As they rode side by side into the City, he told her that the King was in the Palace of the Tower and that the coronation would be on the twenty-fourth of June. It was now the fifth so there was not much time.

There was a great deal to tell Anne but he did not want to overwhelm her with the detail of events nor did he wish to alarm her. He could see that she was uneasy when she heard that the Queen was in Sanctuary.

He took her to Crosby Place, his residence in London, and as soon as she arrived he insisted that she rest. He sat beside her bed and talked to her, explaining how the Woodvilles had tried to get control of the King, that their ambitions had to be curbed and it was for this reason that he had had to imprison Lord Rivers and Lord Richard Grey. The King was not very pleased about this.

‘You see, Anne, they have brought him up to be a Woodville. My brother was too easy-going. He allowed the Queen to surround him with her relations. They have taught him that they are wonderful, wise and good.’

‘Does it mean that he turns from you?’

Richard nodded ruefully. ‘But I shall change that. He will learn in time.’

‘I do wish there need not be this conflict,’ said Anne, ‘and I wish that you could come back to Middleham.’

‘It will be some time before I do, I doubt not. My brother left this task to me and I must fulfil it.’

Then he talked of Middleham to soothe her and he asked about their son’s progress with his lessons, for he was clever and his academic achievements made a happier subject than his health.

Anne slept at last and as Richard was leaving her chamber one of his attendants came to tell him that Robert Stillington, the Bishop of Bath and Wells was below and urgently seeking a word with him.

Richard immediately commanded that the Bishop be brought to him. He bade him be seated and to tell him the nature of this important news.

Stillington folded his hands and looked thoughtful. After arriving with a certain amount of urgency he seemed reluctant to explain the cause of his visit.

Richard knew that he was one of those ambitious men who sought advancement through the Church. There were plenty of them about. He had been a staunch Yorkist and in 1467 had become Lord Chancellor, an office of which he had been deprived on the restoration of the House of Lancaster; but it was given back to him when Edward returned. He resigned after a few years and when Edward had been a little disturbed by Henry Tudor’s bombastic claims, Stillington had been sent to Brittany to try to persuade the Duke to surrender him to Edward.

He had failed and later he had been put into the Tower at the time of Clarence’s death on a matter which had been somewhat secret and of which Richard was ignorant. It had seemed too trivial at the time to enquire about and Edward had dismissed it. In any case Stillington had soon been released.

Now here was Stillington with this urgent news which he prefaced by explaining it was for the ears of the Duke of Gloucester alone, for he himself did not know what use should be made of it.

All impatience Richard urged him to explain and Stillington burst out: ‘My lord, the late King was not truly married to Elizabeth Woodville.’

Richard stared at him in astonishment.

‘Oh my lord,’ went on Stillington, ‘this is true. I know it full well. I myself was in attendance on the King when he gave his vows to another lady. She went into a convent it is true but she was still living at the time when the King went through a form of marriage with Elizabeth Woodville.’

‘My lord Bishop, do you realise what you are saying?’

‘Indeed I do, my lord. I have pondered long on this matter. There is only one other occasion when I mentioned it and I told the one whom I thought it most concerned: the Duke of Clarence.’

‘You told my brother this!’ Richard stared in horror at the Bishop. ‘When ... when?’

‘It was just before his death.’

It was becoming clear now. Events were falling into place. Stillington in the Tower. Clarence drowned in a butt of malmsey. Clarence would have had to die, possessed as he was of such knowledge.

How deeply it concerned Clarence, for it meant that he, not Edward’s son, was heir to the throne!

And Clarence had died. Edward had seen to that. At the same time he had imprisoned Stillington and suddenly the Bishop had found himself in the Tower.

But why had Edward let him go free? Wasn’t that typical of Edward? He always believed the best of people. He wanted to be on good terms with them. He could imagine his saying to Stillington: ‘Give me your word that you will tell no one else and you shall go free on payment of a trivial ransom.’ And Stillington would give his word to Edward, which he had kept until this moment. But he was of course exonerated from his promise now.

He was speaking slowly. ‘You say my brother married ... before he went through the form of marriage with the Queen.’

‘I say it most emphatically, my lord. For I performed it.’

‘My brother had many mistresses ...’

‘The Queen was one of them, my lord.’

‘No doubt this was some light of love ...’

‘No, no, my lord. The lady was Lady Eleanor Butler, daughter of the Earl of Shrewsbury. She was a widow when the King saw her.’

‘He had a fancy for widows or wives it seems,’ murmured Richard. ‘Go on. Old Talbot’s daughter.’

‘Her husband had been Thomas Butler, Lord Sudeley’s heir. She was some years older than the King.’

‘He liked older women,’ mused Richard.

‘He went through this form of marriage with her. She was his wife when he went through a form of marriage with Elizabeth Woodville. The Lady Eleanor went into a convent and I discovered that she died there in 1468.’

‘So she died after he went through the form of marriage with Elizabeth Woodville.’

‘Exactly, my lord. You see what this means?’

‘It means that Elizabeth Woodville was the King’s mistress and the Prince now living in the Palace of the Tower is a bastard.’

‘It means exactly that, my lord.’

‘My lord Bishop, you have shocked me deeply. I beg of you to say nothing of this to anyone ... anyone whatsoever, do you hear?’

‘I shall remain silent, my lord, until I have your permission to tell the truth.’

‘I appreciate your coming to me.’

‘I thought it was something which should be told.’

‘It must be kept secret. I must ponder on this. I must decide whether or how it should be acted upon.’

‘I understand, my lord, and I give you my word.’

‘Thank you, Bishop. You have done right to tell me.’

When the Bishop had left Richard stared in front of him visualising the prospect ahead of him.

Jane Shore was happier than she had been since the death of the King. It was a revelation to her that she was actually beginning to care about the man she had intended to dupe and who for years she had deeply resented. But Hastings was very different from that brash young man who had tried to abduct her. She had become an obsession with him over the years when he had watched her with the King and realised her qualities. Now he was finding that kindliness, that gentle wit, all her outstanding beauty was for him.

His friends laughed. Hastings has settled down, they said. His wife, Katherine Neville, daughter of the Earl of Salisbury had long been indifferent to his philanderings. They had had three sons and a daughter so the marriage could be called successful after a fashion. They did not attempt to interfere with each other’s way of life and Hastings had been closer to the King than to anyone else on earth. Edward had even said that when they died they should be buried side by side so that, good friends that they had always been in life – apart from that one occasion when the Woodvilles had sought to sow discord between them and had quickly discovered that it was useless – they should not be parted in death.

Jane talked to him a great deal about the Queen. She was rather sad about her; Hastings believed her conscience worried her. Had she wronged the Queen by taking her husband from her? Hastings laughed at that. Edward had had many mistresses and the fact that Jane had been his favourite had not harmed the Queen in any way.

The King was in the Palace of the Tower and no one whom he wished to see was prevented from seeing him – except his mother and his brother and sisters who were in Sanctuary. No one prevented them but what would have happened to them if they had emerged was uncertain.

He was delighted to see Hastings, knowing him as his father’s best friend. He did know that his mother did not like Hastings but he had a vague idea that it was due to the fact that they went out a great deal together drinking and carousing with women. It was understandable. But all the same Edward could not help being attracted by Hastings.

Hastings had a similar charm to that of the late King. He was good-looking, easy to talk to and made a young King who was not very sure of himself feel absolutely comfortable in his presence. He was very different from his Uncle Gloucester who was so serious always and made him feel at a disadvantage. Mistress Jane Shore visited him too. No one stopped her and he had always liked Jane. She was always so merry and at the same time she seemed to understand that he grew tired quickly and that when his gums bled and his teeth hurt he was a little irritable.

Jane would say: ‘Oh it’s those old gums again is it. Not really our King who scowls at me?’

She understood that he didn’t want to be miserable but he couldn’t help it; and that made him feel a great deal better.

‘I wish I could see my mother,’ he said. ‘I wish she would come here. Why does she have to hide herself away?’

‘I could go and see her in the Sanctuary and tell her you want to see her.’

‘Would you, Jane?’

‘But of course. There is nothing to stop my visiting her.’

‘I am the King. I should be the one to say who goes where.’

‘You will in time.’

‘Anyone would think my uncle Richard was the King. I wish my brother Richard would come here. We could play together and I wouldn’t be so lonely.’

‘I will go to Sanctuary and tell them what you say,’ Jane promised him.

Later she talked to Hastings about the sadness of the little King. ‘Poor child, for he is nothing more, to be there in the Tower with all that ceremony! I don’t think he enjoys his kingship very much. He would rather be with his family. I know you don’t like the Woodvilles, William, but they are devoted to each other.’

Hastings was thoughtful. He did not like the Woodvilles. They had always been his enemies and particularly so since Edward had bestowed the Captaincy of Calais upon him. If they could have done so they would have destroyed him. He had supported Gloucester because he was so strongly against the Woodvilles, and he had thought he would be Gloucester‘s right-hand man as he had been Edward’s. But Buckingham had arrived – Buckingham who had never done anything before this day. And now here he was firmly beside the Protector so that everyone else was relegated to the background.

Hastings was turning more and more against Gloucester with every day. Perhaps Jane had something to do with this. She liked the Woodvilles; she had this ridiculous notion that she owed something to the Queen because she had taken her husband. The Woodvilles were powerful even though Rivers and Richard Grey were in prison, Dorset in exile and the Queen and her family in Sanctuary.

Then it began to dawn on Hastings – with a little prompting from Jane – that as by siding with Gloucester against them he had promoted Gloucester, so perhaps he could relegate Gloucester to a secondary place by supporting the Woodvilles. His visits to the young King showed him clearly where the boy’s sympathies lay. The King wanted to be with his family; he trusted his family; he had been brought up by Woodvilles to believe in their greatness and goodness and he had learned his lessons well. Any who wanted to be friends with the King would have to be friends with the Woodvilles.

This last decided Hastings. He had finished with Gloucester who had taken Buckingham so strongly to his side so that there was room for no one else, although but for him the King would have been crowned before Gloucester even knew of his brother’s death. Very well, he would turn to the Woodvilles. He would feel his way with them and the first thing would be to let the Queen know of his change of heart.

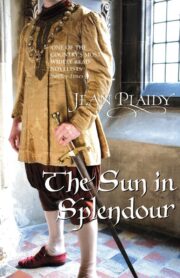

"The Sun in Splendour" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "The Sun in Splendour". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "The Sun in Splendour" друзьям в соцсетях.