This time she did not correct him for using her name.

“We should turn for home, sir,” one of the grooms rode up to remind him.

“It is your wish?” he asked the queen.

She gave him a little inviting sideways smile. “D’you know, I should like to ride out all day. I am sick of Whitehall and the people who come, and every one of them wanting something. And Cecil with all the business that needs doing.”

“Why don’t we ride early tomorrow?” he suggested. “Ride out by the river, we can cross over to the south bank and gallop out through Lambeth marshes and not come home till dinner time?”

“Why, what ever will they say?” she asked, instantly attracted.

“They will say that the queen is doing as she wishes, as she should do,” he said. “And I shall say that I am hers to command. And tomorrow evening I shall plan a great feast for you with dancing and players and a special masque.”

Her face lit up. “For what reason?”

“Because you are young, and beautiful, and you should not go from schoolroom to lawmaking without taking some pleasure. You are queen now, Elizabeth, you can do as you wish. And no one can refuse you.”

She laughed at the thought of it. “Shall I be a tyrant?”

“If you wish,” he said, denying the many forces of the kingdom, which inevitably would dominate her: a young woman alone amidst the most unscrupulous families in Christendom. “Why not? Who should say “no” to you? The French princess, your cousin Mary, takes her pleasures, why should you not take yours?”

“Oh, her,” Elizabeth said irritably, a scowl crossing her face at the mention of Mary, Queen of Scots, the sixteen-year-old princess of the French court. “She lives a life of nothing but pleasure.”

Robert hid a smile at the predictable jealousy of Elizabeth for a prettier, luckier princess. “You will have a court that will make her sick with envy,” he assured her. “A young, unmarried, beautiful queen, in a handsome, merry court? There’s no comparison with Queen Mary, who is burdened with a husband, the Dauphin, and ruled by the Guise family, and spends all her life doing as they wish.”

They turned their horses for home.

“I shall devote myself to bringing you amusements. This is your time, Elizabeth; this is your golden season.”

“I did not have a very merry girlhood,” she conceded.

“We must make up for that now,” he said. “You shall be the pearl at the center of a golden court. The French princess will hear every day of your happiness. The court will dance to your bidding, this summer will be filled with pleasure. They will call you the golden princess of all of Christendom! The most fortunate, the most beautiful, and the most loved.”

He saw the color rise in her cheeks. “Oh, yes,” she breathed.

“But how you will miss me when I am at Brussels!” he slyly predicted. “All these plans will have to wait.”

He saw her consider it. “You must come home quickly.”

“Why not send someone else? Anyone can tell Philip you are crowned; it does not need to be me. And if I am not here, who will organize your banquets and parties?”

“Cecil thought you should go,” she said. “He thought it a pleasant compliment to Philip, to send him a man who had served in his armies.”

Robert shrugged. “Who cares what the King of Spain thinks now? Who cares what Cecil thinks? What d’you think, Elizabeth? Shall I go away for a month to another court at Brussels, or shall you keep me here to ride and dance with you, and keep you merry?”

He saw her little white teeth nip her lips to hide her pleased smile. “You can stay,” she said carelessly. “I’ll tell Cecil he has to send someone else.”

It was the dreariest month of the year in the English countryside, and Norfolk one of the dreariest counties of England. The brief flurry of snow in January had melted, leaving the lane to Norwich impassable by cart and disagreeable on horseback, and besides, there was nothing at Norwich to be seen except the cathedral; and now that was a place of anxious silences, not peace. The candles had been extinguished under the statue of the Madonna, the crucifix was on the altar still but the tapestries and the paintings had been taken down. The little messages and prayers which had been pinned to the Virgin’s gown had disappeared. No one knew if they were allowed to pray to Her anymore.

Amy did not want to see the church she had loved stripped bare of everything she knew was holy. Other churches in the city had been desanctified and were being used as stables, or converted into handsome town houses. Amy could not imagine how anyone could dare to put his bed where the altar had once stood; but the new men of this reign were bold in their own interests. The shrine at Walsingham had not yet been destroyed, but Amy knew that the iconoclasts would come against it some day soon, and then where would a woman pray who wanted to conceive a child? Who wanted to win back her husband from the sin of ambition? Who wanted to win him home once more?

Amy Dudley practiced her writing, but there seemed little point. Even if she could have managed a letter to her husband there was no news to give him, except what he would know already: that she missed him, that the weather was bad and the company dull, the evenings dark and the mornings cold.

On days such as this, and Amy had many days such as this, she wondered if she would have been better never to have married him. Her father, who adored her, had been against it from the start. The very week before her wedding he had gone down on his knee before her in the hall of Syderstone farmhouse, his big, round face flushed scarlet with emotion, and begged her with a quaver in his voice to think again. “I know he’s handsome, my bird,” he had said tenderly. “And I know he’ll be a great man, and his father is a great man, and the royal court itself is coming to see you wed at Sheen next week, an honor I never dreamed of, not even for my girl. But are you certain sure you want a great man when you could marry a nice lad from Norfolk and live near me, in a pretty little house I would build for you, and have my grandsons brought up as my own, and stay as my girl?”

Amy had put her little hands on his shoulders and raised him up, she had cried with her face tucked against his warm homespun jacket, and then she had looked up, all smiles, and said: “But I love him, Father, and you said that I should marry him if I was sure; and before God, I am sure.”

He had not pressed her—she was his only child from his first marriage, his beloved daughter, and he could never gainsay her. And she had been used to getting her own way. She had never thought that her judgment could be wrong.

She had been sure then that she loved Robert Dudley; indeed, she was sure now. It was not lack of love that made her cry at night as if she would never stop. It was excess of it. She loved him, and every day without him was a long, empty day. She had endured many days without him when he had been a prisoner and could not come to her. Now, bitterly, at the very moment of his freedom and his rise to power, it was a thousand times worse, because now he could come to her, but he chose not to.

Her stepmother asked her, would she join him at court when the roads were fit for travel? Amy stammered in her reply, and felt like a fool, not knowing what was to happen next, nor where she was supposed to go.

“You must write to him for me,” she said to Lady Robsart. “He will tell me what I am to do.”

“Do you not want to write yourself?” her stepmother prompted. “I could write it out for you and you could copy it.”

Amy turned her head away. “What’s the use?” she asked. “He has a clerk read it to him anyway.”

Lady Robsart, seeing that Amy was not to be tempted out of bad temper, took a pen and a piece of paper, and waited.

“My lord,” Amy started, the smallest quaver in her voice.

“We can’t write ‘my lord,’ ” her stepmother expostulated. “Not when he lost the title for treason, and it has not been restored him.”

“I call him my lord!” Amy flared up. “He was Lord Robert when he came to me, and he has always been Lord Robert to me, whatever anyone else calls him.”

Lady Robsart raised her eyebrows as if to say that he was a poor job when he came to her, and was a poor job still, but she wrote the words, and then paused, while the ink dried on the sharpened quill.

“I do not know where you would wish me to stay. Shall I come to London?” Amy said in a voice as small as a child’s. “Shall I join you in London, my lord?”

All day Elizabeth had been on tenterhooks, sending her ladies to see if her cousin had entered the great hall, sending pageboys to freeze in the stable yard so that her cousin could be greeted and brought to her presence chamber at once. Catherine Knollys was the daughter of Elizabeth’s aunt, Mary Boleyn, and had spent much time with her young cousin Elizabeth. The girls had formed a faithful bond through the uncertain years of Elizabeth’s childhood. Catherine, nine years Elizabeth’s senior, an occasional member of the informal court of children and young people who had gathered around the nursery of the young royals at Hatfield, had been a kindly and generous playmate when the lonely little girl had sought her out, and as Elizabeth became older, they found they had much in common. Catherine was a highly educated girl, a Protestant by utter conviction. Elizabeth, less convinced and with much more to lose, had always had a sneaking admiration for her cousin’s uncompromising clarity.

Catherine had been with Elizabeth’s mother, Anne Boleyn, in the last dreadful days in the Tower. She held, from that day on, an utter conviction of her aunt’s innocence. Her quiet assertion that Elizabeth’s mother was neither whore nor witch, but the victim of a court plot, was a secret comfort to the little girl whose childhood had been haunted by slanders against her mother. The day that Catherine and her family had left England, driven out by Queen Mary’s anti-heresy laws, Elizabeth had declared that her heart was broken.

“Peace. She will be here soon,” Dudley assured her, finding Elizabeth pacing from one window in Whitehall Palace to another.

“I know. But I thought she would be here yesterday, and now I am worrying that it will not be till tomorrow.”

“The roads are bad; but she will surely come today.”

Elizabeth twisted the fringe of the curtain in her fingers and did not notice that she was shredding the hem of the old fabric. Dudley went beside her and gently took her hand. There was a swiftly silenced intake of breath from the watching court at his temerity. To take the queen’s hand without invitation, to disentangle her fingers, to take both her hands firmly in his own, and give her a little shake!

“Now, calm down,” Dudley said. “Either today or tomorrow, she will be here. D’you want to ride out on the chance of meeting her?”

Elizabeth looked at the iron-gray sky that was darkening with the early twilight of winter. “Not really,” she admitted unwillingly. “If I miss her on the way then it will only make the wait longer. I want to be here to greet her.”

“Then sit down,” he commanded. “And call for some cards and we can play until she gets here. And if she does not get here today we can play until you have won fifty pounds off me.”

“Fifty!” she exclaimed, instantly diverted.

“And you need stake nothing more than a dance after dinner,” he said agreeably.

“I remember men saying that they lost fortunes to entertain your father,” William Cecil remarked, coming up to the table as the cards were brought.

“Now he was a gambler indeed,” Dudley concurred amiably. “Who shall we have for a fourth?”

“Sir Nicholas.” The queen looked around and smiled at her councillor. “Will you join us for a game of cards?”

Sir Nicholas Bacon, Cecil’s corpulent brother-in-law, swelled like a mainsail at the compliment from the queen, and he stepped up to the table. The pageboy brought a fresh pack, Elizabeth dealt the stiff cards with their threatening faces, cut the deal to Robert Dudley, and they started to play.

There was a flurry in the hall outside the presence chamber, and then Catherine and Francis Knollys were in the doorway, a handsome couple: Catherine a woman in her mid-thirties, plainly dressed and smiling in anticipation, her husband an elegant man in his mid-forties. Elizabeth sprang to her feet, scattering her cards, and ran across the presence chamber to her cousin.

Catherine dropped into a curtsy but Elizabeth plunged into her arms and the two women hugged each other, both of them in tears. Sir Francis, standing back, smiled benignly at the welcome given to his wife.

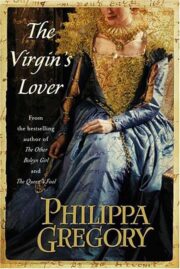

"The Virgin’s Lover" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "The Virgin’s Lover". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "The Virgin’s Lover" друзьям в соцсетях.