Hopkins tapped off the millionth ash of his millionth cigarette and smiled ambiguously. “Not quite yet. It’s true that Truman ended the program officially on May 11, but Stalin was so angry, it looked like it would affect postwar talks. So I’ve got to go over there and work out a compromise. An extension, with limited provisions, at least through the summer.”

Mia nodded. Where was this leading?

His smile widened. “You ready for one more round with Uncle Joe?”

“Me? Meet with Joseph Stalin?” She was speechless.

“Yep. Six meetings, starting on May 26. Harriman’s also coming, to discuss China, Japan, the Control Council for Germany, Poland, the United Nations, all that kind of thing.”

Mia stared into space for a moment. Return to Moscow, where she’d suffered the greatest joys and worst torments of her life? Where the woman she loved might be within reach, but also the man who wanted to kill her?

“Ready when you are.”

Hopkins, with Mia at his side taking notes, labored through the six meetings, placating Stalin. It seemed to her they’d given up a lot, but they still needed Stalin’s goodwill to work on the United Nations, to continue against the Japanese, to plan the agenda for the reconstruction of Germany.

She dared not bring up the subject of Alexia and the Gulag, had no idea even of how to approach it with Hopkins. Against the magnitude of the negotiations, it seemed presumptuous, not to say ludicrous, to plead for the life of a single woman.

The meetings she attended were tense, and she sensed the waning of goodwill of both Hopkins and Harriman in the face of Stalin’s demands—demands they would have to meet.

But after the final session, with typical Russian bonhomie, Stalin slapped Hopkins on the back and announced a victory dinner in the Catherine the Great Ballroom.

The banquet was pure Russian and included the entire Politburo, the top echelon of military leaders and commissars, and Moscow’s inventory of ambassadors of other countries. For Hopkins, who had already said in private that he was “on leave from death,” it was obviously a test of endurance.

Mia was glad the fighting was over and that Hopkins had wrung at least a few concessions from Stalin, but her personal bereavement remained unchanged. Molotov made no eye contact with her during the evening, but she sensed his cold presence. He was being lionized by the great dictator and applauded by the entire company, and she hated him for it.

She drank with restraint, as Hopkins did, though out of bitterness rather than sickness. By the end of the evening, which was in fact nearly morning, she and Hopkins were two of the very few people in the Catherine the Great Hall still sober.

As the guests began to stagger away, she saw that Hopkins was in a conversation with Ustinov and showed no sign of leaving. Catching his eye, she signaled that she would meet him later at the embassy car outside and left the hall.

The victory banquet would be the last hurrah before the return to Washington to face multiple terminations. Harry Hopkins would retire from White House service, Lend-Lease contracts would expire, and she would soon have to find other employment. The Kremlin visits would simply be memories colored forever by the images of a stunning Kremlin guard she’d fallen in love with. She regretted bitterly that she had no photo of her and nothing she could use but her name to track her down one day.

For that matter, she’d have to memorize Moscow and the Kremlin as well. Would she be allowed to explore the Kremlin Palace a little before their departure?

The adjoining great halls were open, and she crept as inconspicuously as possible from one to the other. She could not help but be both appalled at the extravagance of the tsars and impressed by their art.

“So, you are the one,” a rough voice said behind her. She froze, as if caught in a crime, wondering who had snagged her. Chagrined, she turned around.

Joseph Stalin stood in the doorway smoking his pipe.

Mia was confused. “‘The one,’ sir?”

“Yes, the one who helped my foreign minister Molotov uncover the corruption in the factories. That we punished severely and without hesitation.”

Mia forced a smile. “Yes, sir. That was me.”

“And you were also the object of a certain remark President Roosevelt made to me. On behalf of his wife, he said.” The dictator puffed a moment on his pipe and blew the smoke out of the side of his mouth.

She was puzzled. What had she to do with President Roosevelt or the First Lady? He continued puffing on his pipe as he strolled past the ornate walls and furniture without bothering to look at them, like someone’s uncle who’d been talked into visiting an art gallery he didn’t care about.

“A good man, your President Roosevelt. This Truman fellow, I don’t think he’s made of the same stuff.”

“It’s hard to say, sir. He’s only just started.”

Stalin shrugged. “Maybe. But I was fond of Mr. Roosevelt. He always wanted to talk ‘man to man,’ as if no one else was in the room but us.”

“He valued the personal touch.”

“Yes, the personal. It’s easy to forget the personal when you’re conducting a war. You get used to moving armies around, issuing orders that will cost thousands of lives—those of your people or the enemy, sometimes both.”

Mia thought of the endless purges.

“Did you know, we lost about a million people in Stalingrad alone? But it couldn’t be otherwise. Stalingrad had to be held, even if it took a million dead to hold it. If I had thought about the suffering of any one soldier and held back, we’d have lost the city and perhaps the war.”

Where was he going with this? Why wax philosophical to her, a foreigner and a capitalist? He had no idea she’d been one of those soldiers he didn’t care about.

“You have to harden your heart, ignore loyalties, the urges of friendship, and concentrate on annihilating the enemy at whatever cost. Ultimately, a father knows what is best for his children, and they must obey.”

She cringed inwardly, at the same outrageous words she’d heard her father say. She was also aware of how he could bend and twist the word “enemy” and strike at the heart of the people he was ostensibly defending. Curiously, she was not afraid of him.

“And yet, Marshal Stalin, doesn’t the personal intrude now and again? After all, we’re not automatons, not even a field marshal moving armies. We’re flesh and blood, and we love.” She realized with a shock that she was arguing with Joseph Stalin and fell silent.

He seemed not to notice her insolence and puffed again, blowing smoke again from the side of his mouth. “Yes, I remember love. It was a very long time ago. A dangerous indulgence.”

Finally he took the pipe from between his teeth. “In any case, the ‘personal’ is not really my style. I’m not in the habit of granting personal favors, least of all to foreigners.” He pointed the mouthpiece of his pipe at her, as if to hold her attention. “But this was a man I admired.”

“He asked you for a favor, sir?” She hoped he’d get to the point soon.

“Yes, and it is also curious that this favor was identical to the one requested by Major Pavlichenko. I might almost think it was a conspiracy.” He chortled, and she wished she could shout, “What the hell are you talking about?!”

“But a great man has died before he could see the fruits of his labors.” Stalin walked another few paces, looking everywhere but at her. “So, out of respect for his memory, I will grant this one request, strange as it is. Good evening to you.” With a brief nod in her direction, the dictator of the Soviet Union exited the room, letting the fifteen-foot door close behind him.

She stood, speechless, still at the center of the great chamber, a bundle of confusion in a dark dress in the midst of splendor.

The creak of another door opening drew her attention. Molotov stood in the entrance of the neighboring stateroom and beckoned her.

Molotov, her archenemy. Yet in the wake of Stalin’s little speech, he seemed harmless. She crept cautiously toward him, and as she reached the door, he stepped aside, revealing another person seated on a chair behind him. Mia entered, incredulous.

Alexia stood up. She wore a fresh uniform, though it was stripped of insignia, medals, and rank. Her face was thin, not yet gaunt, though lack of facial fat accentuated the muscle around her mouth. Her hair was shorter than it had been, and not shaped, as if it had grown untended. Her gray eyes shone as she smiled weakly, then glanced anxiously at the foreign minister.

“By order of the boss,” Molotov said dismissively, as if her release meant nothing to him. He slapped an envelope into her hand. “Here’s her exit visa. Now get her out of the country and out of my sight.”

“Just like that? She’s free?” Mia stammered, taking the first steps toward Alexia.

Molotov’s face grew hard. “On this condition. Not one word. Not the slightest hint to the press about our arrangement and its history. And if you believe you can break this agreement once you are in your own country, let me disabuse you. We have men in Washington who will be watching, reading your newspapers. If this story appears, something very bad will happen to you. Immediately.”

She was certain his threat was real. “Do Mr. Hopkins and Mr. Harriman know about this?”

“I presume the boss is telling them now. What they do about it is no problem of mine. Her name is removed from the military records. Just take her out of here.”

He did an about-face and strode from the hall.

Chapter Thirty

Five days later, Mia and Alexia stood together among the spring blossoms in the Rose Garden.

“So this is the White House,” Alexia said. “I hadn’t expected it to be so simple.”

“Compared with your tsarist palaces, I suppose it is. But then, we didn’t have five hundred years of autocracy flaunting its wealth.”

“Your head of state is now…?”

“Harry Truman. Much less scary than yours. He’s less inclined to execute people who disagree with him. I wish I could have brought you back to more stability, but everything changed all at once. The war in Europe ended, Mr. Roosevelt died, and my job has almost finished. I’m at loose ends myself.” She touched Alexia’s hand lightly, not daring to hold it. “But I’m sure it’s much worse for you.”

“Yes. I feel like I’ve leapt a great chasm and that I’m still in mid-leap.”

Mia turned to face her directly, smiling at the new hairstyle. “Are you having any regrets yet?”

“Many of them. That I was not kinder to the friends I lost. That I wasn’t present when my grandmother died. That I wasted so much time as a Kremlin ornament rather than as a soldier. But no regrets about coming home with you, my dear Demetria. None at all.”

Mia began strolling again. “Well, the US is not paradise. We have our own problems. Negroes still don’t enjoy the ‘freedom’ we’re all supposed to have, and people like you and I must still live in secret.”

“But at least we don’t have to fear labor camps or execution,” Alexia said.

“No. No execution. And can you feel it? That both our countries are changing? Perhaps one day, before we’re too old, we can return to a kinder Russia without Stalin, and locate Kalya and Klavdia.”

“Yes. That’s something to look forward to.”

“In the meantime, you have a job at Georgetown, thanks to Miss Hickok, and we have a sunny room in a boardinghouse until we can get our own apartment. I still have to tie up the loose ends of Lend-Lease for Mr. Hopkins, so I’m employed for another month. After that, we have our whole lives to do what we want.”

“And you’re still allowed in the White House?”

Mia laughed. “Don’t worry. Mr. Truman has given me all the time I need to transfer my records to Mr. Hopkins’s Washington office and move my belongings from my room.”

“So we can sleep there tonight? That’s good. I want to be able to say one day that we made love in the White House.”

Mia snickered lewdly at the thought. “We’ll have to do it quietly, you know.”

Alexia brushed one shoulder against her. “We can be quiet. We’re snipers, remember?”

Postscript

World War II: September 1939 (invasion of Poland) to September 1945 (surrender of Japan.) The US supplied its allies with war material from August 1941 but sent troops initially to Asia in 1942. The first frontal assault on occupied Europe was not until June 1944, and the Soviet Union, by far, suffered the most casualties. Wikipedia estimates: USA: 420,000, England: 451,000, France: 600,000, China: 15–20 million, Soviet Union: 27 million. Recognition of Soviet casualties and victory in Berlin makes it all the more disturbing that many Americans today do not know that Russia was an ally and believe that the US won the war.

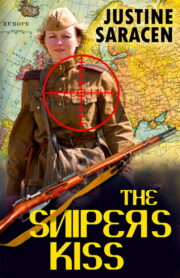

"The Sniper’s Kiss" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "The Sniper’s Kiss". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "The Sniper’s Kiss" друзьям в соцсетях.