There were three other ladies who were considered suitable: these were the Princess Mary Anne of Wirtemburg, the Princess of Newburgh, and Mary Beatrice, Princess of Modena. These three were charming girls, but the most delightful of all was Mary Beatrice who was only fourteen years old.

Peterborough first visited the Duke of Newburgh with the object of reporting to his master on his daughter. He found her charming, but a little fat—and since she was so now, he asked himself what she would be in ten or fifteen years’ time. He did not believe her worthy of his master, and as his object was known and he went away without completing arrangements for a marriage, this was never forgiven the Duke of York but remembered against him by the young lady for the rest of her life.

A picture Peterborough acquired of Mary Beatrice enchanted him for it showed him a young girl of dark and startling beauty, but since she was not yet fifteen it had been decided that negotiations should go ahead for bringing the Princess of Wirtemburg to London.

Mary Anne of Wirtemburg was living in a convent in Paris and hither Peterborough hastened, where he asked for an interview with the Princess and told her that her hand was being sought by James, Duke of York, heir presumptive to the British crown. Mary Anne, a gay young girl who found convent life irksome, was delighted, and being inexperienced unable to hide this fact. Peterborough was relieved, although he thought often of that lovely young girl who was by far the most beautiful of all the candidates.

These negotiations however were destined to fail, for suddenly Peterborough had an urgent message to stop them.

Having already informed Mary Anne that she was to marry the Duke, he was horrified by these instructions. It appeared that the King’s mistress, Louise de Kéroualle, who was now the Duchess of Portsmouth, had selected a candidate—the daughter of the Duc d’Elbœuf; and although the King guessed that his mistress’s plan was to bring her fellow-countrywoman into a position of influence that they might work together, so besotted was he that he allowed the negotiations already begun by Peterborough to be withdrawn.

It was typical of Charles that while he listened to his mistress and made promises to give her what she asked, he should find an adequate excuse for not doing so.

Mademoiselle d’Elbœuf he decided was too young for marriage to the Duke of York, being not yet thirteen; and James, being of more sober years, needed a woman who could be a wife to him without delay. So Louise de Kéroualle did not have her way as she had hoped; but at the same time it was impossible to reopen negotiations with Mary Anne of Wirtemburg.

The Duke of York must be married. There was one candidate left. It was therefore decided that plans to marry James to Mary Beatrice of Modena should go forward without delay.

When James saw the picture of Mary Beatrice he was completely captivated and felt faintly relieved—although he would not admit this—that Susanna had rejected him.

When he showed it to Charles the King agreed that there was indeed a little beauty.

“She reminds me of Hortense Mancini,” said Charles, nostalgically, “one of the most beautiful women I ever saw. You’re in luck, brother.”

James believed that he was. “Why,” he said, “she cannot be much older than my daughter Mary.”

“I can see you are all eagerness to have her in your bed.”

James sighed: “I have a desire for domestic happiness. I want to see her at my fireside. I want her and Mary and Anne to be good friends.”

Charles raised his eyebrows. “Spoken like a good bridegroom,” he said. “One thing has occurred to me. The Parliament will do all in its power to stop this marriage. Your little lady is a Catholic and they will not care for that.”

“We must make sure that the matter is settled before Parliament meets,” said James.

“I had thought of that,” Charles told him slyly.

He wanted to ask: And how is Susanna at this time? But he did not. He was kind at heart; and he was relieved that James had come out of that madness so easily.

Henry Mordaunt, Earl of Peterborough, Groom of the Stole to the Duke of York, had a task to his liking. He was going to Italy to bring home Mary Beatrice Anne Margaret Isobel, Princess of Modena, and although his previous missions of this nature had ended in failure, he was determined this should not; he was secretly delighted because as soon as he had seen the portrait of this Princess he had made up his mind that she was the ideal choice for his master.

Peterborough was devoted to the Duke of York; he was one of the few who preferred him to his brother; and since Mary of Modena was quite the loveliest girl—if her picture did not lie—that he had ever seen, he wanted to bring her to England as the new Duchess of York.

James had pointed out to him the necessity for haste. “Because,” James had declared, “unless the marriage has been performed before the next session of Parliament, depend upon it they will make an issue of the fact that she is a Catholic and forbid it to take place.”

Peterborough had therefore left England in secrecy; he was, he let it be thought, a private gentleman traveling abroad for his own business.

When he reached Lyons after several days, and rested there for a night before proceeding, he was received with the attention bestowed on wealthy English travelers, but without that special interest and extra care which a messenger from the Duke of York to the Court of Modena would have received. He planned to be off early next morning that very soon he might be in Italy.

While he was resting in his room a servant came to tell him that a messenger was below and would speak with him. Peterborough asked that the man be brought to his room, thinking that a dispatch had followed him from England. To his surprise it was an Italian who entered.

“I come, my lord,” he said, “with a letter from Modena.”

Peterborough was aghast. How did the writer of the letter know he was on his way to the Court. Who had betrayed his mission?

He took the letter and the messenger retired while he read it, but the words seemed meaningless until he had done so several times.

“The Duchess of Modena has heard of your intention to come here to negotiate a marriage for her daughter Mary Beatrice Anne Margaret Isobel, and wishes to warn you that her daughter has no inclination toward marriage, and that she has resolved to enter a convent and lead a religious life. I thought I must give you this warning, that you may convey to your Master His Majesty King Charles the Second and His Royal Highness the Duke of York, that while the house of Esté is very much aware of the honor done it, this marriage could never be.” This was signed “Nardi,” Secretary of State to the Duchess of Modena.

Peterborough was bewildered. His secret mission known! And moreover the Duchess already declining the hand of the Duke of York for her daughter!

And these messengers, what did they know of the contents of the letters? Was the project being discussed in Modena and throughout the countryside? Was this going to be yet another plan that failed?

Peterborough was determined that this should not be.

He asked that the messenger be sent to him and found that there were three of them. He offered them refreshment in his room.

While they drank together, he said: “It is strange that the Duchess of Modena should think it necessary to write to me. I am only a traveler who is curious to see Italy.”

But of course they did not believe him; and as soon as they had left him he sat down to write to Charles and James, to tell them of this incident.

All the same, he lost no time in continuing with his journey, and in due course arrived at the town of Placentia, where he found Nardi, the writer of the letter, awaiting him.

“I have come,” said Nardi, “to deliver to you a letter from the Duchess of Modena in which she herself will confirm all I wrote to you. Her object is, that such a great country as yours should not openly ask for that which cannot be granted. There are other Princesses in the family who might interest the Duke of York.”

Peterborough replied, thanking the Duchess for her concern for him, but he was a private person.

All the same he fancied that the Duchess, while telling him that Mary Beatrice was not available, was very eager for him to choose another member of her family. And why not? Alliance with Britain was a great honor done to the House of Esté, petty Dukes of a small territory. Peterborough did not believe in all this reluctance; and the more he thought about the matter, the more determined he became to bring back Mary Beatrice for his master.

The reason for the Duchess’s attitude was the young girl herself, her fourteen-year-old daughter.

The Duchess loved her daughter dearly. Her children, Mary Beatrice and Francisco, who was his sister’s junior by two years, had been left in her care when her husband Alphonso d’Esté had died. Laura Martinozzi, Duchess of Modena, was not of royal birth, although she belonged to a noble Roman family, but she had sufficient energy and wit to rule her little kingdom. She was a strong woman, determined to guard her children; and when Alphonso died—he had suffered from the gout for many years—she was determined to be both father and mother to them.

She loved them with the force of a strong nature, but this love rarely showed itself in tenderness because she was determined to prepare them to face the world and for this reason she decreed that they should be most sternly brought up.

Mary Beatrice loved her mother too, because it quickly became apparent to her that all the whippings and penances which were imposed on erring children were for their own good. If she could not repeat her Benedicite correctly she would receive a blow from her mother’s hand which sent her reeling across the room; when on fast days it was necessary to eat soupe maigre, a dish which revolted Mary Beatrice and made her feel absolutely sick, she was forced to eat it, because her mother explained, it was a religious duty. The little chimney sweeps with their black faces had frightened Mary Beatrice when she was very young for she thought they were wicked goblins come to carry her away; and the Duchess, hearing of this, forced her little daughter to go into a room where several little chimney sweeps had had orders to wait for her. There she was to talk to them, in order to learn that fears must be boldly faced. Little Francisco’s health suffered from bending too closely over his books and the doctors thought that he needed more exercise out of doors. “I would rather not have a son than have one who was a fool without learning,” was the Duchess’s answer.

She was the sternest of parents, but in spite of this had so aroused her children’s respect and admiration that they loved her. No sentiment was allowed to show; there was only sternness; but each day the Duchess spent much time with her children; she supervised their lessons and was present at meals, and they could not imagine their lives without her. She was the all-powerful, benevolent, stern but strict guardian of their lives.

When Mary Beatrice was nine years old her mother decided that she should go into a convent where she would be educated by the nuns. Here in this convent she found an aunt, some fifteen years older than herself, in whose charge she was put, and life flowered suddenly for Mary Beatrice. The affection of her aunt astonished and delighted her, because she had never been allowed to feel important to anyone before; she still admired her mother more than anyone in the world, but she loved her aunt; the nuns were kind too, kinder than her mother had been. If she made a little error there was no resounding box on the ears; and since she was not forced to eat soupe maigre, life in the convent was so delightful by comparison with that of the ducal palace that Mary Beatrice decided that she would become a nun and spend the rest of her days there.

This was the state of affairs when she was recalled from the convent to the ducal palace.

Her mother received her with more warmth than was usual and Mary Beatrice knew that she was secretly pleased.

“Sit down, my daughter,” said the Duchess. “I have news for you, which I think you will agree with me is excellent.”

“Yes, Mother.”

“The Duke of York will most certainly be the next King of England.”

The Duchess paused. “You do not seem to understand.”

“I am sorry, Madame, but I have never heard of the Duke of York nor of England.”

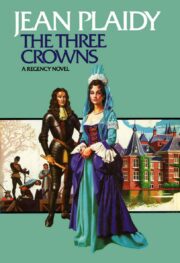

"The Three Crowns" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "The Three Crowns". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "The Three Crowns" друзьям в соцсетях.