Daniel raked in his money and winked at the dealer. She really was lovely. “You can write me a vowel for the rest,” he said to Mortimer.

Mortimer wet his lips. “Now, Mackenzie . . .”

He couldn’t cover. What idiot wagered the last of his cash when he didn’t have a winning hand? Mortimer should have taken his loss several rounds ago and walked away.

But no, Mortimer had convinced himself he was expert at the bluffing part of the game, and would fleece the naive young Scotsman who’d walked in here tonight in a kilt.

A hard-faced man standing near the door sent Mortimer a grim look. Daniel guessed that said ruffian had given Mortimer cash for this night’s play, or was working for someone who had. The man wasn’t pleased Mortimer had just lost it all.

Daniel rose from the table. “Never mind,” he said. “Keep what you owe me as a token of appreciation for a night of good play.”

Mortimer scowled. “I pay my debts, Mackenzie.”

Daniel glanced at the bone-breaker across the room and lowered his voice. “You’ll pay more than that if ye don’t beat a hasty retreat, I’m thinking. How much do ye owe him?”

Mortimer’s eyes went cold. “None of your business.”

“I don’t wish to see a man have his face removed because I was lucky at cards. What do ye owe him? I’ll give ye that back. Ye can owe me.”

“Be beholden to a Mackenzie?” Mortimer’s outrage rang from him.

Well, Daniel had tried. He stuffed his winnings into his pockets and took his greatcoat from the lady dealer. She helped him into it, running her hand suggestively across Daniel’s shoulders as she straightened his collar.

Daniel winked at her again. He folded one of the banknotes he’d just won into a thin sliver, and slipped it down the top of her bodice.

“Aye, well.” Daniel took his hat from the slender-fingered lady, who gave him an even warmer smile. “Hope you can find tuppence for the ferryman at your funeral, Mortimer. Good night.”

He turned to leave and found Mortimer’s friends surrounding him.

“Changed my mind,” Mortimer said, smiling thinly. “The chaps reminded me I had something worth bargaining with. Say, for the last two thousand.”

“Oh aye? What is it? A motorcar?” The only thing worth the trouble these days, in Daniel’s opinion.

“Better,” Mortimer said. “A lady.”

Daniel hid a sigh. “I don’t need a courtesan. I can find women on me own.”

Easily. Daniel looked at ladies, and they came to him. Part of his charm, he knew, was his wealth; part was the fact that he belonged to the great Mackenzie family and was nephew to a duke. But Daniel never argued about the ladies’ motives; he simply enjoyed.

“She’s not a courtesan,” Mortimer said. “She’s special. You’ll see.”

An actress, perhaps. She’d give an indifferent performance of a Shakespearean soliloquy, and Daniel would be expected to smile and pronounce her worth every penny.

“Keep your money,” Daniel said. “Give me a horse or your best servant in lieu—I’m not particular.”

Mortimer’s friends didn’t move. “But I insist,” Mortimer said.

Eleven against one. If Daniel argued, he’d only end up with bruised knuckles. He didn’t particularly want to hurt his hands, because he had the fine-tuning of his engine to do, and he needed to be able to hold a spanner.

“Fair enough,” Daniel said. “But I assess the goods before I accept it as payment of debt.”

Mortimer agreed. He clapped Daniel on the shoulder as he led him out, and Daniel stopped himself shaking off his touch.

Mortimer’s friends filed around them in a defensive flank as they made their way to Mortimer’s waiting landau. Daniel noted as they pulled away from the Nines that the bone-breaker had slipped out the door behind them and followed.

Mortimer took Daniel through the misty city to a respectable neighborhood north of Oxford Street, stopping on a quiet lane near Portman Square.

The hour was two in the morning, and this street was silent, the houses dark. Behind the windows lay respectable gentlemen who would rise in the early hours and trundle to the City for work.

Daniel descended from the landau and looked up at the dark windows. “She’ll be asleep, surely. Leave it for tomorrow.”

“Nonsense,” Mortimer said. “She sees me anytime I call.”

He walked to a black-painted front door and rapped on it with his stick. Above them a light appeared, and a curtain drew back. Mortimer looked up at the window, made an impatient gesture, and rapped on the door again.

The curtain dropped, and the light faded. Tap, tap, tap, went Mortimer’s stick. Daniel folded his arms, stopping himself from ripping the stick from Mortimer’s hands and breaking it over his knee. “Who lives here?”

“I do,” Mortimer said. “I mean, I own the house. At least, my family does. We let it to Madame Bastien and her daughter. For a slight savings in rent, they agreed to entertain me and my friends anytime I asked it.”

“Including the middle of the bloody night?”

“Especially the middle of the night.”

Mortimer smiled—self-satisfied English prig. The ladies inside had to be courtesans. Mortimer had reduced the rent and obligated them to pay in kind.

Daniel turned back to the landau. “This isn’t worth two thousand, Mortimer.”

“Patience. You’ll see.”

The rest of Mortimer’s friends had arrived and hemmed them in, blocking the way back to the landau. The bone-breaker was still in attendance, hovering in the shadows a little way down the street.

The door opened. A maid who’d obviously dressed hastily stepped aside and let the stream of gentlemen inside. The drunker lads of the party wanted to pause to see what entertainment she might provide, but Daniel planted himself solidly beside the door, blocking their way to her. They moved past, forgetting about her.

Mortimer led the way to double pocket doors at the end of the hall and pushed them open. Daniel caught a flurry of movement from the room beyond, but by the time Mortimer beckoned Daniel, stillness had taken over.

They entered a dining room. The walls were covered with a blue, gold, and burnt orange striped wallpaper, its many colors bright in the light of a hearth fire. A gas chandelier hung dark above, and a solitary candelabra with three candles rested on the long, empty table. A young woman was just touching a match to the candlewicks.

When the third candle was lit, she blew out the match and straightened up. “So sorry to have kept you waiting, gentlemen,” she said in a voice very faintly accented. “I’m afraid my mother is unable to rise. You will have to make do with me.”

Whatever Mortimer and the other gentlemen said in response, Daniel didn’t hear. He couldn’t hear anything. He couldn’t see anything either, except the woman who stood poised behind the candelabra, the long match still in her hand, the smile of an angel on her face.

She wasn’t beautiful. Daniel had seen faces more beautiful in the Casino in Monte Carlo, at the Moulin Rouge in Paris. He’d known slimmer bodies in dancers, or in the butterflies that glided about the gaming hells in St. James’s and Monaco, enticing gentlemen to play.

This young woman had an angular face softened by a mass of dark hair dressed in a pompadour, ringlets trickling down the sides of her face. Her nose was a little too long, her mouth too wide, her shoulders and arms too plump. Her eyes were her best feature, set in exact proportion in her face, dark blue in the glint of candlelight.

They were eyes a man could gaze into all night and wake up to in the morning. He could contemplate her eyes across the breakfast table and then at dinner while he made plans to look into them again all through the night.

She wasn’t a courtesan. Courtesans began charming the moment a gentleman walked into a room. They gestured with graceful fingers, implying that those fingers would be equally graceful traveling a man’s body. Courtesans drew in, they suggested without words, they used every movement and every expression to beguile.

This woman stood fixed in place, her body language not inviting the gentlemen into the room at all, despite her words and her smile. If her movements were graceful as she turned to toss the match into the fire, it was from nature, not practice.

She wore a plain gown of blue satin that bared her shoulders, but the gown was no less respectable than what a lady in this neighborhood might wear for dinner or a night at the theatre. Her hair in the simple pompadour had no ribbons or jewels to adorn it. The unaffected style hinted that the dark masses might come down at any time over the hands of the lucky gentleman who pulled out the hairpins.

The young woman spread her hands at the now silent men. “If you’ll sit, gentlemen, we can begin.”

Daniel couldn’t move. His feet had grown into the floor, disobedient to his will. They wanted him to stand in that place all night long and gaze upon this woman.

Mortimer leaned to Daniel. “You see? Did I not tell you she’d be worth it?” He cleared his throat. “Daniel Mackenzie, may I introduce Mademoiselle Bastien. Violette is her Christian name, in the French way. Mademoiselle, this is Daniel Mackenzie, son of Lord Cameron Mackenzie and nephew to the Duke of Kilmorgan. You’ll give him a fine show, won’t you? There’s a good girl.”

As the man called Daniel Mackenzie came around the table and boldly stepped next to Violet, her breath stopped. Mr. Mackenzie did nothing but look at her and hold out his hand in greeting. And yet, every inch of Violet’s flesh tingled at his nearness, every breath threatened to choke her.

Scottish, Violet thought rapidly, taking in his blue and green plaid kilt under the fashionable black suit coat and ivory waistcoat. Rich, noting the costly materials and the way in which the coat hugged his broad shoulders. Tailor-made, and not by a cheap or apprentice tailor. A master had designed and sewn those clothes. Mr. Mackenzie was used to the very best.

He topped most of the other gentlemen here by at least a foot, had a hard face, a nose that would be large on any other man, and eyes that made her stop. Violet couldn’t decide the color of them in this light—hazel? brown?—but they were arresting. So arresting that she stood staring at him, not taking the hand he held out to her.

“Daniel Mackenzie, at your service, Mademoiselle.”

He gave her a light, charming smile, his eyes pulling her in, keeping her where he wanted her.

Definitely danger here.

Old terror stirred, but Violet pushed it down. She couldn’t afford to go to pieces right now. She’d come down here to placate Mortimer, letting her mother, who’d nearly had hysterics when Mortimer had started pounding on the door, stay safely upstairs. Violet, who could handle a crowd of several hundred angry men and women shouting for blood, could certainly cope with less than a dozen half-drunk Mayfair gentlemen in the middle of the night.

Mr. Mackenzie was only another of Mortimer’s vapid friends. Violet saw the barrier behind Mr. Mackenzie’s eyes, though, when she risked a look into them. This man gave up his secrets to very few. He would be difficult to read, which could be a problem.

Mr. Mackenzie waited, his hand out. Violet finally slid hers into his gloved one, making the movement slow and deliberate.

“How do you do,” she said formally, her English perfect. She’d discovered long ago that speaking flawless English reinforced the fiction that she was entirely French.

Daniel closed his large hand around hers and raised it to his lips. “Enchanted.”

The quick, hot brush of his mouth to the backs of her fingers ignited a spark to rival that on the match she’d tossed away. Violet’s nerves tightened like wires, forcing the deep breath she’d been trying not to take.

The little gasp sounded loud to her, but Mortimer’s cronies were making plenty of noise as they shed coats and debated where each would sit.

Daniel’s gaze fixed on Violet over her hand, challenging, daring. Show me who you are, that gaze said.

Violet was supposed to be thinking that about him. Whatever the world believed about the talents of Violette Bastien, medium and spiritualist, she knew her true gift was reading people.

Within a few moments of studying a man, Violet could understand what he loved and what he hated, what he wanted with all his heart and what he’d do to get it. She’d learned these lessons painstakingly from Jacobi in the backstreets of Paris, had been his best pupil.

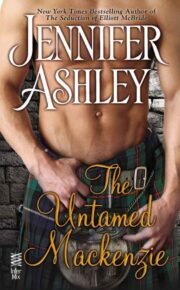

"The Untamed Mackenzie" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "The Untamed Mackenzie". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "The Untamed Mackenzie" друзьям в соцсетях.