nazarov has just come from a tour of various factories,” Ustinov said. “Have you found everything in order, Nazarov?”

“I was just about to make a report on that subject exactly. Yes, within normal parameters, the distribution matches the inventory given to me. If deficiencies exist, we must look elsewhere.”

“What sort of factories do you refer to, Colonel Nazarov?” Mia asked.

“The Tankograd tank factory in Chelyabinsk, another in Kovrov assembling field telephones, and the Tula rifle factory.”

“Has the food arrived as well?” Mia asked. “I mean the tons of canned meat sent along with the shipments of arms. We know that an army marches on its stomach. And so do the workers who produce their weapons.”

“Oh, yes. Plenty of Spam on hand in all three factories. Our workers are very grateful for that.”

“And front-line supplies?”

“I’m checking on them the day after tomorrow when the next supply plane goes to Novgorod.”

The door to the office opened, and all three of them turned as an adjutant stepped into the opening. “Excuse me, Colonel Nazarov. A telephone call. From General Molotov.”

“Ah, yes. Will you excuse me? A good man never finds rest, eh?” He saluted Ustinov, offered a quick handshake to Mia, and marched from the room.

Mia had a sudden idea. “General Ustinov. I’ll take your lists with me and study them this evening, but would I be able perhaps to visit the rifle factory Colonel Nazarov mentioned?”

Ustinov hesitated. “Arms factories are usually off-limits to foreigners.”

“Yes, sir. But I do represent the agency that supplies so many of your weapons and so don’t fall into the category of ‘ordinary foreigner.’ I think you could make a case that Mr. Hopkins and I are part of the Soviet munitions production.”

He scratched in front of his ear. “I see your point, Miss Kramer. All right. I’ll write a pass authorizing your visit. Fortunately, the train from Moscow passes near the factory.”

“Thank you, Commissar Ustinov.” She held out little hope that the visit would produce anything, but it would at least show Hopkins that she’d gone all the way to the end of the distribution line.

And it would certainly be interesting to see how rifles were made.

Upon her return to the embassy, she discovered Ambassador Harriman had arrived, and she joined him in the dining room.

“How did it go?” he asked, pouring her a glass of wine. Another benefit of living at the embassy, however cold and windowless it was.

“Good and bad. Molotov is still being uncooperative. He complains but does nothing to assist us. He’s such an—” She stopped as he raised a finger to his lips, and she remembered all the eavesdropping bugs.

“Soo… let me say that my main problem all day was wet feet.” She drew a pencil from her pocket and wrote on a napkin.

Losses seem to occur between depots and factory. I think it’s either Molotov or Ustinov.

“Wet feet all day is dangerous. So what do you plan to do?” he replied to her small talk.

“I suppose I’ll have to look around for some rubber boots, won’t I?” She scribbled another line on the napkin.

Going to an arms plant in Tula tomorrow, with Ustinov’s permission. Maybe I’ll find the scoundrels there.

“Well, be careful in the meantime. We don’t want you getting sick,” he said, but, taking her pencil, he wrote on the other side of the napkin.

Tread lightly. Corruption and backstabbing everywhere.

“Thank you for that advice. You’re right, of course. Um, would you pass the wine?”

The Tula Arms Plant, Mia learned, had transported its primary manufacturing beyond the Urals during the German invasion and left only one division in local operation. Nonetheless, when she arrived at its single remaining factory, she found a storm of activity.

The plant foreman met her at the entry gate, presumably after a telephone call from Ustinov. A haggard man in need of a shave, he could have been anything between forty and sixty. He was friendly and garrulous, and seemed to relish the idea of showing her around.

“So, what do you mostly do here?”

“Everything for the front, everything for victory is our motto, though in fact, our larger guns are produced in the east. This plant makes and refurbishes small arms, that is, the SVT-40 self-loading rifle, Nagant revolvers, Tokarev pistols, and the Mosin-Nagant 91 / 30 sniper rifle.”

“I understand you receive many of the parts from the United States.”

“Yes. A lot of the steel comes from there, as well as the metal jackets for the shells.”

“Are you well supplied? I mean, do you ever have to slow production for lack of materials or a late delivery?”

“No, the parts deliveries are always sufficient and on time. The factory operates twenty-four hours a day, in three shifts, so if we ran out of a part, it would bring the whole operation to a halt. You are welcome to visit the factory floor, if you wish.”

The “floor” consisted of a seemingly endless row of tables set end-to-end, with workers on both sides assembling parts drawn from wooden crates behind them. Almost all were women and old men. The clatter of metal against metal set up a sort of white noise, pierced occasionally by someone shouting.

She approached closer and peered over the shoulder of a woman as she oiled and fitted a spring into a magazine clip for one of the rifles. The woman’s hands were bony and weathered, and every crease and fingernail was black. Mia could not see her face, but even from the rear it was obvious how gaunt the woman was. Her work smock was filthy, too, though cleanliness was probably of a very low priority in such a factory. Not to mention the scarcity of soap. Still, it made her cringe.

She returned to the foreman, who waited for her at some distance. “May I see the end of the production line, too?”

“Of course. That will be at the far side of the hall, where they attach the scope.”

Two other women, equally malnourished, worked on the scope, one attaching it and the other measuring its accuracy. She held it up to her eye and pointed it toward a cardboard grid, then handed it back for adjustment. After two or three of such adjustments, number-one woman passed it to the final table, where an old man attached a cloth strap to rings on the nozzle and stock. Then he laid the rifle in a wheeled crate next to others. When the crate was full, a young boy wheeled it away.

“It all seems very efficient, though I’m sure it’s exhausting.”

“Everything for the front, everything for victory,” he repeated. “That’s what keeps us going.”

Mia couldn’t tell how much of his reaction was genuine patriotism and how much propaganda. She knew about the sacrifices on the battlefield but had never imagined how hard life also could be in the factories.

“Can you show me the canteen?”

“If you wish,” he said, and led her along a corridor and down the stairs to a basement. She checked her watch, seven in the evening. “When do the workers get dinner?”

“A hot meal is served every eight hours, at five thirty, thirteen thirty, and twenty-one thirty. That is, at the beginning of the shift for some people and at the end of the shift for others. The food is whatever the commissariat has provided that week.”

“What does the commissariat usually provide?” She recalled an enormous shipment of Spam, powdered eggs, and sugar on the list from the depot at Arkhangelsk. It had been signed for ten days before.

“Kasha, mostly. And bread. Though the delivery is late this month. And the last delivery of flour was only half. Nobody explained why. We’ve had to cut the rations for the last three months.”

“Do you have meat?”

“A little horse sausage, but that was last month.”

“I mean the American Spam. Recently.”

“No. No. Nothing like that. Not since I’ve worked here.”

“I see. Well, thank you for taking the time to show me around. I won’t bother you any longer. I have a train to catch, so I’d better start for the station. Please, take these as a token of my thanks for your help.” She tapped out four cigarettes from her pack and presented them. For the first time, he smiled.

They shook hands and she left, suspicion crackling in her head.

Mia sat fretting on the return train to Moscow, not only about the information she had just obtained and which would surely have ramifications, but about her arrival. Robert had agreed to be at the Moscow station when the train from Tula arrived, but they had been sidelined twice while a troop train and an industrial train had claimed track priority, and now they were pulling into Moscow station over two hours late. Would he wait?

But as she descended from the train into the cold mist of the station platform, a different figure came forward to greet her.

“Colonel Nazarov? What a coincidence.” She accepted his gloved handshake and tried to look past him. “I was just about to search for my driver.”

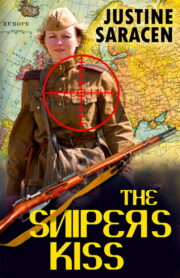

"The Sniper’s Kiss" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "The Sniper’s Kiss". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "The Sniper’s Kiss" друзьям в соцсетях.