"He gave me his card," Jessica admitted, "and told me I might send to him at any time."

"It's not his style to set up a mistress," the duchess said. "But if he offered, he will keep his promise. You could do worse, child."

"I tore up his card before I reached London," Jessica said.

"But you still think you will not have to walk the streets," the duchess mused.

"Yes, ma'am."

"You have somewhere else to go, then, even though you clearly do not wish to go there."

"Yes, ma'am."

"Well," the duchess said briskly, seeming to have come to some decision, "I shall certainly have to do something for you, my dear, or Charles will never let me forget it. You have the look of your grandmother, you know, to quite a remarkable degree."

"Oh, do I?" Jessica said, looking up pleased that the duchess had committed herself to helping her. "Thank you so much, ma'am."

The dowager duchess sat quietly looking at the eager face across from her until it lost its glow and blanched. The eyes in the pale face grew huge.

"You know? You knew my grandmother?" she whispered.

"It is a rough fate for you, is it not, my dear," the duchess said soothingly, "to have been directed to the house of a woman who my grandson claims knows everyone in the kingdom?"

"But I have my father's name," Jessica said. "You cannot possibly have known him."

"No," the duchess admitted, "but it so happens that your grandmother the marchioness was my particular friend. We made our comeout together, you know-a long time ago, my dear. And indeed, the resemblance between you is almost uncanny. I remember well how very upset she was when her only child-they were not as fortunate as we were, you see; their only child was a gel-insisted on marrying a country parson. I even recall the name Moore, my dear. I have a memory full of such apparently unimportant details. Adam was his given name?"

Jessica nodded, feeling numb.

"And I recall how very miserable poor Mirabel was when your mother died in childbed and your father would not allow the marquess to help at all in your upbringing. Yes, I even remember the name Jessica. Your papa allowed you to visit your grandparents only once a year and for only one week?"

Jessica nodded again.

"And then poor Mirabel died herself," the duchess said, "and I heard no more news of you or your father. You did not feel you could turn to your grandfather for help when your father died?"

Jessica shook her head.

"And you don't wish to tell me the reason why," the old lady said after waiting for a moment. "So be it. So now, what do we do with you, grandchild of my dear friend?"

"Please help me find employment," Jessica said. She felt as if she were viewing the duchess and indeed the salon and herself through a long tunnel. She had not intended that anyone but she should ever know more of her identity than her father's name.

"I hardly think it appropriate for the only granddaughter of the Marquess of Heddingly to take employment as a governess," the duchess said, frowning.

"But it is what I wish," Jessica said, leaning forward and staring anxiously across at the older lady. "There is no alternative, your grace. At least, no alternative that I wish to take."

"Oh, I think there is," the duchess said. "I think it would be quite appropriate for me to entertain the granddaughter of one of the dear friends of my youth. Up from the country to spend the winter with a lonely old woman. Come to meet society. Not quite as exciting as it would be in the spring during the Season, of course, but not bad even so. There are quite sufficient people here during the winter for you to cut quite a dash."

Jessica was on her feet. "Oh, no, ma'am,'" she said. "No. I could not possibly. Please. I did not come here to beg such favors."

"Of course you did not," the dowager duchess said haughtily. "No one has held a dueling pistol against my breast to force me to offer my hospitality. I do so quite freely. But you will find that once I have my heart set on anything, it is almost impossible to cross my will. Save yourself a losing fight, my dear, and sit down again. Tell me where I must send for your trunks. You will move in here today, and I shall have a dressmaker and a hairdresser brought to the house this afternoon. We have to rid you of that dreadful gray and that quite horrid hair style. I suspect it will not be difficult to make a beauty of you. And I would say so even if I were not sure from the fact that Charles tried twice to seduce you."

Jessica blushed and sat down.

The Earl of Rutherford called on his grandmother again during the afternoon of the following day. It was the afternoon of the week when she was known to be at home to callers. His return visit would therefore be less conspicuous, he thought. And realized immediately that if he believed that he was fooling no one but himself. She had known even two days before that his visit was unusually soon after his return from the country. She would know as soon as she saw him today that his interest in Jessica Moore was greater than he had tried to make it appear.

And it irritated him to know that it was so. Why should he care what happened to the woman? He was not really responsible for her. And he had given her the chance of a secure future. Two chances. She would have lived far more comfortably as his mistress than she had ever lived in her life, he would wager. And when she had refused that life, he had sent her to his grandmother. And Grandmama would not let him down. She would find something for Miss Moore.

Why should he be worried, then, worried to the point of scarcely sleeping the night before and of rushing to Berkeley Square for the second time in three days? Why should he be worried that she would not have gone to his grandmother? He fervently hoped that she had. He had an uncomfortable feeling that he was going to be roaming the streets of London, searching all the favorite haunts of prostitutes for the next several weeks if she had not.

Damn that woman! Rutherford thought as he handed his greatcoat, hat, and gloves to a footman and followed the butler upstairs to his grandmother's drawing room. She had stood before him in the parlor of the Blue Peacock Inn the morning after his sleepless night, the little gray governess all over again, her eyes not once directed at anything but the floor, coolly refusing all his most charming and lordly invitations to ride with him in his carriage. It had been almost impossible to imagine, looking at her, that she was the same woman who had lain hot and aroused in his arms for all too brief and unsatisfactory a period the night before.

Damn her! He hoped she had come and that Grandmama had sent her to a remote corner of Wales or Scotland. Then he could put her out of his mind and seek out more grateful female companionship that night.

"Ah, Charles, m'boy," the duchess said when he was announced, "I have been expecting you. I am in the middle of telling these ladies that I am soon to have company. Young granddaughter of one of the dearest friends of my youth. Coming for the winter. I am going to introduce her to society."

"You, Grandmama?" Rutherford stared at her in some surprise, his eyebrows raised.

"Lonely in my old age," she said vaguely. "I shall enjoy it."

It was only later, when the arrival of more visitors led to less generalized conversation that she was able to add for the ears of her grandson only, "Young chit, Charles. Might make a good wife for you, m'boy. I shall expect you to show her some attention."

Rutherford pulled a face. "So far, Grandmama," he said, "I don't thoroughly approve your idea of eligible females. I am sure that with your connections you will be able to marry her off in a fortnight. Especially if her father has money. Did Miss Moore come yesterday?"

"Eh?" she said vaguely. "Oh, your gray governess, Charless. Yes, yes. I have dealt satisfactorily with that matter."

"You have found her a situation?" he asked.

"Yes, yes," she said with a dismissive wave of the hand. "Now about this gel, Charles. She will be new to society, you know. I shall be counting on you to bring her into fashion."

He grimaced. "I suppose that means dancing with her at assemblies, sitting in your box at the opera, and such like," he said. "Well, Grandmama, I suppose one favor deserves another. I shall play the gallant. But only for a few days, mind. If she is from the country, the girl is bound to be a dreadful bore."

"We shall see," the duchess said, rising to her feet and advancing on a pair of new arrivals, one hand extended graciously.

5

Jessica looked at herself full-length in the mirror once more. She had dismissed the maid fifteen minutes before. But she still deemed it too early to go downstairs.

What she saw in the glass did not entirely displease her, she had to admit. After two years in unrelieved gray, with her hair constantly pulled back into an unbecoming bun, she felt a certain delight to see herself in a colored gown. The apricot silk fell loosely from beneath her breasts. It was adorned with heavy flounces around the hem. The plain scooped neckline was daringly low, she felt, though both the dowager duchess and the dressmaker had assured her that it was quite conservative. The short puffed sleeves were trimmed with miniature flounces to match the hem. She wore apricot slippers and long white gloves.

And her hair! It had rarely been cut in her life, and then only because she had felt the ends were lifeless and split. Papa had held that a woman was intended to leave her hair long, and she had always respected his opinions. She still could not believe the lightness of her head without all the bulk. Her hair was still not short as the hairdresser had tried to persuade her was all the crack. It was twisted up into a topknot. But the severity was all gone. Soft curls framed her face and trailed along her neck. She really looked quite pretty, she thought privately, for all her four-and-twenty years.

And what an advanced age it was to be making her first appearance in society. And at a ball at that. She had never thought to attend a real grand ball. Indeed, she had been taking dancing lessons for the past five days, brushing up on the steps of the country dances they had performed on the village green at home, learning the more elegant dances, including the scandalous waltz, against which her father had spoken so strongly when he had heard of it.

And what was she doing, Jessica thought, turning away from the mirror again and toying with the brushes on the dressing table, in residence at Berkeley Square with the Dowager Duchess of Middleburgh, friend of her grandmother? And what was she doing allowing the duchess to clothe her and train her in the social skills and organize a social life for her? It was the very life she had refused to allow her own grandfather to provide for her two years before. She had chosen rather to make her own way in life. She had become Sybil Barrie's governess.

She had loved her grandparents while her grandmother lived. During the one week of each year that she spent with them, she had loved to explore the house with its many treasures and to roam the estate, both on foot and on horseback. And this despite the fact that her grandfather had never had anything good to say about her father. Her grandmother had been a gentle soul who was content to pour out the love of her lonely heart on her one grandchild, whom she saw so seldom.

After Grandmama's death, the visits had been less enjoyable. Grandpapa had been forever criticizing her drab appearance, her love of reading, her serious ideas on life, religion, and politics. He had wanted her to come and live with him so that he could make her into the lady she should be by birth. He had wished to send her to school. She had quarreled quite violently with him two years before her own father's death when he had accused Papa of dreadful things including stealing and then killing her mother. She had refused to visit him after that.

She might have gone to him after her father's death. Although she was of age, she had led a quiet and sheltered life. She was frightened by the prospect of being alone. Her father had left almost nothing beyond a pile of books. But the marquess had come to her and had angered her beyond bearing when he told her his plans for her. They included a Season in London and a dazzling marriage, both of which she had secretly dreamed of for years. But his manner had been irritating. He had not consulted her wishes at all. And he had loudly criticized her poor dead father yet again for holding her back from her birthright until she was already fairly on the shelf.

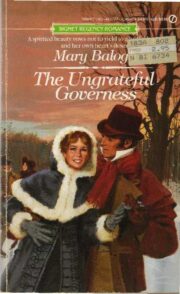

"The Ungrateful Governness" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "The Ungrateful Governness". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "The Ungrateful Governness" друзьям в соцсетях.