"Jeremy." Lord Rutherford slapped down the third ruined starched neckcloth onto the dressing table before him. "My damned fingers are all thumbs today. Come and work one of your miracles."

The valet, busy brushing invisible lint from the green superfine coat that he was all ready to help his master into, crossed the room in some surprise. It was only on the most gala of occasions that he was ever called upon to perform his art's supreme creation: a well-tied neckcloth.

"Hif your lordship would 'old your 'ead still for one minute," he scolded a few moments later, "hit would be done and over with."

"Sorry," his lordship muttered meekly, holding his head poker still. He was nervous. By God, he was nervous! He would not be surprised to find that if he held out his hands, they would be shaking. Lord Rutherford smoothed his hands over his waistcoat and turned to reach his arms into the sleeves of the coat Jeremy was holding out for him. He would not put the matter to the test.

Well, it would all be over within the next hour or so, he consoled himself. And it was after all something he had never done before. And if it was something that every man intended to do only once in his life, he supposed he had some right to be nervous. Even if she was an ex-governess, a social nobody.

It was his own idea, he was convinced of that. He had not been browbeaten into it by his grandmother. She had been quite annoying the night before, it was true, but his mind had been made up even before she appeared on the scene. Or almost, anyway.

She had not followed his mother and Jess to the supper room. She had seated herself in the music room, occupying the chair on which Jess had sat, while he crossed to the abandoned violin and picked it up to inspect it. He had hoped that she would go away. A fond hope where Grandmama was concerned!

"And when might I expect you to call to pay your addresses, Charles?" she had asked archly.

He had run his thumb experimentally across the strings of the violin. Why pretend to misunderstand her? Her meaning was pretty obvious.

"Tell me more about her, Grandmama," he had said without looking up. "Who is she?"

"My dear boy," the dowager had said, "you must know far more about Jessica than I do. Every time you are in company with her you seem to get very close to her indeed. You were not offering her carte blanche again just now, were you? Very poor form, m'boy. Only marriage will do under the present circumstances. She is my guest, you know, and has been received by your sister."

"And is the granddaughter of the dearest friend of your youth," Rutherford had said, lifting the violin to his chin and drawing the bow across its strings. "Is that true, by the way? I find it hard to penetrate the tissue of lies that both you and Jess seem bent on throwing my way."

"Of course it is true," she said carelessly. "But of course you will not believe me. You owe her marriage, Charles. You have been with her unchaperoned for a quite scandalous length of time this evening, and both your mama and I have witnessed your holding her hand and kissing her. On the lips, no less."

"Tomorrow," he had said, laying the violin down at last and looking at his grandmother for the first time. "If you will engage to be at home tomorrow afternoon, Grandmama, I shall call to make my offer."

"Oh, splendid, Charles!" she had cried, getting to her feet and clasping her fan to her bosom. "I really did not think it would be quite this easy, m'boy, I must confess. But you will not be sorry. Jessica is the ideal wife for you, princess's daughter or barmaid's daughter notwithstanding. She will be at home tomorrow. You have my word on it."

But it was not she who had trapped him into doing it. Perhaps he would not have gone quite as soon as today, but sooner or later he would have been preparing himself for this same errand. He had known as he sat beside Jess in the music room that his words to her were quite true. He was obsessed by her. They were fated to end up together. It had been equally obvious to him that the time when she might perhaps have been persuaded to become his mistress was well past. Jessica Moore might not have a legitimate claim to move among the haute ton, but she was there now and seemed to have been accepted with remarkably little inquiry.

No, he had decided as he took her hand in his and ached to gather her completely to himself, if he wanted Jess-and he did want her, had to have her, in fact- then he must marry her. The thought should have shocked him, repulsed him. Even the thought of her resident in his grandmother's house had offended his notions of proper behavior just a few days before. But the idea came with ease and little resistance from his rational mind.

She was, after all, accepted by society. It seemed that she was not completely beyond the pale of his social milieu. It seemed likely that her father had been able to lay claim to membership of at least the lower gentry. She was educated and accomplished. Her total absence of dowry would matter not at all to him. He already had more money than one man should fairly expect in a lifetime. And she was refined. And beautiful. And very desirable. Achingly so. He did not believe he could go on living with any degree of comfort until he could somehow make her his own.

And the more he thought about it, the more he realized that it would not be enough after all to establish her in some quiet dwelling where he could visit her and enjoy her at his leisure. There would be something missing from his pleasure. He wanted Jess in his own home. He wanted to be able to take her about with him, show her off to the people of his world, take her home with him at night, or return there to her and make love to her to his heart's content without that tedious necessity of rising at dawn to return to the respectability of his own establishment.

Yes, he had decided he would marry Jess. And he had little understanding of why he should be nervous about going to make his offer to her. She wanted him too. She had admitted as much both in words and in action. And it would be a very advantageous marriage for her even if she did not. Yet he was nervous. Jess was the one woman he had ever found to be unpredictable. Their encounters never progressed quite the way he expected. He had the quite unreasonable fear that she might reject him.

Jeremy helped his master into his heavy greatcoat and handed him his beaver hat and cane. Lord Rutherford hesitated for only a moment before striding out of his room and down the branched marble staircase that led to the tiled hall below. One thing he must not do was betray any of his nervousness or uncertainty. Jess Moore had already wounded his masculine pride on several occasions. He must at least show confidence in claiming her as his bride.

"It is a great pity you are too unwell to join me in a walk, my dear Miss Moore," Lady Hope said. "It is such a beautiful day. Cold, but crisp, you know. However, I suppose Grandmama knows best, even if you do protest that you feel perfectly healthy."

"Jessica is unused to an active social life," the dowager said from the fireside chair in her own drawing room. "Often one can be exhausted without realizing the fact, and it is just at such times that exercise like walks and drives can bring on a chill. We would not want anyone to be poorly over Christmas, now would we?"

"Certainly not, Grandmama," Lady Hope said. "My dear Miss Moore." She patted the hands of the young lady sitting next to her. "How annoyed I was to see that Charles had taken you away to the music room last evening. Sometimes my brother has no more sense than a small child. And just at a time when Sir Godfrey so clearly wished to converse with you. And I thought myself so clever to take Lord Graves out of the way. I mean to have a talk with Charles."

"But I really did wish to hear the musicians," Jessica said. "It was unfortunate that we heard only part of one of their performances. Miss Lacey played before supper."

"However," Lady Hope said cheerfully, "Mama was sensible enough to bring you to join our table for supper. And did you notice how deftly I brought the conversation around to the Elgin marbles, Miss Moore? Sir Godfrey was clearly grateful for the opportunity to offer to take you to see them."

Jessica smiled. "He had talked of them earlier in the evening," she said. "Though he did warn me that it is not considered quite the thing for ladies to go."

"Pooh," Lady Hope said. "We are not such poor-spirited creatures, are we? Why, Grandmama has been to see them and professed herself quite impressed."

"Gentlemen like to see us as poor wilting females, who do not even realize the fact that they possess more flesh than what we see on their hands and faces," the dowager said. "If you wish to impress when you make this visit, Hope and Jessica, you must appear suitably shocked to discover that indeed there is considerably more."

"I shall be sure to engage Lord Graves in constant conversation," Lady Hope said. "You will enjoy having Sir Godfrey explain everthing to you, Miss Moore. He is very clearly taken with you, you know."

Jessica laughed. "And yet it was to you he first issued the invitation, Lady Hope," she pointed out.

"But of course, dear." Her companion patted her hand again. "He had to make sure that you would be properly chaperoned before he could invite you. And we are old friends, you know. He would feel that he must invite me."

Jessica smiled and said no more. Gentlemen could be left in an unenviable predicament, she felt, if they must always ask a chaperone first. What if the real object of their invitation then said no?

"Ah," the dowager said as the door opened to admit her butler. "Who is having the audacity to call on me this afternoon? Everyone knows this is not my day for visitors."

"The Earl of Rutherford, ma'am," that austere individual said, bowing woodenly before standing aside to admit the guest.

"Ah, Charles, m'boy," the dowager said, offering her cheek as he strode across the room. "What a surprise. To what do we owe this pleasure?"

"Hope. Miss Moore." Lord Rutherford did not feel one whit the less nervous now that he was there. And he would have felt far more comfortable if his grandmother had not chosen to put on this great pretence. "I trust you are both well?"

"Oh, perfectly, Charles," his sister said. "I must tell you that Faith was most gratified that you came to her soiree last night and stayed the whole evening. I do believe Lady Sarah was not displeased either."

"Lady Sarah?" Rutherford frowned his incomprehension as he seated himself.

"You were in conversation with her for all of an hour, I dare wager, after supper," his sister said archly. "I do believe she has been angling for you since last Season, Charles."

"Lady Sarah!" he said with a frown. "The chit was in her first Season last year, for God's sake, Hope. She is a mere babe. She talked to me for the whole hour last evening about her lapdogs, I do believe. At least, that is what she was talking about every time I brought my attention back to her."

"Charles!" Lady Hope admonished him. "I am quite sure you cannot be as indifferent to the charms of all ladies as you pretend to be. It would be most unfair when all the young ladies are far from indifferent to you."

"Cut line, Hope, will you?" Rutherford said. "Or I shall start making insinuations about you and Graves. You seemed to be together for much of last evening."

"Don't be absurd, Charles," she said. "What would Lord Graves see in an aging spinster like me? I was merely trying to keep him out of Sir Godfrey's way, you see, so that he would be free to speak with Miss Moore. But you had to come along and assume that she wished to listen to the music."

"My apologies!" Rutherford said, his eyes straying for the first time to Jessica, who sat with her eyes downcast. She was pleating the wool of her dress between her fingers.

"Hope, my love." The dowager duchess rose to her feet, a determined look on her face. "Every year I face the same problems as Christmas approaches. Which of my clothes should I have my maid pack away to take with me? And what gifts will be suitable for each member of the family? It must be advancing age. I never used to give a thought to either matter. Come to my sitting room and help me."

"Me, Grandmama?" Lady Hope viewed her grandmother in some amazement. "You know you will never take advice from anyone."

"Age, my dear," the dowager insisted. "I begin to think I will have to change my habits. My brain is not as firm as it used to be."

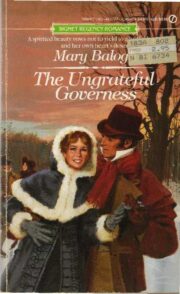

"The Ungrateful Governness" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "The Ungrateful Governness". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "The Ungrateful Governness" друзьям в соцсетях.