Her head came up at that, her dark eyes, Boleyn eyes, looked at him frankly. She smoothed her bronze hair under her cap. She smiled, that bewitching, sexually aware Boleyn smile. “How can I help it?” she asked him limpidly. “She only has to look at me to hate me.”

Later that night Cecil called for fresh candles and another log for the fire. He was writing to Sir James Croft, an old fellow-plotter. Sir James was at Berwick but Cecil had decided that the time had come for him to visit Perth.

Scotland is a tinderbox, he wrote in the code that he and Sir James had used to each other since Mary Tudor’s spy service had intercepted their letters, and John Knox is the spark that will set it alight. My commission for you is to go to Perth and do nothing more than observe. You should get there before the forces of the queen regent arrive. My guess is that you will see John Knox preaching the freedom of Scotland to an enthusiastic crowd. I should like to know how enthusiastic and how effective. You will have to make haste because the queen regent’s men may arrest him. He and the Scottish Protestant lords have asked for our help but I would know what sort of men they are before I commit the queen. Talk to them, take their measure. If they would celebrate their victory by turning the country against the French, and in alliance with us, they can be encouraged. And let me know at once. Information is a better coin than gold here.

Summer 1559

ROBERT FINALLY ARRIVED at Denchworth in the early days of June, all smiles and apologies for his absence. He told Amy that he could be excused from court for a few days since the queen, having formally refused the Archduke Ferdinand, was now inseparable from his ambassador, talking all the time about his master, and showing every sign of wishing to change her mind and marry him.

“She is driving Cecil mad,” he said, smiling. “No one knows what she intends or wants at all. She has refused him but now she talks about him all the time. She has no time for hunting, and no interest for riding. All she wants to do is to walk with the ambassador or practice her Spanish.”

Amy, with no interest in the flirtations of the queen or of her court, merely nodded at the news and tried to turn Robert’s attention to the property that she had found. She ordered horses from the stables for Robert, the Hydes, Lizzie Oddingsell, and for herself, and led the way on the pretty cross-country drover’s track to the house.

William Hyde found his way to Robert’s side. “What news of the realm?” he asked. “I hear that the bishops won’t support her.”

“They say they won’t take the oath confirming her as supreme governor,” Robert said briefly. “It is treason, as I tell her. But she is merciful.”

“What will she …er…mercifully do?” Mr. Hyde asked nervously, the burning days of Mary Tudor still very fresh in his memory.

“She’ll imprison them,” Robert said bluntly. “And replace them with Protestant clergy if she cannot find any Catholics to see reason. They have missed their chance. If they had called in the French before she was crowned they might have turned the country against her, but they have left it too late.” He grinned. “Cecil’s advice,” he said. “He had their measure. One after another of them will cave in or be replaced. They did not have the courage to rise against her with arms; they only stand against her on theological grounds, and Cecil will pick them off.”

“But she will destroy the church,” William Hyde said, shocked.

“She will break it down and make it new,” Dudley, the Protestant, said with pleasure. “She has been forced into a place where it is either the Catholic bishops or her own authority. She will have to destroy them.”

“Does she have the strength?”

Dudley raised a dark eyebrow. “It does not take much strength to imprison a bishop, as it turns out. She has half of them under house arrest already.”

“I mean strength of mind,” William Hyde said. “She is only a woman, even though a queen. Does she have the courage to go against them?”

Dudley hesitated. It was always everyone’s fear, since everyone knew that a woman could neither think nor do anything with any consistency. “She is well advised,” he said. “And her advisors are good men. We know what has to be done, and we keep her to it.”

Amy reined back her horse and joined them.

“Did you tell Her Grace that you were coming to look at a house?” she asked.

“Indeed yes,” he said cheerfully as they crested one of the rolling hills. “It’s been too long since the Dudleys had a family seat. I tried to buy Dudley Castle from my cousin, but he cannot bear to let it go. Ambrose, my brother, is looking for somewhere too. But perhaps he and his family could have a wing of this place. Is it big enough?”

“There are buildings that could be extended,” she said. “I don’t see why not.”

“And was it a monastic house, or an abbey or something?” he asked. “A good-sized place? You’ve told me nothing about it. I have been imagining a castle with a dozen pinnacles!”

“It’s not a castle,” she said, smiling. “But I think it is a very good size for us. The land is in good heart. They have farmed it in the old way, in strips, changing every Michaelmas, so it has not been exhausted. And the higher fields yield good grass for sheep, and there is a very pretty wood that I thought we might thin and cut some rides through. The water meadows are some of the richest I have ever seen, the milk from the cows must be almost solid cream. The house itself is a little too small, of course, but if we added a wing we could house any guests that we had…”

She broke off as their party rounded the corner in the narrow lane and Robert saw the farmhouse before him. It was long and low, an animal barn at the west end built of worn red brick and thatched in straw like the house, only a thin wall separating the beasts from the inhabitants. A small tumbling-down stone wall divided the house from the lane and inside it, a flock of hens scratched at what had once been a herb garden but was now mostly weeds and dust. To the side of the ramshackle building, behind the steaming midden, was a thickly planted orchard, boughs leaning down to the ground and a few pigs rooting around. Ducks paddled in the weedy pond beyond the orchard; swallows swooped from pond to barn, building their nests with beakfuls of mud.

The front door stood open, propped with a lump of rock. Robert could glimpse a low, stained ceiling and an uneven floor of stone slabs scattered with stale herbs but the rest of the interior was hidden in the gloom since there were almost no windows, and choked with smoke since there was no chimney but only a hole in the roof.

He turned to Amy and stared at her as if she were a fool, brought to beg for his mercy. “You thought that I would want to live here?” he asked incredulously.

“Just as I predicted,” William Hyde muttered quietly and pulled his horse gently away from the group, nodding to his wife for her to come with him, out of earshot.

“Why, yes,” Amy said, still smiling confidently. “I know the house is not big enough, but that barn could become another wing, it is high enough to build a floor in the eaves, just as they did at Hever, and then you have bedrooms above and a hall below.”

“And what plans did you have for the midden?” he demanded. “And the duck pond?”

“We would clear the midden, of course,” she said, laughing at him. “That would never do! It would be the first thing, of course. But we could spread it on the garden and plant some flowers.”

“And the duck pond? Is that to become an ornamental lake?”

At last she heard the biting sarcasm in his tone. She turned in genuine surprise. “Don’t you like it?”

He closed his eyes and saw at once the doll’s-house prettiness of the Dairy House at Kew, and the breakfast served by shepherdesses in the orchard with the tame lambs dyed green and white, skipping around the table. He thought of the great houses of his boyhood, of the serene majesty of Syon House, of Hampton Court, one of his favorite homes and one of the great palaces of Europe, of the Nonsuch at Sheen, or the Palace at Greenwich, of the walled solidity of Windsor, of Dudley Castle, his family seat. Then he opened his eyes and saw, once again, this place that his wife had chosen: a house built of mud on a plain of mud.

“Of course I don’t like it. It is a hovel,” he said flatly. “My father used to keep his sows in better sties than this.”

For once, she did not crumple beneath his disapproval. He had touched her pride, her judgment in land and property.

“It is not a hovel,” she replied. “I have been all over it. It is soundly built from brick and lathe and plaster. The thatch is only twenty years old. It needs more windows, for sure, but they are easily made. We would rebuild the barn, we would enclose a pleasure garden, the orchard could be lovely, the pond could be a boating lake, and the land is very good, two hundred acres of prime land. I thought it was just what we wanted, and we could make anything we want here.”

“Two hundred acres?” he demanded. “Where are the deer to run? Where is the court to ride?”

She blinked.

“And where will the queen stay?” he demanded acerbically. “In the henhouse, out the back? And the court? Shall we knock up some hovels on the other side of the orchard? Where will the royal cooks prepare her dinner? On that open fire? And where will we stable her horses? Shall they come into the house with us, as clearly they do at present? We can expect about three hundred guests; where do you think they will sleep?”

“Why should the queen come here?” Amy asked, her mouth trembling. “Surely she will stay at Oxford. Why should she want to come here? Why would we ask her here?”

“Because I am one of the greatest men at her court!” he exclaimed, slamming his fist down on the saddle and making his horse jump and then sidle nervously. He held it on a hard rein, pulling on its mouth. “The queen herself will come and stay at my house to honor me! To honor you, Amy! I asked you to find us a house to buy. I wanted a place like Hatfield, like Theobalds, like Kenninghall. Cecil goes home to Theobalds Palace, a place as large as a village under one roof; he has a wife who rules it like a queen herself. He is building Burghley to show his wealth and his grandeur; he is shipping in stonemasons from all over Christendom. I am a better man than Cecil, God knows. I come from stock that makes him look like a sheepshearer. I want a house to match his, stone for stone! I want the outward show that matches my achievements.

“For God’s sake, Amy, you’ve stayed with my sister at Penshurst! You know what I expect! I didn’t want some dirty farmhouse that we could clean up so that at its best, it was fit for a peasant to breed dogs in!”

She was trembling, hard put to keep her grip on the reins. From a distance, Lizzie Oddingsell watched and wondered if she should intervene.

Amy found her voice. She raised her drooping head. “Well, all very well, husband, but what you don’t know is that this farm has a yield of—”

“Damn the yield!” he shouted at her. His horse shied and he jabbed at it with a hard hand. It jibbed and pulled back, frightening Amy’s horse who stepped back, nearly unseating her. “I care nothing for the yield! My tenants can worry about the yield. Amy, I am going to be the richest man in England; the queen will pour the treasury of England upon me. I don’t care how many haystacks we can make from a field. I ask you to be my wife, to be my hostess at a house which is of a scale and of a grandeur—”

“Grandeur!” she flared up at him. “Are you still running after grandeur? Will you never learn your lesson? There was nothing very grand about you when you came out of the Tower, homeless and hungry; there was nothing very grand about your brother when he died of jail fever like a common criminal. When will you learn that your place is at home, where we might be happy? Why will you insist on running after disaster? You and your father lost the battle for Jane Grey, and it cost him his son and his own life. You lost Calais and came home without your brother and disgraced again! How low do you need to go before you learn your lesson? How base do you have to sink before you Dudleys learn your limits?”

He wheeled his horse and dug his spurs into its sides, wrenching it back with the reins. The horse stood up on its hind legs in a high rear, pawing the air. Robert sat in the saddle like a statue, reining back his rage and his horse with one hard hand. Amy’s horse shield away, frightened by the flailing hooves, and she had to cling to the saddle not to fall.

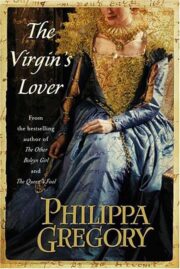

"The Virgin’s Lover" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "The Virgin’s Lover". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "The Virgin’s Lover" друзьям в соцсетях.