And when she retired that night she said to herself: “Death is in the air.”

She was right. The following May Charles met his sister Henriette at Dover. There he secretly signed the treaty with Louis XIV, pledging himself to join France in an invasion of Holland and to confess his conversion to Rome. There was one clause which had decided Charles to sign. He could declare his conversion at a time of his choosing. That was what he clung to, for who was to say when was a good time to make such a declaration. It might well be that there would never be a good time.

But Louis would pay his pension all the same.

He was distressed that he could not spend longer with his beloved sister; but her husband the jealous Philippe, would not allow her to tarry even on the business of his brother, Louis XIV.

So Charles must content himself with this brief glimpse of his beloved sister; and even while he mourned to lose her, his eyes alighted on one of her beautiful maids of honor. Her name he learned was Louise de Kéroualle and she was a Breton; he begged his sister to leave her in England, but this Henriette told him she could not do because she was responsible to the girl’s parents.

However, Louise and Charles exchanged looks and he knew that when he sent for her she would come to him.

So Henriette left in triumph, having received the signature for which she had come, to return to the King of France whom she loved and to her husband whom she hated; and she was a little sad to be leaving the brother whom she loved, for she knew that for the sake of the King of France she had persuaded him to do a reckless thing.

Charles was gallantly gay, knowing that he would not suffer because he was determined not to. He would receive Louis’s money and keep his side of the bargain—in the words of the treaty—“when he considered the time had come to do so.”

It was not such a bad arrangement, to let the King of France finance him for the sake of a vague promise. The only risk was that what he had promised should become known to his subjects. But he doubted not that he would know how to deal with an emergency should it arise.

Henriette returned to France and almost immediately news came that she was dead. Poisoned, said the rumors, through drinking iced chicory water.

When Charles heard the news he went to his apartments and stayed there. Never had the Court seen the King so stricken, and there was an air of melancholy everywhere.

The Duchess of York murmured: “Another death in the family. Oh, yes, indeed, death is in the air.”

The Duke and the Duchess were reading letters which had been brought to them at Richmond, where they now spent the greater part of their time. The Duchess found it difficult to conceal her illness and kept to her apartments for days at a time. When the pain threatened she took sedatives containing opium and thus kept it at bay. But she knew that she was coming near to her end. For this reason her main preoccupation was with the future life. She was reading a letter from her father—a sad man in exile—for she had thought it necessary to tell him that she had become a Catholic.

He was disturbed. She knew that he believed the source of his troubles had been her union with the Duke of York, but she was convinced that this was not so. His overbearing manner, his criticism of the King’s way of life had become unsupportable to Charles; moreover it was natural that the King should want younger ministers, men such as Buckingham, more like himself.

She was a foolish woman, wrote Clarendon. She should take great care. In every way was the Church of England superior to that of Rome. He knew her obstinacy, however, and he could understand from the mood of her confession that she was convinced and would stand firm. Therefore he was giving her a word of advice. If she wanted to keep her children at her side, then she must keep also her secret. Once she confessed that she was a Catholic, the King would be forced by the will of the people to take them from her.

These words made her ponder, for she knew there was much truth in them.

In his apartments James was also receiving disturbing news. This had been carried to him by a Jesuit, Symond, who had brought it from Pope Clement IX.

James had wanted to know whether the Pope would give him a dispensation if he, a Catholic, kept his religion secret and worshipped openly in the Church of England.

The answer was No. As a true Catholic he must proclaim himself as such, no matter what worldly advantages were lost to him.

Neither the Duke nor the Duchess were enjoying reading their letters.

James had been ill and was now convalescing at Richmond and it gave him great pleasure when Mary sat in his bedchamber and read or talked to him. She wished that she could have been happier in his company; she could not understand why she did not feel—as she could only express it—comfortable. She had listened to conversations in the nursery and whenever she was with her father she remembered these; she had a vague and unpleasant idea of his activities, and inwardly she shrank from him because she could never rid herself of images which came into her mind.

Then there was her mother who seemed daily to grow more ugly. Mary promised herself that she would never eat to excess, for she believed that her mother’s bloated and unhealthy appearance was entirely due to the enormous amount of food she consumed. Anne, who had inherited her mother’s appetite, should be warned.

It was the earnest wish of the Duke and Duchess to live these weeks as a happy family, to prove to themselves that their efforts to marry had been well worthwhile. The Duke remained at Richmond, faithful to his wife; the Duchess had grown gentle and uncritical, in fact she was often too exhausted to be anything else.

But with the children—Mary, Anne, and little Edgar—she attempted at times to be gay; and sometimes they would play games together; but there was an unnatural gaiety about those games which Mary detected; and those weeks which should have been so happy were overshadowed for her by a lack of ease. A sense of doom hung over her family and because she did not understand why it was there, who had caused it to be there, and what it was, she was all the more fearful.

There was a hush throughout the Palace. Mary, Anne, and little Edgar were in the nursery with Lady Frances and the Villiers girls. Even Elizabeth was subdued.

The Duchess of York had given birth to a daughter who had been named Catherine after the Queen. The infant was weak, though still living, but the Duchess was sinking and there was little hope of recovery.

The gentle Portuguese Queen Catherine had come to her bedside and was with her now. The Duke was there too and there had been much mysterious comings and goings.

Mary with Anne and Edgar waited in silence to hear what was happening; all day long they waited and no one came to tell them.

The Duke knelt by her bedside, remembering moments from the past which now seemed to him to have contained complete happiness. Never again would she upbraid him for his infidelity; never would they talk together of the mysteries of faiths. His eyes were wet with tears. He wanted her to live, for he could not imagine life without her.

His recent illness had weakened him and he wept easily. He thought of the children in the nursery, Mary, Anne, Edgar, and the new baby who, like Edgar, already had the mark of death on her.

“James,” whispered Anne.

“My dearest?”

“Stay with me till the end.”

“I could not bear to leave you.”

“You must, James, soon, for the end is near.”

“Do not speak of it.”

“So you cared for me in very truth? Do not weep then, but rejoice. Soon I shall be past all pain.”

“You are content to go, my love?”

“The pain has been great, James, but I die in the true faith. Do not let anyone come to my bedside and attempt to dissuade me. I know the way I am going. It is the chosen way.”

“Have no fear,” said James.

“And you believe as I believe?”

“I do.”

“Then I am content.”

When a messenger had entered the room to say that Bishop Blandford was outside, James left the sickroom and went to him.

“Your Grace,” said Blandford, “I trust I am in time.”

“The Duchess cannot see you,” James replied. “She is a Roman Catholic and does not wish to be disturbed now with attempts to bring her back to the Church of England.”

“Your Grace, allow me to see her. I will not attempt to dissuade her. I will speak to her as to a Christian of either Church.”

“If you will swear to do this you may see her. I will not have her disturbed.”

The Bishop promised and went to the Duchess’s bedside.

When he had left, having kept his promise, James sent for Father Hunt and certain people whom he knew to be of the Catholic faith. The last rites were performed and when this was done the Duchess asked her husband to come near to her.

He was holding her in his arms, the tears streaming down his cheeks, when she died.

James asked that Mary be brought to him; he wanted to see his favorite child alone.

As soon as she entered the room Mary knew what had happened for he stood looking so lonely and desolate; and when he saw her he held out his arms.

“My dearest daughter, we are alone now. She has gone.”

He picked her up and rocked her in his arms as though she were a baby.

“I have my children,” he said. “Thank God she has left me them.” He began to talk about her mother, telling of her virtues and how they had loved each other with a rare devotion; he trusted that when Mary married she would make as happy a marriage as that of her parents.

As happy a marriage as that of her parents? But what of the rumors? What of Margaret Denham … and others? What of the quarrels she had overheard? Had he forgotten? Could it be that he was not truthful?

He talked of when she married. She knew in that moment that she never wished to marry. She would like to live forever with her dear sister Anne.

“I don’t want to marry, Father,” she said.

He smiled and stroked her hair.

“So you will stay with your old father and comfort him, eh?”

It was not what she had meant, but the thought seemed to please him so she said nothing.

The Duchess was buried in Henry VII chapel at Westminster, and it was noticed that the Duke of York looked more and more to his elder daughter for consolation.

THE BRIDE FROM MODENA

Soon after the death of the Duchess of York two new girls were introduced to the household at Richmond—Anne Trelawny and Sarah Jennings; and with the coming of these two the power of the Villiers was undermined, Anne Trelawny becoming Mary’s great friend and Sarah Jennings, Anne’s. Elizabeth Villiers was furious but there was nothing she could do about it; and she was beginning to realize that she had not been very clever because now that Mary was growing up she was becoming more important and the attitude of those around her was changing.

Mary herself was aware of this. “When I have my own household,” she confided to Anne Trelawny, “I shall dismiss Elizabeth Villiers.”

As yet she was far from that happy state.

Young Edgar died very soon after his mother, to be followed almost immediately by the new baby Catherine. The Duke was very sad and declared that he could only find comfort in the company of his daughters.

“Why does death always happen to us?” Mary asked him.

He held her tightly and put his cheek against hers. “It is happening all over the world,” he explained. “It is a sad fact that many are born not to reach manhood or womanhood. But we must be good to each other, my little daughter, for you and Anne are all I have to love now.”

She looked steadfastly into his face and thought of the rumors she had heard. “The Duke of York, like his brother, is a great lover of all women.” Whispers. Laughter. There were many women, according to what she had heard. Then how could she and Anne be the only ones he had to love?

“You have been hearing talk of me,” he said, and she felt the blood hot in her cheeks. Now he was going to tell her something shameful, something that she believed she would rather not hear.

“You have heard that I have been ill. It’s true I believe that I was going into a decline; but my health has improved, dearest Mary. I shall be with you for a long time yet.”

Her relief was evident. So he was referring to his ill health not that vaguely mysterious shameful life. He saw it and misconstrued the feeling which prompted it; his eyes became very tender.

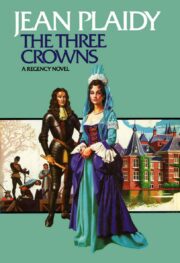

"The Three Crowns" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "The Three Crowns". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "The Three Crowns" друзьям в соцсетях.