He knew what he would want to do with Jess, or to her, at Hendon Park, Rutherford thought with a flash of the anger that had consumed him for all of the previous evening. And it had nothing to do with marriage or with acting the courteous host, either. Marry her! Make her the Countess of Rutherford, the future Duchess of Middleburgh. Fill her with his children!

Rutherford's jaw tightened. He wanted her. God, he wanted her.

She was looking into his eyes suddenly, appearing rather as if she were thoroughly trapped, as if she had caught herself by surprise. Her eyes widened, drawing him into their dark blue depths.

"Do you not think so, my lord?" she asked somewhat lamely.

"I beg your pardon," he said abruptly. "I confess I must have been daydreaming. I do not know to what you refer."

Sir Godfrey laughed. "Miss Moore agrees with me that I should consider making the usual Grand Tour now that the Continent is safe for travel again," he said. "Italy in particular should not be missed."

"To my certain knowledge, Godfrey," Rutherford said dryly, "you have been considering just such a journey since long before Boney was safely shut away on St. Helena. All you need is for someone to assure you that such an undertaking would not be self-indulgent. It sounds as if you have all the champions you need in Hope and Miss Moore."

"I have always felt it a dreadful injustice that ladies are not encouraged to the same extent as gentlemen to travel," said Lady Hope. "I for one would like nothing better than to see Rome and Florence. Oh, and Naples. We ladies seem to travel beyond our own shores only when we have husbands to take us. Is that not right, Miss Moore?"

"It is because most ladies are such delicate creatures and would suffer from the hardships of the journey," Rutherford said. "You hear only about the beauty of the Sistine Chapel in Rome and the pleasure of the gondolas in Venice and the wonder of the leaning tower in Pisa, Hope, and nothing about the discomfort of the lodgings in France and the vile smell of the canals in Italy and the endless vermin everywhere."

"I think that is a myth put about by gentlemen in order to persuade us to resign ourselves to our lot," Jessica said. "I am sure that Lady Hope and I could endure the odors and the itching with as much philosophy as you, my lord, if we only had the works of Michelangelo to gaze upon while we scratched."

Her eyes, looking directly into his own, danced with merriment for one unguarded moment, Rutherford noticed, startled. Then those eyes wavered and dropped to the capes of his greatcoat again, and her face sobered.

"A hit!" declared Lady Hope, clapping her hands. "You have silenced Charles, Miss Moore. He can think of no argument to refute your logic, you see. Unfortunately, that does not mean that you and I may now go and pack our trunks." She laughed.

"Ah, here we are!" Sir Godfrey declared cheerfully as the carriage lurched and slowed down. "Michelangelo may not be available to you. Miss Moore, but the clowns of Astley's will be a worthy substitute, I'll wager. Lady Hope, may I help you to alight, ma'am? It would be a shame for me to bear off Miss Moore and leave you to a mere brother's care, would it not?"

Rutherford's eyes met Jessica's across the width of the carriage. Both sat still until Lady Hope had been helped down the steps. Then Rutherford vaulted out onto the pavement and held out a hand for Jessica's.

"I do beg your pardon," he said quietly as she stepped down in front of him. "I was given a firm command not to touch you again, was I not? It seems that circumstances have made it difficult for me to comply."

She looked up into his eyes, her gloved hand still firmly clasped within his. "Do we have to do this?" she asked in an undertone. "Can we not at least be civil since it seems that we are to be in company together more than either of us would wish?"

He raised one eyebrow. "Yes, you have done very well in placing yourself quite firmly in the midst of my family, have you not?" he said. "You are to be congratulated, Jess. But have no fear for my manners, my dear. I am, I believe, always civil to ladies and to others of the same gender."

She turned sharply away from him before he could be quite sure if it was tears that suddenly brightened her eyes. He grimaced and held out his arm for her support. How could he have said what he had when the very words refuted his meaning? He felt ashamed of himself and irritated with her for causing him to feel so.

"Please take my arm," he said. "The crowds can sometimes be rough here, I have heard. Astley's attracts spectators of widely varied social status."

"I should be right at home here, then," she said coldly, grasping her pelisse and walking off in pursuit of Sir Godfrey and Lady Hope.

Lord Rutherford was left standing, his arm extended, feeling foolish. He was forced to hurry after her and protect her as best he could with a hand at the small of her back, a gesture that merely made her straighten her spine and walk on.

Damnation take the woman, Rutherford thought. One of these times-just once!-he was going to get the upper hand in an encounter with Jessica Moore.

8

The Earl of Rutherford did two things that evening that he had not done in years, and one other that he had not done in weeks. He gambled at Boodle's, a club he did not often frequent, though he had been a member for years, and won upward of three hundred pounds. He got drunk at the same club, almost but not quite to the point of incapacity. He even had an embarrassing memory the next morning, which he hoped was merely part of his night's fuddled thoughts, of delivering some sort of monologue and attempting a song. Embarrassing indeed for someone who had disappointed a mama and two doting older sisters by failing to produce one note of music by way of his vocal cords throughout his childhood and boyhood.

And he spent the murky hours between something after midnight and the twilight before dawn in bed with a woman he had no business going to bed with. He had looked in on an old crony on the way home from Boodle's, purely on drunken whim. His way had taken him past the house, and the lights were still blazing in the windows. He walked in on a party that looked as if it should have died a natural death an hour or more before. And he walked off less than half an hour later with Mrs. Prosser on his arm. Rather, he drove off in her carriage, and it was probably he who had been on her arm, he thought later, when he was trying to retrace all his activities of the night.

He could have had Mrs. Prosser years ago. He could name a dozen men who had. She was a widow and had the means and the inclination to remain so. She was willing to tell anyone who was interested enough to listen that she became easily bored with just one man. She had endured Mr. Prosser's unimaginative attentions for three years until the elderly man had had the good grace to bow out of this life and leave her free to indulge her fancies.

Rutherford had always avoided coming to the point with her. She was received by all except the very highest sticklers. He preferred to choose his bedfellows from among those women whom he would not afterward be forced to meet socially. Besides, Mrs. Prosser was an aggressive, voluptuous woman, and Rutherford liked to be totally in charge of what happened between the sheets of any bed he happened to occupy.

However, he thought just before dawn, as he stumbled home, trying to shake the fuzziness from his head and knowing that it was impossible to do-hangovers could not be shaken off at will-one could not expect to act rationally when one was drunk. Mrs. Prosser had taken him home and into her bed, and he supposed that he must have been satisfied with what happened there, because it seemed to him that it had happened more than once, perhaps even more than twice.

His valet hurried into his room, looking only slightly tousled, a few minutes after he had arrived in it. Rutherford was glad. He was sitting on the edge of the bed telling himself to remove his coat and his cravat and yet seemingly unable to lift his hands from their resting place on the bed either side of him.

"Warm water, Jeremy," he said, his nose wrinkling with distaste at the smell of some feminine perfume that clung to him. "Please," he added as an afterthought to the servant's retreating back.

The long-suffering Jeremy tucked his master into bed a short while later, fussed unnecessarily with the heavy velvet curtains that were already tightly drawn across the lightening windows, and tiptoed with theatrical caution from the room.

Rutherford groaned. He remembered now very clearly indeed why he had resolved five or six years ago never to get drunk again. The certain knowledge that he would feel wretched for all of the coming day did nothing to comfort him.

Dammit, he thought, lowering the arm he had flung over his eyes to his nose, he could still smell that woman's perfume. Mrs. Prosser, of all people. She was not at all the sort of woman he found appealing. She had seduced him pure and simple. She had taken advantage of his drunken state. Yet another reason for never getting drunk again! And where was the point of spending half a night making love with a woman when one could not afterward recall whether one had done so once, twice, or three times, or even-horror of horrors -no times at all?

But no, at least he could not be guilty of that humiliation. He could clearly recall her twining her arms around his neck as he was leaving, kissing him lingeringly on the lips, and declaring that she had not spent a more energetic and enjoyable night since she did not know when. Which said nothing about the caliber of his performance, of course, since the woman had meant to flatter, but it was at least an indication that there had been a performance.

Damn the woman! Rutherford thought, heaving himself over onto his side and wincing from the pains that crashed through his head. Damn her to hell and back. She was a nobody, an impudent, opportunistic, conscienceless nobody. And yet she had driven him into conflict with his grandmother; she had forced him into uncharacteristically unmannerly behavior; and she had pushed him into gambling, drinking, and whoring, none of which activities he had undertaken from choice.

Damn Jessica Moore!

He did not believe he was a naturally conceited man.

He had never thought of himself as arrogant. He had a sense of his place in society, yes, but then that was the way of life. Everyone around him had a similar sense, he had always believed. He had always treated servants with courtesy. He had always been charitable to those in need of charity. He had always been courteous and more than generous to his women.

Why, then, did Jess Moore make him feel like an arrogant snob? No, she did not make him feel like one. She made him become one. Of course he was outraged at her effrontery in trying to pass herself off as a member of the beau monde. Anyone of any sense and decency would agree with him. It was she who was in the wrong. Entirely so. There was no question about it. His attitude was perfectly correct. There was nothing cruel, nothing merely snobbish in his disapproval.

Why was it, then, that she made him feel so brutal? Why was it that a few cold words from her could put him instantly in the wrong? His feeling of guilt the afternoon before at Astley's had ruined the first few performances for him. He had been unpardonably rude to her and could not excuse himself even with the assurance that the provocation had been great. By retaliating with words that were so uncharacteristic of him he was merely lowering himself to her level.

Sitting next to her at the circus, Hope at her other side, Godfrey beyond her, he had wanted to take Jess's hand in his again and beg her to forgive him. She sat so rigidly upright next to him that he knew he had made her miserable. She deserved to be miserable, of course, he had told himself. And he had convinced himself; he had not apologized. Thank God, he had not apologized. But he had still felt guilty.

And very aware of her. It would have done him a great deal of good if he had had to endure rejection now and then through his adult years, he supposed. It surely could be only her rejection of him that made him want her so badly. He could not recall ever having had this all-pervading, aching need for one particular woman.

Why should it be so? Really, when it came right down to the physical act of bedding, one female body was very much like another. Why the craving for the one woman who chose not to bed with him?

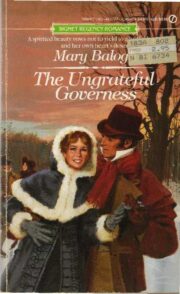

"The Ungrateful Governness" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "The Ungrateful Governness". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "The Ungrateful Governness" друзьям в соцсетях.