And she was not yet old enough to want to rule alone. The crown was unsteady on her head, the country was filled with her enemies. She was a young woman, only twenty-five years old, with neither mother nor father nor a beloved family to advise her. She needed to be surrounded by friends whom she could trust: Cecil, her teacher Roger Ascham, her former governess Kat Ashley, and her plump, gossipy cofferrer Thomas Parry with his wife Blanche, who had been Elizabeth’s nanny. Now that Elizabeth was queen she did not forget those who had been faithful to her when she had been princess, and there was not one old friend who was not now enjoying a small fortune in rich repayment for the years of waiting.

Why, she actually prefers the company of inferiors, Dudley thought, looking from Cecil at the table to Kat Ashley at the window. She was brought up by servants and people of the middling sort and she prefers their values. She understands trade and good housekeeping and the value of a well-run estate because that is what they care about. While I was walking around the royal palaces and spending my time with my father commanding the court, she was fussing over the price of bacon and staying out of debt.

She is small scale, not a queen at all yet. She will stick at the raising of the Host because she can see it; that is real, it happens before her nose. But the great debates of the church she would rather avoid. Elizabeth has no vision; she has never had time to see beyond her own survival.

At the table, Cecil beckoned to one of his clerks and the man stepped forward and showed the young queen a page of writing.

If a man wanted to dominate this queen, he would have to separate her from Cecil, Robert thought to himself, watching the two heads so companionably close together as she read his paper. If a man wanted to rule England through this queen he would have to be rid of Cecil first. And she would have to lose faith in Cecil before anything else could be done.

Elizabeth pointed to something on the page; Cecil answered her question, and then she nodded her agreement. She looked up and, seeing Dudley’s eyes upon her, beckoned him forward.

Dudley, head up, a little swagger in his stride at stepping forward before the whole court, came up to the throne and swept a deep, elegant bow.

“Good day, Your Grace,” he said. “And God bless you in this first day of your rule.”

Elizabeth beamed at him. “We have been preparing the list of my emissaries to go to the courts of Europe to announce my coronation,” she said. “Cecil suggests that I send you to Philip of Spain in Brussels. Shall you like to tell your old master that I am now anointed queen?”

“As you wish,” he agreed at once, hiding his irritation. “But are you going to stay indoors at work all day today, Your Grace? Your hunter is waiting, the weather is fine.”

He caught her longing glance toward the window and her hesitation.

“The French ambassador…” Cecil remarked for her ear only.

She shrugged. “The ambassador can wait, I suppose.”

“And I have a new hunter that I thought you might try,” Dudley said temptingly. “From Ireland. A bright bay, a handsome horse, and strong.”

“Not too strong, I hope,” Cecil said.

“The queen rides like a Diana.” Dudley flattered her to her face, not even glancing at the older man. “There is no one to match her. I would put her on any horse in the stables and it would know its master. She rides like her father did, quite without fear.”

Elizabeth glowed a little at the praise. “I will come in an hour,” she said. “First, I have to see what these people want.” She glanced around the room and the men and women stirred like spring barley when the breeze passes over it. Her very glance could make them ripple with longing for her attention.

Dudley laughed quietly. “Oh, I can tell you that,” he said cynically. “It needn’t take an hour.”

She tipped her head to one side to listen, and he stepped up to the throne so that he could whisper in her ear. Cecil saw her eyes dance and how she put her hand to her mouth to hold in her laughter.

“Shush, you are a slanderer,” she said, and slapped the back of his hand with her gloves.

At once, Dudley turned his hand over, palm up, as if to invite another smack. Elizabeth averted her head and veiled her eyes with her dark lashes.

Dudley bent his head again, and whispered to her once more. A giggle escaped from the queen.

“Master Secretary,” she said. “You must send Sir Robert away, he is too distracting.”

Cecil smiled pleasantly at the younger man. “You are most welcome to divert Her Grace,” he said warmly. “If anything, she works too hard. The kingdom cannot be transformed in a week; there is much to do but it will have to be done over time. And…” He hesitated. “Many things we will have to consider carefully; they are new to us.”

And you are at a loss half the time, Robert remarked to himself. I would know what should be done. But you are her advisor and I am merely Master of Horse. Well, so be it for today. So I will take her riding.

Aloud he said with a smile: “There you are then! Your Grace, come out and ride with me. We need not hunt, we’ll just take a couple of grooms and you can try the paces of this bay horse.”

“Within the hour,” she promised him.

“And the French ambassador can ride with you,” Cecil suggested.

A swift glance from Robert Dudley showed that he realized he had been burdened with chaperones but Cecil’s face remained serene.

“Don’t you have a horse he can use in the stables?” he asked, challenging Robert’s competence, without seeming to challenge him at all.

“Of course,” Robert said urbanely. “He can have his pick from a dozen.”

The queen scanned the room. “Ah, my lord,” she said pleasantly to one of the waiting men. “How glad I am to see you at court.”

It was his cue for her attention and at once he stepped forward. “I have brought Your Grace a gift to celebrate your coming to the throne,” he said.

Elizabeth brightened; she loved gifts of any sort, she was as acquisitive as a magpie. Robert, knowing that what would follow would be some request for the right to cut wood or enclose common land, to avoid a tax or persecute a neighbor, stepped down from the dais, bowed, walked backward from the throne, bowed again at the door, and went out to the stables.

Despite the French ambassador, a couple of lords, some small-fry gentry, a couple of ladies-in-waiting, and half a dozen guards that Cecil had collected to accompany the queen, Dudley managed to ride by her side and they were left alone for most of the ride. At least two men muttered that Dudley was shown more favor than he deserved, but Robert ignored them, and the queen did not hear.

They rode westerly, slowly at first through the streets and then lengthening the pace of the horses as they entered the yellowing winter grassland of St. James’s Park. Beyond the park, the houses gave way to market gardens to feed the insatiable city, and then to open fields, and then to wilder country. The queen was absorbed in managing the new horse, who fretted at too tight a rein but would take advantage and toss his head if she let him ride too loose.

“He needs schooling,” she said critically to Robert.

“I thought you should try him as he is,” he said easily. “And then we can decide what is to be done with him. He could be a hunter for you, he is strong enough and he jumps like a bird, or he could be a horse you use in processions, he is so handsome and his color is so good. If you want him for that, I have a mind to have him specially trained, taught to stand and to tolerate crowds. I thought your gray fretted a little when people pushed very close.”

“You can’t blame him for that!” she retorted. “They were waving flags in his face and throwing rose petals at him!”

He smiled at her. “I know. But this will happen again and again. England loves her princess. You will need a horse that can stand and watch a tableau, and let you bend down and take a posy from a child without shifting for a moment, and then trot with his head up looking proud.”

She was struck by his advice. “You’re right,” she said. “And it is hard to pay attention to the crowd and to manage a horse.”

“I don’t want you to be led by a groom either,” he said decidedly. “Or to ride in a carriage. I want them to see you mastering your own horse. I don’t want anything taken away from you. Every procession should add to you; they should see you higher, stronger, grander even than life.”

Elizabeth nodded. “I have to be seen as strong; my sister was always saying she was a weak woman, and she was always ill, all the time.”

“And he is your color,” he said impertinently. “You are a bright chestnut yourself.”

She was not offended; she threw back her head and laughed. “Oh, d’you think he is a Tudor?” she asked.

“For sure, he has the temper of one,” Robert said. He and his brothers and sisters had been playmates in the royal nursery at Hatfield, and all the Dudley children had felt the ringing slap of the Tudor temper. “Doesn’t like the bridle, doesn’t like to be commanded, but can be gentled into almost anything.”

She gleamed at him. “If you are so wise with a dumb beast, let’s hope you don’t try to train me,” she said provocatively.

“Who could train a queen?” he replied. “All I could do would be to implore you to be kind to me.”

“Have I not been very kind already?” she said, thinking of the best post which she had given him, Master of Horse, with a massive annual income and the right to set up his own table at court and to take the best rooms in whichever palace the court might visit.

He shrugged as if it were next to nothing. “Ah, Elizabeth,” he said intimately. “That is not what I mean when I desire you to be kind to me.”

“You may not call me Elizabeth anymore,” she reminded him quietly, but he thought she was not displeased.

“I forgot,” he said, his voice very low. “I take such pleasure in your company that sometimes I think we are still just friends as we used to be. I forgot for a moment that you have risen to such greatness.”

“I was always a princess,” she said defensively. “I have risen to nothing but my birthright.”

“And I always loved you for nothing but yourself,” he replied cleverly.

He could see her hands loosen slightly on the reins and knew that he had struck the right note with her. He played her as every favorite plays every ruler; he had to know what charmed and what cooled her.

“Edward was always very fond of you,” she said softly, remembering her brother.

He nodded, looking grave. “God bless him. I miss him every day, as much as my own brothers.”

“But he was not so warm to your father,” she said rather pointedly.

Robert smiled down at Elizabeth as if nothing of their past lives could be counted against them: his family’s terrible treason against her family, her own betrayal of her half-sister. “Bad times,” he said generally. “And long ago. You and I have both been misjudged, and God knows, we have been punished enough. We have both served our time in the Tower, accused of treason. I used to think of you then; when I was allowed out to walk on the leads, I used to go to the very threshold of the gated door of your tower, and know that you were just on the other side. I’d have given much to be able to see you. I used to have news of you from Hannah the Fool. I can’t tell you what a comfort it was to know you were there. They were dark days for us both; but I am glad now that we shared them together. You on one side of that gate and me the other.”

“Nobody else can ever understand,” she said with suppressed energy. “Nobody can ever know unless you have been there: what it’s like to be in there! To know that below you, out of sight, is the green where the scaffold will be built, and not to know whether they are building it, sending to ask, and not trusting the answer, wondering if it will be today or tomorrow.”

“D’you dream of it?” he asked, his voice low. “Some nights I still wake up in terror.”

A glance from her dark eyes told him that she too was haunted. “I have a dream that I hear hammering,” she said quietly. “It was the sound I dreaded most in the world. To hear hammering and sawing and to know that they are building my own scaffold right underneath my window.”

“Thank God those days are done and we can bring justice to England, Elizabeth,” he said warmly.

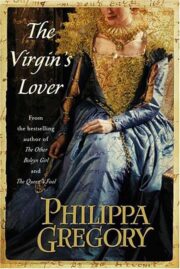

"The Virgin’s Lover" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "The Virgin’s Lover". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "The Virgin’s Lover" друзьям в соцсетях.