“What about the poison?” Eleanor went on. “How was it administered? In the tea?” She waved her own teacup fearlessly.

“Traces of prussic acid were found on the broken pieces of teacup the bishop held. None in Louisa’s.” That had been a great relief. Even if she’d drunk from her cup, Louisa would have been safe.

On the other hand, the fact that she’d by chance chosen the innocent cup woke Fellows up at night cold with fear. What was to say the poison hadn’t been meant for Louisa in truth? Perhaps Hargate had poisoned the cup himself then drunk the wrong one by accident. Or had there been no target—only a madman waiting to see which guest dropped dead?

Either way, Louisa had survived a close call. Fellows, who hadn’t prayed since he’d been a boy and forced to church on occasion, had sent up true thanks to God for that.

“No poison in the teapot, then?” Eleanor asked.

“None. In the bishop’s teacup only.” Fellows took a sip of coffee, which was rich and full, the best in the world. Of course it was. “Lady Louisa, since you are here, I’d like you to tell me—think carefully—why you picked up that particular cup to hand to the bishop.”

Louisa lifted her shoulders in a faint shrug. “It was the easiest to reach.” Her voice was tight, as though she hadn’t used it for some time and hoped she wouldn’t have to. “A clean one, placed on a tray. I had to reach all the way across the table for one for me. I poured Hargate’s first, to be polite.”

“So, if Hargate had gone into the tea tent alone, or someone else had, and wanted tea, they’d have reached first for that cup?”

“Yes. It would have been natural.” Louisa paled a little. “How horrible.”

“Deliberately killing another person so cold-bloodedly and letting an innocent receive the blame, that is horrible, yes.” And too close to home. Fellows wanted the man—or woman—who’d done this. He’d explain to them, slowly and thoroughly, how they’d enraged him, and what that would mean for them.

He turned to Eleanor, who’d listened to all this with interest in her blue eyes. “I’ve come to ask you, Eleanor, to tell me about Hargate. I want to know who were his friends, his enemies, and why someone would want to poison him.”

“So you are taking the assumption that he was indeed the target?” Eleanor asked.

“In a murder like this, even if it seems arbitrary, malice is usually directed at one person in particular,” Fellows said. “If the killer wanted to cause chaos and much harm, he’d have poisoned the entire pot, or all the cups. Not just one, for one person alone.”

Louisa shivered. “Gruesome.”

“The world is a gruesome place,” Fellows said to her. He wanted to shove aside his coffee, go to Louisa, sit next to her, put his arms around her, and hold her until her shaking stopped. “It never will be safe, as much as we tell ourselves we can control danger or even hide from it.”

Louisa looked back at him, her green eyes holding an equal mixture of fear and anger. He liked seeing the anger, which meant she hadn’t yet been broken by this ordeal. But there would be much more to come. Fellows longed to comfort her, to shield her from the horrors, to kiss her hair and tell her he’d make everything all right for her. But at the moment, he was trapped into being the good policeman, with no business wanting to touch her, hold her, kiss her.

He made himself drag his gaze from Louisa and continue. “Now, Eleanor, tell me about Hargate.”

Eleanor’s eyes widened. “What information can I give you? Louisa knew him much better than I did. She’ll have to answer.”

Louisa shot her a look that would have burned a lesser woman. Eleanor sipped tea and paid no attention.

“I didn’t know him all that well,” Louisa said, when it was clear Eleanor would say nothing more. “He was ambitious and became a bishop rather young, and he had family connections that helped him. But everyone knows this.”

“He was charming too,” Eleanor said. “At least, some people thought so. I never found him to be, but I’m told he had a persuasive way about him. He charmed his way into every living he held, apparently. The only person who ever blocked him was Louisa’s father, Earl Scranton, and he and Hargate had words over it.”

So had every single person Fellows interviewed told him; they’d told him as well that Earl Scranton had later taken much of Hargate’s money in fraudulent schemes.

“Why did your father cause problems for him over the living?” Fellows asked Louisa.

Louisa shrugged, looking past him and out the window. “Father didn’t approve of young men getting above themselves. The living at Scranton is quite prosperous, and Hargate wanted it. He was the Honorable Frederick Lane then. My father didn’t like him and didn’t want him to be the local vicar. He found Hargate foppish, and said he preferred an older clergyman.”

“Simple as that?” Fellows asked.

“As simple as that.” Louisa looked at him again, her eyes green like polished jade. “Hargate was angry, of course, but once he began his rise to power, he forgave my father. Well, he said, rather deprecatingly, that taking my father’s church would have held him back, so it was all for the best.”

“Forgave him enough to let your father invest money for him?” Fellows asked.

Louisa’s smile was thin and forced. “Investing with my father became the fashionable thing to do. Everyone wanted to say they’d of course entrusted their money to Earl Scranton.”

All the worse when the scheme came tumbling down. “And Hargate was angry when everything fell apart?”

Eleanor broke in. “Of course he was. So many were, unfortunately. But when I spoke to Hargate earlier this Season, he seemed unconcerned about it. No grudges there. But Hargate’s family have always given him piles of money, even though he was the second son, and he never had to worry much about the ready. Seems to me Hargate led a charmed life. He would have found a seat in the House of Lords soon and lived happily ever after. Well, happy except for being a bit bullied by Hart. But then his luck ran out, poor man.”

“And I need to find out who killed him, and quickly. That’s why I’ve come to you for help,” Fellows said, looking at Eleanor.

Eleanor contrived to look surprised again. “I don’t know what I can do.”

She did know, but she was making Fellows spell it out. “You know everyone. When I talk to them, they see a policeman prying into their affairs. No, don’t bother telling me I’m one of the family and they should treat me as though I’m a true Mackenzie. I’m the illegitimate son and always will be. When you talk to them, they see their friend Lady Eleanor Ramsay. They’ll tell you things they’d never dream of telling me.”

“And then I report it all to you.” Eleanor gave him a severe look. “You are asking me to spy on my friends.”

“I am, yes.”

Eleanor’s severe look vanished, and she beamed a smile. “Sounds delightful. When do I begin?”

“As soon as you can.”

“Hmm, Isabella’s supper ball would be a good place to start. Absolutely everyone will be there. She’s hired assembly rooms for it, because her house is far too small for such a grand event—even this house isn’t large enough to hold the entire upper echelon of English society. Besides, Hart has become quite tedious about having any large affairs here now that there’s a baby in the house, although I—”

Eleanor broke off when a small cry—more of a grunt—invaded the silence, even over Old Ben’s snores. Fellows saw now what he’d missed by focusing all his attention on Louisa—a bassinet hidden behind the sofa, its interior shielded from the sunshine by a light cloth.

Eleanor rose immediately, went to the bassinet, and lifted out a small body in a long nightgown. “Here’s my little man,” she cooed, her voice filling with vast fondness. “Forgive my abruptness, dear friends, but I wanted to pick up my son before he started howling. He can shatter the windows, can little Alec.”

Fellows had risen automatically as soon as Eleanor left her seat. Eleanor lifted the boy high, gazing at him in pure rapture. “Did you have a good nap, Alec? Look, Uncle Lloyd has come to see you.” Eleanor turned the baby and held him out to Fellows.

Fellows looked at a sleep-flushed face, tousled red-gold hair, and the eyes of Hart Mackenzie. At the age of four months, Alec—Lord Hart Alec Mackenzie, Eleanor and Hart’s firstborn—already had the hazel-golden Mackenzie eyes and the look of arrogant command of every Mackenzie male.

As Fellows stood still, unwilling to reach for this little bundle he might drop, Alec’s face scrunched into a fierce scowl. Then he opened his mouth, and roared.

Fellows had heard plenty of children cry in hunger, in fear, or in want of simple attention. Alec’s bellowing possessed the strength of his Highland ancestors, calling out for blood.

Old Ben woke up with a snort, looking around in concern. Eleanor laughed, turned Alec, and cuddled him close. “There, now, Alec. The inspector can’t help looking at you like that. He scrutinizes everyone so.” Alec’s cries quieted as he snuggled into his mother’s shoulder. Ben huffed again then laid his large head back down.

“If you’ll excuse me,” Eleanor said. “I must return this lad to the nursery for his afternoon feeding. Tell Louisa what you wish me to do, and thank you for keeping us up on the matter.”

So saying, she gathered Alec tighter and breezed out of the room before Fellows could say a word.

The closing door left him alone with Louisa. She looked up from her place on the sofa to where Fellows stood, awkwardly holding his coffee cup.

“You may leave if you wish,” Louisa said. She wanted him to, that was plain.

Fellows remained standing but set down the coffee. “I’m glad to report I was able to make the investigation turn its focus from you,” he said, trying to sound brisk and businesslike. “You’re not to be arrested unless there’s evidence solid enough to bring you before the magistrate. The coroner and my chief super don’t want to risk putting an earl’s daughter in jail unless the chance of making the charges stick is very high. I’ve convinced my sergeant and my guv that the story of the man escaping from under the tent wall is true.”

“It’s very good of you.”

Such a stiff and formal response from the woman he wanted to gaze at him in soft delight. His heart burned. “No, it’s very bad of me to lie to my own men, but I am trying to keep you out of Newgate.”

“And I am grateful to you, make no mistake.”

“But angry you have to be grateful to me,” Fellows said, his words brittle.

“No, not angry. It’s just . . .” Louisa heaved a sigh, pushed herself to her feet, and paced the sunny room. Ben watched her without raising his head. “I’m confused. I don’t know what to do, or how to think or feel. How I should think or feel. Or how to behave.”

“It’s a bad business,” Fellows said tightly.

“And now you’re trying to help me, and I’m being horribly rude. I . . .” Louisa swung around, her peach and cream skirts swishing. “Nothing in my life has prepared me for this. Even Papa defrauding all his friends was not as difficult to understand—you’d be appalled how many wealthy gentlemen are bad at simple business matters. But watching a man die and then being accused of killing him—that I have no idea how to parry.”

“Being accused?” Fellows asked sharply. “Has someone said that to you?”

“No, but they are all thinking it. I can feel them thinking it. Out there.” She waved her hand at the windows. “Even you think it.”

“I don’t. That’s why I’m trying to find the culprit.”

“If you didn’t have a doubt, you wouldn’t go to such pains to keep me from being arrested.”

Fellows stepped in front of her, forcing her to stop. “Let me make this clear to you, Louisa. You’re right that everything at this moment points to you. But if you believe our system of justice will prove your innocence, only because you’re innocent, you are wrong. If a judge gets it into his head that you’re a giddy young woman who goes around poisoning potential suitors, nothing will change his mind, not the best barrister, not the jury. Most of the judges at the Old Bailey are about a hundred years old and regard young women as either temptresses or fools. Would you like to face one of them? Or a gallery of eager people off the streets, coming to mock you? Journalists writing about what you look like standing in the dock? Every expression, every gesture you make?”

Louisa’s face lost color. “No, of course not.”

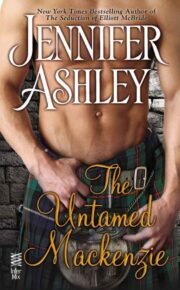

"The Untamed Mackenzie" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "The Untamed Mackenzie". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "The Untamed Mackenzie" друзьям в соцсетях.