Marchisa curtseyed and left. Geoffrey took Alienor’s hands and his lips touched her knuckles. They exchanged a wordless glance, and then he bowed and followed Marchisa outside.

For three more nights, as she recovered, Alienor had the eagle dream. It was always a jolt to awaken and find herself in the dark confines of her tent rather than soaring above the world, but each time the dream came, she felt stronger and more sure of herself. Louis had still not visited to see how she fared, although he sent messages via Geoffrey, who visited Louis’s daily councils and reported back to her.

‘The King is delighted you are recovering and glad that his daily prayers for your wellbeing have been successful,’ Geoffrey said with the neutrality of a polished courtier.

Alienor raised her brows. ‘How gracious of him. What else?’

He gave her a questioning look. ‘About you?’

She shook her head. ‘I doubt there is anything I want to hear on that score from his lips. I meant what news of Constantinople?’

Geoffrey’s mouth turned down at the corners. ‘The King has still heard nothing from the lords he sent as heralds. The Emperor’s envoys say all is well and our men are preparing for our arrival, but we have no news of our own. They could be dead for all we know.’

‘We should consider this carefully.’ Alienor paced the tent. ‘If we are to deal with the Greeks successfully, we must be as cunning as they are, and know their ways. We must learn from them everything we can.’

Geoffrey rubbed his hands over his face. ‘I dream of Gençay and Taillebourg. The harvest will recently be in and the woods full of mushrooms. My son will have grown again, and Burgundia will have made me a grandfather by now.’

‘You are not old enough to have grandchildren!’ she scoffed.

Wry humour deepened the lines at his eye corners. ‘Sometimes I feel that I surely am,’ he replied.

She put her hand lightly on his sleeve and he clasped it briefly in his own before releasing her and going to the tent flaps. Outside, one of Louis’s senior squires was dismounting from his palfrey. He bowed to Geoffrey, knelt to Alienor and said, ‘The King sends word that Everard of Breteuil has returned.’

Alienor exchanged looks with Geoffrey. De Breteuil was one of the barons Louis had sent into Constantinople. His return meant news.

Geoffrey called for his horse.

‘I shall attend,’ Alienor said.

He eyed her dubiously. ‘Are you well enough? If you prefer to remain here, I can report to you later.’

Alienor’s eyes flashed. ‘I shall appear in my own capacity and hear matters as they are discussed here and now.’ She swept her shoulders into the cloak Marchisa was holding up behind her and fastened the clasp with decisive fingers. ‘Do not seek to put me off.’

‘Madam, I would not dare.’ He delayed mounting his horse to help her into the saddle of her grey cob, and plucked her eagle banner from the ground in front of her tent to bear as her herald. ‘It is always an honour.’

She firmed her lips. Her anger continued to simmer. She was a match for all of them but had to fight every inch of the way to be recognised and accorded her due, sometimes even with Geoffrey, who was one of the best.

The army had spread out over a mile: an assemblage of ragged tents, flimsy shelters, horse pickets and cooking fires. In the pilgrim camp, women stirred grains and vegetables in cooking pots, or ate meagre portions of flat bread and goat’s cheese. One sat suckling a newborn baby, conceived when its parents had had a roof over their heads and the security of mundane daily labour. If it survived the journey, which was unlikely, it would be forever a blessed child, born on the road to the Sepulchre. Some women were showing pregnancies that had been conceived along the road. Many pilgrims had sworn oaths of celibacy but had given in to temptation, while others had preferred to remain unsworn and sow their wild oats in the face of death. Alienor was glad Louis had taken such a vow, for she could not bear the thought of lying with him.

Riding into Louis’s camp, she saw the looks of consternation from his knights and felt a glimmer of satisfaction. The falcon of her dream was flying over her and she felt strong and lucid.

Louis was stamping about the tent, hands clasped behind his back, jaw tight with irritation. His commanders and advisers stood in a huddle, their expressions grim. At their centre stood the newly returned baron Everard de Breteuil, a cup in his hand. An angry graze branded his left temple and grey hollows shadowed his cheekbones. Louis’s chaplain Odo of Deuil sat at a lectern, writing furiously between the lines pricked out on a sheet of parchment.

Louis looked up at Geoffrey’s arrival. ‘You took your time,’ he grumbled. His gaze fell on Alienor and his nostrils flared as he drew a sharp breath.

‘I have come to hear your news, sire, since it must surely affect us all,’ Alienor said, pre-empting him.‘It will save you coming to tell me yourself.’ She went to sit on a low curved chair in front of the screen that concealed Louis’s bed, making it clear she was here to stay. ‘What has happened?’

Louis’s brother Robert of Dreux answered. ‘We were meant to rendezvous with the Germans tomorrow, but they have already embarked across the Arm of Saint George.’

‘That wasn’t the plan; we were supposed to join them first,’ Louis said.

‘Komnenos would not allow the Germans to enter the city,’ de Breteuil explained. ‘They were confined to his summer palace outside the walls and food was brought out and sold to them. Komnenos refused to go to the German camp and Emperor Konrad would not enter Constantinople without his army. Each fears treachery by the other.’

Odo of Deuil muttered something over his lectern about what could you expect from Germans and Greeks.

De Breteuil took a swallow of wine. ‘The Germans were ordered to cross the Arm and so were we. When we declined our food supplies were cut off and we were harassed and set upon by infidel tribesmen – while the Greeks stood by and did nothing. At one point I thought we were all going to die.’ He touched his grazed temple. ‘When we sent a deputation to the Emperor, he claimed to have no knowledge of this and said he would set it right, but he was lying. He must have given the order to stop our food, and he did nothing to prevent the infidels from attacking us. He has made it clear we are as a plague of locusts to him, yet he wants us to do all the fighting and dying while his troops look on and pick their nails.’ De Breteuil’s mouth twisted. ‘We are being used, sire, and by men who are no better than infidels themselves. The Emperor has made a twelve-year truce with these tribes who attacked us. What kind of Christian ruler does that?’

‘But whether we like it or not, we need the Greeks to see us safe across to the other side with plentiful supplies and equipment,’ Alienor spoke up. ‘We must continue to speak the language of diplomacy.’

Louis gave her a cold look. ‘You mean the language of deceit and treachery, madam?’

‘I mean that which they regard as civilised. They treat us as they do because they see us as barbarians, with neither subtlety nor finesse. I do not say this is the truth of the matter, I say that this is how they perceive us, and if we are going to make any headway at their gates, it will not be by banging our shields upon them.’

Louis drew himself up. ‘I am the sword of God,’ he said. ‘I shall not veer from my path.’

Odo of Deuil nodded in the background and scribbled down Louis’s words.

‘No one is asking you to,’ Alienor said with weary impatience. ‘Water wears away stone, no matter how solid. And it pours through the smallest crevices. We must be as water now.’

‘And you would know?’ Louis said with contempt.

‘Yes,’ she said. ‘I would.’ She rose and went to the tent entrance. It was fully dark now and the campfires glimmered at intervals like giant fireflies caught on a spider’s web. She looked at Louis over her shoulder. ‘We need to rest, and we need to garner supplies. You might forgo those things because you distrust the Emperor of the Greeks, but if you were to conciliate with him, think of what you might gain that Konrad of Germany has not.’

‘And what would that be? Why should I wish to clasp the hand of a man who agrees truces with infidels and sets them on my men?’ Louis asked with a curl of his top lip.

‘You travel this road not just as a warrior, but as a pilgrim,’ Alienor said. ‘Think of all the churches and shrines in Constantinople that Konrad has not seen. Think of the precious relics: the crown of thorns that pierced Our Lord’s brow; a nail of the crucifixion stained with His precious blood. The stone that was rolled away from His tomb. If you are desirous of seeing and touching these things, it behoves you to deal with their guardian, whatever your opinion of him.’ She waved her arm, and her full sleeve wafted a scent of incense. ‘Of course, if you do not care for such things, and to have such advantage, then go on your way with your sword in your hand.’

A muscle flexed in Louis’s cheek but he remained silent.

‘The Queen makes a good point,’ said Robert of Dreux. ‘We shall have greater prestige than the Germans. You can have words with the Emperor about the treatment of our men and make a diplomatic triumph out of this that will add to the glory of France.’

Alienor deemed it prudent to leave then. Geoffrey would remain as her eyes and ears. She knew Louis would acquiesce, but not in her presence, because he would never agree openly with her point of view. He was a fool who could barely find his hindquarters with his hands.

28

Constantinople, September 1147

The great citadel of Constantinople occupied a triangle of land bordered on two sides by the sea and enclosed within great walls. On the eastern side of the city, and within another enclosure, its right flank was guarded by a stretch of water known as the Arm of Saint George. A massive chain protected the end of that stretch, preventing ships from sailing up the wide estuary and attacking the city walls.

On a hot morning in September, the French army arrived before its walls and set up camp. Alienor exchanged the grey cob that had borne her all the way from Paris and mounted instead the spirited golden chestnut palfrey sent to her by Empress Irene. His coat had a metallic gleam and his gait was like the smoothest silk, hence his name: Serikos, which was Greek for the cloth. Louis too had been presented with a horse: a stallion with a coat that glittered like sunlit snow. Both mounts were glossy and well nourished, unlike the crusader horses, which had lost condition during their hard journey and were unsuited to the parching heat of the Middle East.

Alienor rode beside Louis, her head up, her spine straight. She wore a gown of coral-red samite stitched with pearls. The coronet set over her silk veil was a delicate thing of gold flowers studded with sapphires. Louis was more sombrely clad in a tunic of dark blue wool, but he wore a jewelled belt, rings on his fingers and a coronet. After a single glance, Alienor did not look at him again, because she could not bear to see the gaunt, tight-lipped man riding in the place of the smiling youth who had once taken her hand and looked at her with his heart in his eyes.

They were greeted by nobles of the Greek court, their colourful silk tunics worn with the casual ease of everyday garb. In France only magnates could afford such fabric and even then it was a rarity. Despite their own efforts to appear magnificent, Alienor knew they must look like creased and shabby barbarians to the Greeks, and reinforce their jaundiced view of Christians from the north.

They were escorted to the imperial Blachernae Palace, parts of which were still under construction. Cages of scaffolding enclosed sections of wall and labourers toiled, hoisting hewn blocks of stone and buckets of mortar on to the working platforms. The clink of chisel on stone, the creak of the winch wheel and the shouts of the labourers caused a permanent clamour. However, the main palace was complete and faced with decorated arches worked in marble and patterned with different-coloured bands of stone.

Servants came running to take their mounts and escort Louis and Alienor to the portico of the palace where Emperor Manuel Komnenos waited to greet them, together with his consort, the Empress Irene. Manuel was of Louis’s age and stature, but there the similarities ended. Manuel resembled a fabulous mosaic, his robes of royal purple so heavily encrusted with gems that they were as stiff as a mail shirt, and when he moved, he glittered. He was dark-haired and dark-eyed, and bore himself as if he were a deity condescending to supplicants. Beside him, Louis looked insipid: a lesser being caught blinking in the Godlight.

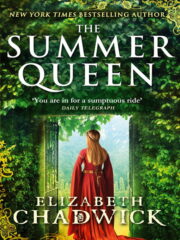

"The Summer Queen" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "The Summer Queen". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "The Summer Queen" друзьям в соцсетях.