She was the only woman who had ever resisted him. Oh, not quite, he supposed. There were always those occasions when he sent out tentative lures only to discover that there was no point in expending further energies on a siege. But he had never been rejected on any occasion when he had made a determined effort to attract and even made a definite verbal offer.

And now he had been rejected-three times-by the same female, and a servant at that, a girl past her first bloom and without a penny in the world. And there was probably the attraction, he realized as soon as he had mentally verbalized the facts. He was experiencing the universal human craving for what cannot be had.

She did not wish him ever to touch her again, she had said. What a thoroughly unnecessary admonition! His very sanity might depend on his staying as far away from her as circumstances would allow.

The Dowager Duchess of Middleburgh bestowed a benign look on her butler. The man had just informed her that her triumph was now finally complete. He had not said those words, actually. He had merely announced in his well-trained confidential tones that were designed to carry no farther than her own ears that the Earl of Rutherford was downstairs in the hall, requesting a private word with her.

"Show him up," she said.

The butler, long trained not to contradict his lady, looked her briefly in the eye to see if she could possibly have missed the detail about the private interview, understood that she had not, made a stiff obeisance, and withdrew himself from the drawing room to carry out orders.

The duchess meanwhile smiled sympathetically at Lord Beasley and Mr. Menteith, who for lack of other entertainment had been thrown into each other's company, and offered them more tea. It was extremely gratifying to know that her charge was too busy to do more than pass the time of day with two such eligible bachelors. Beasley was somewhat too fond of his victuals and the wine bottle, it was true, and consequently was bound together into one large, creaking bundle by heavy stays; it was true too that Menteith was without title, and most of his fabulous wealth had been amassed by his father through trade. But it was a splendid triumph to see them in her drawing room when dear Jessica had so far made only one public appearance.

Jessica had Sir Godfrey Hall sitting on one side of her, engaging her in spirited conversation, and Hope on the other. Miss Menteith was sitting shyly on a stool at her feet, gazing up at the three conversationalists with an almost worshipful attitude. There were some who would have frowned at the girl's visiting with her brother when she would not be brought out until the following spring. But what could one expect of the off-spring of a gentleman unconventional enough to go into trade and galling enough to repair the family fortunes thereby?

"The Earl of Rutherford, your grace," the butler announced in tones that clearly but silently added, "and don't blame me for the consequences neither."

"Ah, Charles," the dowager said, advancing on him with one hand extended, her expression all gracious innocence. "I have been expecting you, m'boy."

It said something for the boy's experience with life, she thought approvingly, that he stopped abruptly on the threshold of the room for only a moment before recovering himself and advancing into the room to make his bows to all its occupants. He was unable to summon a smile, but then modern manners were not what they had been in her day.

She forced him to accept a cup of tea and limp his way through a stilted conversation with Beasley and Menteith for all of five minutes before taking pity on him finally and laying a hand on his arm.

"Charles and I have some private business to discuss for a few minutes," she said graciously to the room at large. "Do, pray, excuse us."

"Certainly, Grandmama," Lady Hope said, while several of the others gave low assenting murmurs. "Do come back before leaving, though, Charles. I rely on you to escort me home as I dismissed my maid when I arrived. And Mama will certainly be happy to see you. You have called at the house only twice since returning from the country, you know."

Lord Rutherford bowed in the direction of his sister, carefully avoiding the eyes of Jessica, the dowager noticed with certain amusement, and followed his grandmother from the room and into a small study.

"Grandmama!" he said, clearly rattled. "You did not misunderstand my message, I take it?"

"That you wished to see me privately?" she asked. "I assumed you did not realize there were visitors and would not wish to appear rude, m'boy."

"You know very well why I asked to see you alone," he said. "It will not do, Grandmama. She has no business in this house. Certainly not as a guest. And certainly not socializing with the likes of Hope and Beasley and Menteith. Your joke is quite distasteful."

"Sit down, m'boy," she said, motioning to a brocaded chair on one side of the desk while she took one on the other side. "You are far too tall to argue with. Puts me at a disadvantage. I assume you refer to Jessica?"

"You know I refer to her, Grandmama," he said. "She is a governess, a servant. And one not even in good standing at present. To my knowledge she has no money, no prospects. Without your mad intervention she would now be walking the streets. And I begin to think that that is where she belongs."

"Oh, I think not," the dowager said with maddening calm. "I do not for a moment believe that you think that, Charles. You think that she belongs in your bed. Can't say I altogether blame you. A pretty and quite delightful little thing."

"If it is in my bed she belongs," Rutherford said, "it is as my whore, Grandmama, paid for the services she renders there and forever kept apart from the sort of company with whom she now mingles in the drawing room. She is there now, for goodness' sake. With Hope. My sister."

"If Hope has not already been contaminated by contact with you," the duchess said soothingly, "I doubt she will be by Jessica, Charles. After all, you have been whoring for ten years and more."

He got abruptly to his feet. "That is an entirely different matter," he said. "I am a gentleman."

"Utter poppycock!" his grandmother said coolly. "Sit down, Charles, and lower your voice, m'boy. Nothing is ever gained by losing one's temper. I thought the gel did very nicely last night, didn't you? She would have been a great success even without your gracious assistance."

"It was a damned trick, Grandmama!" he said, putting his clenched fists down on the desk and leaning across it toward her. He had not obeyed the order to sit down. "You deliberately lured me there last night to witness what dupes the two of you could make of Lord Chalmers and all his guests. All right, you succeeded. But the matter must be left there. Find the woman employment. Let her go. This way, someone is going to get hurt. Probably even her. You are giving her ideas beyond her station."

"Calm yourself, Charles," the dowager said, leaning back in her chair and spreading her hands, palm up. "Actually, we have no quarrel with each other. I happen to agree that Jessica belongs in your bed. But not as your fancy piece. Far too vulgar. As your wife, m'boy. As your countess."

7

Lord Rutherford rested his fists on the desk and stared for a moment into his grandmother's eyes. Then he gave vent to an incredulous bark of laughter.

"You want me to marry Jess Moore?" he said. "The woman who was governess to your last choice of bride for me?"

"I imagine her education and talents were very much wasted in the post," the dowager said. "I think she would make you an eminently suitable bride, Charles. The gel has beauty and breeding. She has character. More important, she has spirit. She will be able to keep you in line after your marrige. And you really must settle down, m'boy. Middleburgh-your grandpapa-had his sidelines, you know, but he was ever discreet. I grant him that. And you are the future Middleburgh, though I wish long life to your father. Won't do for you to settle a mousy wife in the country breeding while you continue to sow your oats in town."

"I agree with you on essential points, Grandmama," Rutherford said. "But how can you possibly suggest that woman as my future duchess? My wife must at least be of the same social class as I."

"Jessica is a lady," his grandmother pointed out.

"Oh, yes," he agreed, "she is somewhat above the rank of scullery maid, I grant you. Her father was a country parson, Grandmama. She admitted as much to me last night. She even added that he was impoverished and unable to afford to send her to school."

"Gels also have mothers," the dowager said.

He made an impatient gesture. "Her mother was probably one of the royal princesses, of course," he said. "I will not do it, Grandmama. I will not even consider the matter. And I will not see the woman again. You may stop trying to throw us into company together. You will be wasting your efforts."

"Your mama will disapprove of your not spending Christmas with the family," the dowager said innocently.

"At Hendon Park?" he asked with a frown. "Of course I shall be going there. I always do."

"Then you will be seeing Jessica again," she said.

A dull flush colored Rutherford's cheeks. "You are never taking her there," he said. "To our private family Christmas, Grandmama?"

"She is my guest for the winter," the dowager said. "Where else would she go, Charles? And how would I look back with clear conscience on the memories of my dear friend, her grandmama, if I left her here?"

"Which fictitious character doubtless has a name, a home, a history, and a genealogy reaching back at least five centuries," her grandson said.

"Don't sneer, Charles," she said. "It spoils your looks. You are quite right, of course." She paused, looking sharply at him, waiting for the question that did not come. She nodded briskly. "Now, dear boy." She rose to her feet and reached for his arm. "We will return to the drawing room where Hope will be waiting for you. And you will have the chance to be civil to Jessica. She was otherwise occupied when you arrived."

"I shall make my bow," he said. "Beyond that I will not go."

"Just a word of advice for the future," his grandmother said, patting his arm. "Jessica is my guest, Charles, and is to be treated with the proper decorum. You must not offer her carte blanche again, m'boy.

Twice is quite enough. She will begin to find you tedious if you risk a third."

"She told you about last night, then," Rutherford said with some contempt, reaching out and opening the study door. "I might have known that she would go running bearing tales."

"Not by any means," she said. "But I am not quite in my dotage, boy. When a gel disappears with my grandson for almost half an hour and returns with an angry glint in her eye and a mouth that looks quite thoroughly kissed, I do not conclude that they have been discussing Latin literature."

"She refused me again," he said. "She sees that she can gain more from clinging to you, it seems."

"And quite right too," she said. "You should try to eliminate that spiteful inflection from your voice when speaking of such disappointments, Charles. You are a man of close to thirty years, not a spoiled schoolboy, m'dear."

"Sir Godfrey was unable to spend Christmas with us at Hendon Park last year," Lady Hope was telling Jessica. "His father was ill, and he felt obliged to go to his sick bed. But he is to come this year. We often invite close friends, you know, even though it is mainly a family Christmas. I believe you have made an impression on Sir Godfrey, my dear Miss Moore. As you have with several other young men. And that is as it should be. You are very lovely. If I were ten years younger, I should be positively jealous of you."

"You are very kind," Jessica said. "Everyone has been kind. I did not expect to have visitors today after only one appearance in public."

"Oh, there is nothing at all strange about that," her companion said, reaching out and patting Jessica's hand. "Even I, my dear, had my fair share of admirers during my first Season. The fact that Papa is a duke probably had something to do with that, of course. I was never a beauty."

Jessica smiled, but she was not given the chance to frame a reply.

"Oh, you do not need to pity me," the older woman said with a little laugh. "I knew at a very young age that I would never be pretty. Faith was, you see, and when people used to call her pretty and then turn to me and say I was handsome-always with a little pause before the word, my dear-I knew what they meant. I have never allowed the fact to disturb my sleep. I once loved, you know."

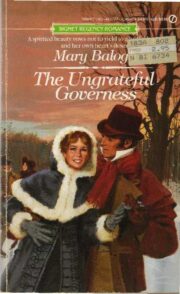

"The Ungrateful Governness" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "The Ungrateful Governness". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "The Ungrateful Governness" друзьям в соцсетях.