A moment later she was ushering Lady Hope out of the drawing room. "We will not be long, dear," she said to Jessica. "Entertain Charles for me until we return, will you?"

Jessica stared at the closed door in some dismay. Then she turned suspicious eyes on the man sitting quietly across the room from her.

"Why have we been left alone?" she asked. "That was quite deliberate, was it not? Is there something going on that I do not know of?"

"It seems so," he said. He was sitting perfectly relaxed. He was even half smiling at her. "I wondered if Grandmama would prepare you. It seems that she has not."

"Prepare me?" Jessica was on her feet. She felt instant alarm.

"I am here to make you an offer," Lord Rutherford said.

"An offer?" Jessica stared at him, her hands clenched at her sides.

He held up a hand as she drew breath to speak again. "Of marriage, of course," he said. "Did you think it was carte blanche again, Jess? I would not repeat that suggestion again, my dear. And you must know that Grandmama would not conspire with me in such a case. It must be marriage between you and me." He got to his feet to face her. He smiled full at her. "Will you do me the honor?"

Jessica was staring at him incredulously. "Marry you?" she said. "You wish me to marry you? How positively absurd! Of course I will not marry you."

He raised his eyebrows and strolled toward her. "Is your answer a considered one?" he asked. "Did I not express myself well enough, Jess? Was it an arrogant proposal? Do you wish me to go down on my knees? I will, you know. And I am very serious."

"Why?" she asked. He could see that her knuckles were white, her hands balled into fists at her sides. "Why do you wish to marry me, my lord?"

"I told you last night that I am obsessed with you, Jess," he said. "We are meant for each other. I do not believe I can do without you any longer."

Jessica laughed, though there was no amusement on her face. "It must be a poweful obsession indeed, my lord," she said, "if you are willing to marry me in order to get me into your bed."

"But you feel it too, Jess." He reached out a hand and took one of hers. He held it palm up, uncurling the suddenly nerveless fingers with his other hand. "We want each other. I believe we need each other. We must marry. There is no other choice."

"Despite the fact that my mother was a scullery maid?" she asked. Her head was thrown back, her expression scornful.

He smiled, trying to keep the uncertainty out of his expression. "I do not believe that story," he said. "But yes, even despite that fact, Jess."

"Then finally we have one thing in common," Jessica said. "We are each willing to ignore the social credentials of the other. I reject your offer, my lord, despite the fact that your father is a duke."

"Why, Jess?" He was holding her hand firmly sandwiched between his own.

"I will not be anyone's whore," she said. She was staring straight into his eyes so that he could not look away. "Even with the respectability of a wedding ring. I am a person, Lord Rutherford, a whole person. I am not just a body to be used for a gentleman's bedtime pleasure. Thank you, but no."

He searched her eyes, her hand still clasped between his. Then he stood back abruptly, dropping her hand, and bowed stiffly.

"I shall wish you good day, then, ma'am," he said. "Please accept my apologies for taking your time."

And he was gone.

10

They were to leave for Hendon Park in just a few days' time. Jessica was not sure whether to be glad or sorry. She was glad that perhaps at last her future would be settled once and for all. Sorry because she was almost sure to see the Earl of Rutherford again. At least, he seemed not to have sent word to anyone that he did not intend to join his family for Christmas.

Jessica had allowed the dowager to send a letter to her grandfather. She should have written to him herself, of course. If she wanted his help-and she did-then it was only right that she be the one to write to him. Besides, it was time to patch up their quarrel. He was her only living relative, and she his. They had been fond of each other all through her childhood and girlhood. It was absurd to break all connection with each other over a stupid matter of pride. And he was not getting any younger. Perhaps the opportunity to mend their differences would not be open to her for much longer. And how would she ever forgive herself if she let the chance forever pass her by?

More than anything she needed his help. The Dowager Duchess of Middleburgh continued to shower new clothes and gifts on her and continued to extend her full hospitality. To a young lady who had been brought up to be proudly independent, it was an increasing embarrassment to accept such charity from a lady on whom she had no claim of kinship. She must let her grandfather support her, either with an allowance in her present abode or in his own home in the country.

She should have written herself. But how could she begin to explain herself to him? How strike the right note of humility without sounding servile? She had given in to cowardice when her hostess, with her usual iron-willed insistence, declared that the letter would be much better coming from her. Jessica did not know what had been in that letter except that the marquess had been invited to Hendon Park for Christmas.

There had been no reply yet. Would he come? She did not know. Her grandfather had never been given much to traveling. For this particular occasion perhaps he might. Perhaps he still loved her enough. But surely some reply would come there even if he did not arrive in person. Somehow by Christmas she would be independent again, or at least independent of all except her own family. It was something to look forward to.

And now more than ever it was imperative that she be free of her obligation to the dowager duchess. The last few weeks had been dreadfully hard to live through. It was true that she had not set eyes on the Earl of Rutherford since he had left her abruptly after his insulting offer of marriage-and neither had anyone else, it seemed. At least she had been spared that embarrassment. But she had had to face the severe disappointment of his grandmother-the same woman who was paying for her very keep.

She had returned to the drawing room with Lady Hope quite soon after Lord Rutherford's departure, but she had kept her surprise at finding Jessica the room's only occupant well concealed until her granddaughter had taken her leave. It had not taken her long after that to discover the truth.

She had been very kind. Jessica had to admit that. There was no accusation of ingratitude, no suggestion that she was no longer welcome at Berkeley Square. Quite the contrary, in fact. When Jessica, in great distress, had insisted that she must leave, whether her hostess was willing to find her a situation or not, that lady had shown uncharacteristic gentleness, patting her on the shoulder and telling her that she was a goose if she thought their friendship must come to an end merely because Jessica had had the good sense to reject "that puppy."

But she clearly was disappointed, Jessica knew. Although she rarely spoke with open kindness either to or about him, it was very clear that the dowager doted on her grandson and wished dearly that he would settle down with a wife and family. And she had wanted that wife to be Jessica. She had not pried. She had merely assumed that Rutherford had presented himself as if he were God's answer to a maiden's prayer and had offended Jessica's pride.

"Spoiled," she had said, handing Jessica her own lace handkerchief with which to dry her eyes. "Charles has always been surrounded with women ready to jump at his every bidding. Too many females in the family and not enough males. Middleburgh is no earthly good- always buried in his library or ensconced at one of his clubs. Dear Charles has grown up with the belief that he has merely to snap his fingers and a female will come running. He is too handsome for his own good too, of course. This will do him good, Jessica, m'dear. Just what he needs."

But Jessica knew that she did not mean it. She was beginning to know her hostess rather well, and the severe outer appearance hid deep feelings. Jessica knew every time a visitor was announced that the dowager looked up expecting it to be Lord Rutherford. She knew when the old lady looked around her at any gathering that she was looking for his tall, distinctive figure. And she sensed that her hostess's enthusiasm for the various gentlemen who came to call on her and take her walking and driving was somewhat forced.

Strange as the idea seemed, Jessica became more and more convinced that the Dowager Duchess of Middleburgh had grown to love her and had wished to gift her with what was most precious in her life: her grandson, the Earl of Rutherford.

Jessica did not know where he had gone and did not care, provided only that he stayed there. She did not wish to see him ever again. And she did not like to explore the reason for her reluctance. It was embarrassment merely, she would have assured herself. How can one face and be civil to a man whose marriage proposal one had rejected out of hand? It was intense dislike. The man had had only one use for her ever since he had set eyes on her. At least his offers to make her his mistress were an honest acknowledgement of that fact.

His offer of marriage was pure insult. He was desperate enough to possess her that he would even marry her to get what he wanted. Clearly he valued marriage very little. It meant nothing to him but the acquisition of an elusive bedfellow. What would he do when he grew tired of her? Presumably by that time she would have presented him with a male heir and she could be respectably housed on one of his country estates. There would be nothing to hold him after his passion cooled, of course. Unless he discovered something of her background. He would probably be suitably impressed to discover that Papa had been the youngest son of a baronet and Mama the daughter of a marquess.

Jessica was not necessarily in search of a love match. She knew that if she was to marry within her social class, she would probably marry and be married for any of several reasons. Her grandfather would wish her to ally herself to wealth and rank. She would wish also to like and respect her prospective husband. He would offer for her probably because of her relationship to the Marquess of Heddingly. She would hope also that she would be respected for her modest education and accomplishments.

She would not be married solely because she had a desirable body. And she would not marry a man for whom she felt only physical attraction. No matter how powerful that attraction was. She would never marry the Earl of Rutherford.

Her relief at not seeing him probably stemmed as much from this undesirable attraction as from embarrassment or dislike. When he was there, when she saw him, she was aware of nothing and of no one else. He was tall and athletic and of course impossibly handsome, as his grandmother had pointed out. And there was even a certain integrity in his character that drew her against her will. She knew that no matter what the circumstances, her person would somehow be safe with Lord Rutherford. There was the memory of the night at the inn, when he had entertained her with charming conversation during dinner and afterward insisted that she take his bed.

And always there were the memories of his kisses, of his touch, and the certain knowledge that he would be a lover who could make her forget all her scruples and even her very self if she would let him. And when she was with him, when he touched her, she always came perilously close to giving herself up to his care. To relax into his desire, to give herself to him body and soul, to forget that the person that was Jessica Moore mattered not at all to him, to forget that the future would hold nothing for them except a waning of passion and a long boredom: it was very hard to hold firm against all these urges when she saw him.

She was glad that he had made his offer the way he had. He had been so relaxed, so smilingly confident that she would swoon at his feet with gratitude for the great honor he had done her, so arrogant. Oh, yes, he had quite correctly labeled his own attitude. It had been relatively easy to refuse him. Anger had carried her through. And pride.

But oh, it had been difficult when he took her hand and uncurled her fingers not to lean forward to rest her forehead against his chest. And difficult not to call to him in panic when he strode from the room. Or to run after him down the stairs.

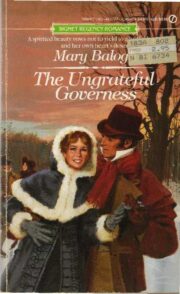

"The Ungrateful Governness" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "The Ungrateful Governness". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "The Ungrateful Governness" друзьям в соцсетях.