The elderly churchman coughed and took a drink of his wine. ‘You must see to the christening of your new daughter,’ he said. ‘You have decided on a name?’

Louis hadn’t. All his focus had been on a son. He certainly wasn’t going to change the name to Philippa even though it was in both families. ‘I leave that to my wife,’ he said. ‘She bore her. Let her have the naming.’

36

Abbey Church of Saint-Denis, February 1151

Alienor signed her breast and rose from her prayers, her breath clouding the air. Saint-Denis was bone-cold on this bleak February morning. The swords of light piercing the high windows to strike the tiled floor imparted no warmth. The only heat in the church came from the rows of votive candles flickering on their stands. Alienor paused to light one and place it beside the others.

Suger had been in his grave for several weeks. Saint-Denis had tolled a knell for its beloved abbot as he was laid to rest in the church he had glorified for so much of his life. He had died in fear for his mortal soul – afraid that he had spent too much time on politics and dealings with the world instead of attending to spiritual matters. He had begged Bernard of Clairvaux to attend his deathbed and pray for him, but Bernard, old and frail himself, had been unable to come, and instead had sent him a linen kerchief, which Suger had been clutching when he died, begging for constant masses and prayers to be said for his soul.

It was strange, Alienor thought. She had known Suger all the years she had been Queen of France. She had often found him obstructive and irritating. He could be devious in obtaining his own ends, but she had never felt any personal malice coming from him, and that raised him in her estimation. He had not allowed his private opinions to colour his politics. Louis had wept like a child for his tutor and mentor. Nevertheless, when his tears dried, his eyes were hard.

She returned to the guest house where she was staying before her return to Paris. She had letters to write to various vassals and members of the clergy. Suger’s death had been an ending and a beginning, but the latter was suspended in that moment following the resonance of the final note. Last night she had dreamed of Poitiers; a warm, thyme-scented breeze had brushed her eyelids, lifted her hair, and filled her with yearning.

Louis had not joined her at her prayers, preferring to hold his own separately, but waited for her now, his plain dark robes embellished by a gold reliquary cross on his breast. He was pale and hollow-cheeked, and he made her shiver. She acknowledged his presence and put distance between them as swiftly as she could. They had barely spoken to each other or shared company since the birth of their second daughter, whom Alienor had named Alix. She had borne her in early June and emerged from confinement at the end of July. She had handed Alix to a wet nurse on the day of the churching and her fluxes had begun again in early September. Louis had not visited her chamber to sleep with her and she had not encouraged him. Their marriage was as bleak and joyless as this raw February morning.

‘I wish to talk to you about annulling our marriage,’ Louis said. His mouth had a sour down-turn.

Alienor raised her brows. ‘As I have suggested to you many times before, but it has never come to fruition.’

‘It will do so this time, I shall make very sure of it.’

‘So you can make another match and beget a son?’ She gave him an acerbic smile. ‘Perhaps you are only destined to have daughters, Louis. Have you thought about that?’

A muscle ticked in his cheek. ‘That is not so. Our match, whatever the Pope decreed, is consanguineous and a sin in the eyes of God. It is not meet that we should stay together.’

‘You knew it was consanguineous on the day you married me.’

He flushed. ‘I did not; I had no inkling.’

‘But Suger did; he knew very well, but nothing mattered save that Aquitaine be delivered to France. Many couples related in the fourth degree as we are live their entire lives married, and they are blessed with sons. Consanguinity is but a useful excuse on which to hang a parting.’ She opened her hands. ‘I am delighted to agree to an annulment, Louis, but if you had consented to my request in Antioch, you would have saved us three years of wasted time.’

He scowled. ‘Antioch was a challenge and an insult to my kingship. I was prepared to grant your annulment when we came to Tusculum, but the Pope judged otherwise. I did my best, but clearly he was in error, and we must part.’

Alienor felt a rush of relief, but there was also a bitter taste in her mouth, and a stultifying sense of futility. She had not wanted to marry Louis, but once it was done, she had believed they could make a working partnership, and that the glint of attraction might become something deeper. Instead, the machinations of others had warped and twisted the relationship until it became untenable. To come to this point felt like failure. Yet it was a release too. There would be many months of negotiation ahead, but let the decision be made and let consanguinity be the coverall excuse, even if they both knew it was not the true reason. ‘Well then, if you can convince the Pope to reverse his decision, let us go forward.’ She gave him a hard look. ‘Of course you will no longer have a governing say in Aquitaine. You must remove all of your officials and garrisons from my territories.’

‘That will be attended to,’ Louis said curtly. ‘But our daughters are still your heirs, so I have an interest on their behalf. They shall remain with me and be raised in my household.’

Alienor hesitated for a moment, and then acceded. What did she have or know of her daughters anyway? Marie had been barely walking when Alienor had gone to Outremer, not returning to France for three years. Alix was a babe in arms. Neither daughter knew her, nor she them. All she could feel was a sense of loss and regret for what might have been.

‘Then we are agreed,’ Louis said. ‘I shall set matters in motion.’ With a stiff nod, he left the guest chamber. Alienor gazed at the door as he closed it behind him. She felt numb when she should have felt like an eagle set free from the mews. Having been constrained for so long and having striven to escape until her wings were battered and her spirit close to breaking, she needed time to prepare herself for flight and gain the courage to soar.

She could have Geoffrey now, but everything had changed. She could return to Poitiers and feel the warm wind in her hair, but she would be a different person. When innocence was gone, one’s life pattern changed forever. With Aquitaine no longer united with France, she had to find new strategies and policies to survive.

There was much to do, but today was a time for evaluation. Tomorrow she would begin.

37

Castle of Taillebourg, March 1151

Geoffrey de Rancon looked at the letter in his hand and then at the Archbishop of Bordeaux. Outside a strong March wind blew fluffy white clouds past the turret window of Taillebourg’s great tower overlooking the Charente River. The day was chilly enough to warrant a good log fire in the hearth, but held that promise of spring.

‘Our duchess is coming home,’ Geoffrey said, and felt a lightning spark somewhere deep inside him. The pity was that she had ever had to leave.

‘Yes,’ said Gofrid, ‘but not until the autumn, and even then the annulment will not be secure until well into the next year.’

‘She says Louis has found three bishops to pronounce the annulment,’ Geoffrey said. ‘But will the Pope agree?’

‘I think he realises there is nothing more he can do,’ the Archbishop replied, ‘and that beyond this point, concessions must be made. It is not as if either party is contesting the matter, or has a previous spouse in the background.’

Geoffrey dropped his gaze to the piece of parchment and the elegant words of a scribe informing him that Louis and Alienor would be here in the autumn to tour their lands and take stock. French soldiers and officials were to be withdrawn during the visit and part of Geoffrey’s brief was to find men of Aquitaine to fill the positions. There was a separate note to him from Alienor, written in code, telling him that the autumn could not come soon enough and that the only thing that filled her with hope each morning was her return to him. She had written ‘Aquitaine’ but he knew it was a substitute for his name. He did not want to let her down, yet he feared it was already too late.

The Archbishop was watching him with shrewd eyes. ‘It will be a difficult time,’ he said. ‘Our duchess is a strong-willed woman, but nevertheless she will be a woman alone. She will need guidance and many will try to take advantage.’

Geoffrey returned the Archbishop’s look steadily. ‘Not if we are here to protect her. I will defend her rights as duchess with my life.’

‘Indeed. You are an honourable man and you will do the right thing.’

Geoffrey said nothing because he could not tell how much the Archbishop knew, or how much of an ally he was. He suspected they were both fencing in the dark. When Alienor returned to Aquitaine as duchess in full, she would need courtiers and clerics to advise her, and it was only wise to secure those affinities before she arrived.

The Archbishop sighed. ‘I had hoped for great things of the marriage between the King of France and our duchess, as did her father. It was his ambition that his daughter should be the matriarch of a great dynasty. How could we have known that it would come to this?’

‘Indeed,’ Geoffrey said, and then fell silent, because there was nothing else to say. He pinched the bridge of his nose, feeling tired and dull. It was as if he was a fading footprint in the dust, rather than the man striding forward to make his destiny.

There was sickness in the palace. People were succumbing to high fevers accompanied by sore eyes, congestion and an itchy spotted rash. Both of Alienor’s daughters had caught it, as had their Vermandois cousins, and the nursery in the royal palace was full of sick, fractious children. Louis contracted the fever as he was preparing to go to war in Normandy against the young Duke Henry and his father Geoffrey of Anjou. On the day he should have set out to join his army and liaise with Eustace of Boulogne, who was already in the field, Louis was in bed, sweating and shivering in delirium. Beset by terrible dreams in which Abbé Suger threatened him with the fires of hell, terrified of dying, he sent for his confessor and had his attendants dress him in sackcloth. It became clear he was not going to recover in a day or even a week, and that the battle campaign – a major strike against the city of Rouen – would have to be postponed.

‘Louis has decided to call a truce,’ Raoul told Alienor and Petronella when he came to see how the children were faring. ‘He cannot lead an army into Normandy in his condition, and there is no telling how long the contagion will last.’

Petronella turned her head away from her husband and refused to look at him, her attitude one of angry rejection. She wrung out a cloth and laid it across her son’s flushed forehead. The little boy whimpered and began to cry.

Alienor looked at Raoul. ‘How is the truce to be arranged?’

He cast an exasperated glance at his wife. ‘The Count of Anjou and his son are to come to Paris to discuss the situation and agree a cessation of hostilities in return for certain concessions.’

‘Such as?’

‘Louis will recognise Geoffrey’s son as Duke of Normandy in return for their giving up the territories in the Vexin that they hold.’

‘And he thinks they will agree?’

Raoul shrugged. ‘It will be to their advantage. The King is too sick to campaign against Rouen, and has too many other issues to deal with to start another campaign when he has recovered. If he can arrange a truce until next year and gain some land into the bargain, all to the good. The Count of Anjou and his son, for the exchange of a strip of territory, will buy valuable time to deal with their own concerns.’ He gave a half-smile. ‘I am too old a warhorse to be disappointed that we are not riding out on campaign. It will suit me to sign a truce.’

Alienor absorbed the detail that she had better prepare to receive guests, and calculated how long she would have before their arrival. Even if Geoffrey of Anjou was a rogue and far too full of his own masculine dazzle, he would be a distraction from her cares. His son she had never met, although she had heard tales about his precociousness and fierce energy.

Raoul looked at the children. ‘I will go and say my prayers for them,’ he said. ‘There is little else I can do here. Petra …’ He went to touch his wife’s shoulder and she shrugged him off.

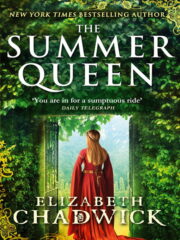

"The Summer Queen" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "The Summer Queen". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "The Summer Queen" друзьям в соцсетях.