Cecil saw how his words, his very tone quietened her temper. He says “our” service? he remarked to himself. Am I serving him now?

“Let us withdraw with the Lord Secretary,” Dudley suggested. “And he can explain his decisions, and tell us how matters are in Scotland. He has had a long journey and an arduous task.”

She bridled; Cecil braced himself for more abuse.

“Come,” Dudley said simply, stretching out his hand to her. “Come, Elizabeth.”

He commands her by name before the whole court? Cecil demanded of himself in stunned silence.

But Elizabeth went to him, like a well-trained hound running in to heel, put her hand in his, and let him lead her from the hall. Dudley glanced back to Cecil and allowed himself the smallest smile. Yes, the smile said. Now you see how things are.

William Hyde summoned his sister to his office, the room where he transacted the business of his estate, a signal to her that the matter was a serious one and not to be confused by emotions or the claims of family ties.

He was seated behind the great rent table, which was circular and sectioned with drawers, each bearing a letter of the alphabet. The table could turn on its axis toward the landlord and each drawer had the contracts and rent books of the tenant farmers, filed under the initial letter of their name.

Lizzie Oddingsell remarked idly that the drawer marked “Z” had never been used, and wondered that no one thought to make a table which was missing the “X” and the “Z,” since these must be uncommon initial letters in English. Zebidee, she thought to herself. Xerxes.

“Sister, it is about Lady Dudley,” William Hyde started without preamble.

She noticed at once his use of titles for her and for her friend. So they were to conduct this conversation on the most formal footing.

“Yes, brother?” she replied politely.

“This is a difficult matter,” he said. “But to be blunt, I think it is time that you took her away.”

“Away?” she repeated.

“Yes.”

“Away to where?”

“To some other friends.”

“His lordship has made no arrangements,” she demurred.

“Have you heard from him at all?”

“Not since…” She broke off. “Not since he visited her in Norfolk.”

He raised his eyebrows, and waited.

“In March,” she added reluctantly.

“When she refused him a divorce and they parted in anger?”

“Yes,” she admitted.

“And since then you have had no letter? And neither has she?”

“Not that I know of…”She met his accusing look. “No, she has not.”

“Is her allowance being paid?”

Lizzie gave a little gasp of shock. “Yes, of course.”

“And your wages?”

“I am not waged,” she said with dignity. “I am a companion, not a servant.”

“Yes; but he is paying your allowance.”

“His steward sends it.”

“He has not quite cut her off then,” he said thoughtfully.

“He quite often fails to write,” she said stoutly. “He quite often does not visit. In the past it has sometimes been months…”

“He never fails to send his men to escort her from one friend to another,” he rejoined. “He never fails to arrange for her to stay at once place or another. And you say he has sent no one, and you have heard nothing since March.”

She nodded.

“Sister, you must take her and move on,” he said firmly.

“Why?”

“Because she is becoming an embarrassment to this house.”

Lizzie was quite bewildered. “Why? What has she done?”

“Leaving aside her excessive piety, which makes one wonder as to her conscience—”

“For God’s sake, brother, she is clinging to God as to life itself. She has no guilty conscience, she is just trying to find the will to live!”

He raised his hand. “Elizabeth, please. Let us stay calm.”

“I don’t know how to stay calm when you call this unhappy woman an embarrassment to you!”

He rose to his feet. “I will not have this conversation unless you promise me that you will stay calm.”

She took a deep breath. “I know what you are doing.”

“What?”

“You are trying not to be touched by her. But she is in the most unhappy position, and you would make it worse.”

He moved toward the door as if to hold it open for her. Lizzie recognized the signs of her brother’s determination. “All right,” she said hastily. “All right, William. There is no need to be fierce with me. It is as bad for me as it is for you. Worse, actually.”

He returned to his seat. “Leaving aside her piety, as I said, it is the position she puts us in with her husband that concerns me.”

She waited.

“She has to go,” he said simply. “While I thought we were doing him a favor by having her here, protecting her from slander and scorn, awaiting his instructions, she was an asset to us. I thought he would be glad that she had found safe haven. I thought he would be grateful to me. But now I think different.”

She raised her head to look at him. He was her younger brother and she was accustomed to seeing him in two contradictory lights: one as her junior, who knew less of the world than she did; and the other as her superior: the head of the family, a man of property, a step above her on the chain that led to God.

“And what do you think now, brother?”

“I think he has cast her off,” he said simply. “I think she has refused his wish, and angered him, and she will not see him again. And, what is more important, whoever she stays with, will not see him again. We are not helping him with a knotty problem, we are aiding and abetting her rebellion against him. And I cannot be seen to do such a thing.”

“She is his wife,” Lizzie said flatly. “And she has done nothing wrong. She is not rebelling, she is just refusing to be cast aside.”

“I can’t help that,” David said. “He is now living as husband in all but name to the Queen of England. Lady Dudley is an obstacle to their happiness. I will not be head of a household where the obstacle to the happiness of the Queen of England finds refuge.”

There was nothing she could say to fault his logic and he had forbidden her to appeal to his heart. “But what is she to do?”

“She has to go to another house.”

“And then what?”

“To another, and to another, and to another, until she can agree with Sir Robert and make some settlement, and find a permanent home.”

“You mean until she is forced into a divorce and goes to some foreign convent, or until she dies of heartbreak.”

He sighed. “Sister, there is no need to play a tragedy out of this.”

She faced him. “I am not playing a tragedy. This is tragic.”

“This is not my fault!” he exclaimed in sudden impatience. “There is no need to blame me for this. I am stuck with the difficulty but it is none of my making!”

“Whose fault is it then?” she demanded.

He said the cruelest thing: “Hers. And so she has to leave.”

Cecil had three meetings with Elizabeth before she could be brought even to listen to him without interrupting and raging at him. The first two were with Dudley and a couple of other men in attendance, and Cecil had to bow his head while she tore into him, complained of his inattention to her business, of his neglect of his country, of his disregard for their pride, their rights, their finances. After the first meeting he did not try to defend himself, but wondered whose voice it was that came so shrill, from the queen’s reproachful mouth.

He knew it was Robert Dudley’s. Robert Dudley, of course; who stood back by the window, leaning against the shutter, looking down into the midsummer garden, and sniffed a pomander held to his nose with one slim white hand. Now and again he would shift his position, or breathe in lightly, or clear his throat, and at once the queen would break off and turn, as if to give way to him. If Robert Dudley had so much as a passing thought she assumed they would all be eager to hear it.

She adores him, Cecil thought, hardly hearing the detail of the queen’s complaints. She is in her first flush of love, and he is the first love of her womanhood. She thinks the sun shines from his eyes, his opinions are the only wisdom she can hear, his voice the only speech, his smile her only pleasure. It is pointless to complain, it is pointless to be angry with her folly. She is a young woman in the madness of first love and it is hopeless expecting her to exercise any kind of sensible judgment.

The third meeting, Cecil found the queen alone but for Sir Nicholas Bacon and two ladies in attendance. “Sir Robert has been delayed,” she said.

“Let us start without him,” Sir Nicholas smoothly suggested. “Lord Secretary, you were going through the terms of the treaty, and the detail of the French withdrawal.”

Cecil nodded and put his papers before them. For the first time the queen did not spring to her feet and stride away from the table, railing against him. She kept her seat and she looked carefully at the proposal for the French withdrawal.

Emboldened, Cecil ran through the terms of the treaty again, and then sat back in his chair.

“And do you really think it is a binding peace?” Elizabeth asked.

For a moment, it was as it had always been between the two of them. The young woman looked to the older man for his advice, trusting that he would serve her with absolute fidelity. The older man looked down into the little face of his pupil and saw her wisdom and her ability. Cecil had a sense of the world returning to its proper axis, of the stars recoiling to their courses, of the faint harmony of the spheres, of homecoming.

“I do,” he said. “They were much alarmed by the Protestant uprising in Paris, they will not want to risk any other ventures for now. They fear the rise of the Huguenots, they fear your influence. They believe that you will defend Protestants wherever they are, as you did in Scotland, and they think that Protestants will look to you. They will want to keep the peace, I am sure. And Mary, Queen of Scots, will not take up her inheritance in Scotland while she can live in Paris. She will put in another regent and command him to deal fairly with the Scots lords, according to the terms of the peace contract. They will keep Scotland in name only.”

“And Calais?” the queen demanded jealously.

“Calais is, and always has been, a separate issue,” he said steadily. “As we have all always known. But I think we should demand it back under the terms of the treaty of Cateau-Cambrésis, when their lease falls due, as agreed. And they are more likely to honor the agreement now than before. They have learned to fear us. We have surprised them, Your Grace; they did not think we had the resolve. They will not laugh at us again. They certainly will not lightly make war on you again.”

She nodded, and pushed the treaty toward him. “Good,” she said shortly. “You swear it was the very best you could do?”

“I was pleased to get so much.”

She nodded. “Thank God we are free from the threat of them. I wouldn’t like to go through this past year again.”

“Nor I,” said Sir Nicholas fervently. “It was a great gamble when you took us into war, Your Majesty. A brilliant decision.”

Elizabeth had the grace to smile at Cecil. “I was very brave and very determined,” she said, twinkling at him. “Don’t you think so, Spirit?”

“I am sure that if England ever again faces such an enemy, you will remember this time,” he said. “You will have learned what to do for the next time. You have learned how to play the king.”

“Mary never did so much,” she reminded him. “She never had to face an invasion from a foreign power.”

“No, indeed,” he agreed. “Her mettle was not tested as yours has been. And you were tested and not found wanting. You were your father’s daughter and you have earned the peace.”

She rose from the table. “I can’t think what is keeping Sir Robert,” she complained. “He promised me he would be here an hour ago. He has a new delivery of Barbary horses and he had to be there to see them arrive in case they had to be sent back. But he promised me he would come at once.”

“Shall we walk down to the stables to meet him?” Cecil suggested.

“Yes,” she said eagerly. She took his arm and they walked side by side, as they had walked so often before.

“Let’s take a turn in the garden first,” he suggested. “The roses have been wonderful this year. D’you know, Scotland is a full month behind in the garden?”

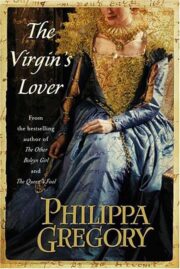

"The Virgin’s Lover" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "The Virgin’s Lover". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "The Virgin’s Lover" друзьям в соцсетях.