She had looked at him then. Through him, rather. He had had the impression that she did not see him at all.

"Thank you, my lord," she had said before turning and smiling with warm affection at the old man again, laying her cheek against his shoulder for a moment.

No questions of how it had come about that he had gone to her grandfather. No queries about his health, about his whereabouts for the past three weeks. No polite wishes that his morning's journey had been a pleasant one. No sign of any gladness to see him. Or of displeasure in seeing him. No reaction at all.;

"Charles." Hope was tapping his arm. "Claude has asked you twice already if you wish to play a game of billiards. You look as if you might be a million miles away."

The cousin in question laughed. "There must be a female in it," he said. "And where have you been for the last three weeks anyway, Charles? Is she to appear in London during the coming Season?"

The group around him all joined in the laughter.

"My lips are sealed," he said, grinning. "You don't think I would confide in you, Claude, do you, you puppy? An older cousin has to have some secrets. And I thought you had learned long ago not to humiliate yourself by challenging me to a game of billiards. It seems I have to refresh your memory. Are you coming, Godfrey?" He got to his feet.

"I shall stay to keep your sister company," Sir Godfrey replied. "I know that I would be drawn into challenging you too. And I know just as surely that you would crush me as you always do. You run along, and I shall stay here and hold on to my self-esteem."

Lord Rutherford put his arm across the shoulders of a tall, thin young lad who had been hovering in the vicinity of his group for several minutes.

"Are you coming too, Julius?" he asked. "Have you really grown a foot since last year, or is it just my imagination? Can I interest you in a game of billiards?"

Young Julius was beaming with pride as he left the room with his idol's hand still resting casually on his shoulder.

"I understand that the pond is to be scraped off tomorrow for the children to skate on," Sir Godfrey said. "And you are to accompany them, Lady Hope?"

"Oh," she said, flashing him an apologetic smile, "skating at Christmas time has always been traditional, Sir Godfrey, when there is ice. We are not always so fortunate, of course. We all go, you know. The distinctions between children and adults become somewhat blurred at this time of year."

"And is a mere family friend permitted to join the fun?" he asked.

"You, sir?" she asked. "But of course, if you wish to do so. You must not feel obliged to, of course. We will all understand perfectly if you choose to behave in a more dignified manner than the rest of us."

"How could I resist?" he said. "I do not believe I could even count the years since I last wore a pair of skates."

"You will not be the only person outside the family to be there," Lady Hope said, smiling slyly at her companion. "Dear Miss Moore is also to come."

"Is she, indeed?" he said, looking at her with a twinkle in his eye. "Then I shall certainly have to attend, shall I not, Lady Hope?"

"Is it not delightful to see her so happy?" she said, gazing fondly across the room at Jessica. "And she kept so quiet about the Marquess of Heddingly's being her grandfather."

"I suppose it would be a happy occasion to be reunited with the sole remaining member of one's family after longer than two years," Sir Godfrey agreed.

"And so pretty she looks with her fair hair and delicate complexion," Lady Hope continued.

"Indeed, yes," he said, "though sometimes I believe I prefer a dark beauty. Dark hair can be more striking."

"Perhaps," she agreed absently. "Would you not say that happiness has made Miss Moore look years younger, sir? Tonight she could pass for a girl in her first Season, I declare."

"My feelings exactly, ma'am," he said, a tremor of something very like amusement in his voice. "I suppose I must be feeling the effects of my age. I do believe my attention is usually caught these days by ladies of more mature years."

"Yes," she said, "and that is just as well. Miss Moore is four and twenty, after all. Have you told her about your horses, sir?"

"My horses?" He raised his eyebrows.

"Is she aware that you own one of the best stables of racing horses in the country?" she asked. "I am sure Miss Moore would be vastly impressed."

"I do not believe the chance to mention them has arisen in my conversations with her," he admitted. "No matter. There is always time. But what about you, ma'am? I begin to think you are not as interested in them as you have always appeared to be. You have been promising these five years past to visit my stables with your brother, but I have yet to see you there."

"Oh, me," she said with a self-deprecating laugh. "I am sure you do not wish to be encumbered with the likes of me at your stables when you must be forever busy with the horses."

"I have grooms and stable hands and jockeys to tend my horses for me," he said with a smile. "Really, Lady Hope, I am just a lazy owner who happens to have a shrewd eye for a good horse and a large enough purse to indulge my whims. I would not have invited you, you know, if I did not wish you to come."

"That is very civil of you, I am sure, sir," she said. "Perhaps when the weather improves I can accompany Miss Moore on a visit."

"A good idea," he said. "She seems to be a suitable chaperone."

Lady Hope appeared to miss this last comment. A whole flock of little children had descended on her demanding good night kisses. A nurse stood in the doorway, a firm look on her face. Evidently even the persuasions of the Duke of Middleburgh himself would not have shaken her decision that it was high time all those in her care were tucked up in their beds.

Jessica was brushing her hair absently before her mirror. She had dismissed her maid for the night several minutes before. What a very eventful day it had been!

She still could scarcely believe that her grandfather had actually come-all the way to London in the middle of winter, merely to see her, the granddaughter who had defied him and rejected his care two years before. And he had not scolded all day. He had been content to let her hang on his arm, and had even patted her hand frequently with what she could only interpret as affection.

She had not realized until this day how starved she was for love. Not that she could complain. The Dowager Duchess of Middleburgh had shown her quite remarkable kindness since her arrival in London, and for no real reason at all except that she had been a friend of Grandmama's. But Jessica had not been able to quite relax. She had been so very aware of the fact that she was living entirely on the charity of a near stranger.

Now she had Grandpapa, and everything was going to work out well for her. They had not had any sort of personal talk during the day. They had not been alone together at all. She did not know what he would suggest, whether he would stay with her in London perhaps until the Season and continue with his plans of a few years before, or whether he would take her back home with him after Christmas. At the moment she did not care. It was enough to relax her stubborn independence for just a little while and let someone else decide her future for her.

Jessica turned from the mirror and climbed into the high bed. She pulled the covers around her although she did not lie down. The fire was still burning in the grate. But it was going to be a cold night. She must warm up the bed before the fire burned itself out.

The Earl of Rutherford had brought Grandpapa. He had been gone for three weeks, and he had returned with her grandfather. Why? What had he been doing all that time? It seemed very clear to Jessica that after all he must have gone in search of her identity. And he had discovered the truth. But why? She had refused him. Why would he still show any interest in her? Had he been hoping to find some dreadfully low or even scandalous background so that he could return to

London and expose her to the ton? Yet he had said that he wished to marry her even if her mother had been a scullery maid.

It had been a happy day. She could not deny that. The happiest she had known since before Papa had died. But, oh, it had been a wretchedly unhappy day too. How was she to spend a week longer in this house when Lord Rutherford would be there too? He was there now, sleeping in his own bedchamber. She did not know where that was. Perhaps not far off.

Jessica rested her forehead on her raised knees. Did he know, couid he possibly have guessed, how achingly aware of him she had been all day, from the moment of her entry into the blue salon that morning? Could he have any inkling at all of the fact that when she had wept in Grandpapa's arms, she had done so as much because he had come back as because Grandpapa had come? She had not realized that even herself at the time. She had tried to tell herself that she was dismayed he had returned. She had tried to pretend that he was not there.

But she had known when she was forced to look at him at last. The dowager had told her that it was Lord Rutherford who had brought her grandfather, and she had been forced to look at him and acknowledge the fact. He had been standing there before the fire exactly as he had when she had entered, the same stony expression on his face. There was no sign of gladness for her happiness, no sign that he had done what he had done for her sake. He had barely acknowledged her thanks.

She had wanted to jump up at the dowager's words, throw her arms around him, and share her joy with him. But he had looked like a man made of stone. And all day he had ignored her. He had talked with almost everyone else in the house, had appeared progressively more cheerful as the day wore on, had talked with and teased the children, whose favorite he clearly was as much as Lady Hope was. But she might have been a hundred miles away.

How perverse of her to have expected or even wanted some sign from him, she thought. What did she expect? That he still wanted her? She had convinced herself and told him in no uncertain terms that she had no interest in being wanted merely. Did she expect that he would treat her with more respect, deeper regard, knowing who she really was? She would despise such a change in his behavior.

So what did she want?

Jessica turned her head to rest her cheek on her knees. She wanted his love. How very, very foolish! What had she ever done to earn the love of the Earl of Rutherford? And what had he ever done to make her crave his love? He was a man for whom the satisfaction of physical appetites was the most important thing in life. A man to despise.

Or was he? He had respected her wishes on more than one occasion, although she knew that on one of those occasions she had asked more of his self-control than any woman had a right to ask of a man. He had charm and knew how to set one at ease in conversation. There was some kindness in him. How many gentlemen would give up their bed to a mere governess? Especially when that governess did have a bed of sorts to go to? And he was dearly loved by a family of which Jessica was growing increasingly fond. There must be good in him when she had seen how anxious all his family had been lest he not appear for Christmas.

It was stupid to pretend. Of course she felt a strong physical attraction to Lord Rutherford. She would be almost unnatural not to do so. He was extraordinarily handsome, and she had moreover tasted his kisses and caresses. Yes, of course she wished to be in his bed again but without any of the moral scruples this time to prevent her from knowing the deepest caress of all. Of course she wanted all that. Her body ached and throbbed at that very moment for his touch.

But it was not just that. Oh, of course it was not just that. She wanted Lord Rutherford. All of him. Every-thing that made him the person he was. She wanted him to talk and talk to her, as he had at dinner at the inn. She wanted to share her thoughts and emotions with him as she had done unconsciously at Astley's. She wanted to laugh and be teased by him, as his nephews and nieces and cousins had been that day. She wanted to know him.

Could one love someone one did not really know very well at all? If not, what other name could she use to describe this feeling that was washing over her, that would not let her go? This feeling she had not been free of since that night at the inn?

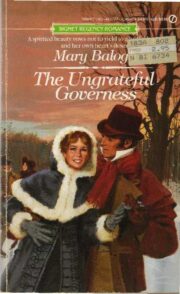

"The Ungrateful Governness" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "The Ungrateful Governness". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "The Ungrateful Governness" друзьям в соцсетях.