Ellen said nothing—the topic was one of idle curiosity only—and let Abby link their arms and lead her to the family dining room.

In the course of the meal, Ellen watched as Val consumed a tremendous quantity of good food, all the while conversing with the Belmonts about plans for his property, the boys’ upcoming matriculation, and mutual acquaintances. At the conclusion of the meal, Belmont offered Val and Ellen a tour of the property, and Abby departed on her husband’s arm to take her afternoon nap.

“May I offer you a turn through the back gardens while we wait for our host?” Val asked Ellen when the Belmonts had repaired abovestairs. “There’s plenty of shade, and I need to move lest I turn into a sculpture of ham and potatoes.”

He soon had her out the back door, her straw hat on her head. She wrapped her fingers around Val’s arm and pitched her voice conspiratorially low. “Find us some shade and a bench.”

He led her through gardens that were obviously the pride and joy of a man with a particular interest in flora, to a little gazebo under a spreading oak.

“Did we bore you at lunch with all of our talk of third parties and family ties?” he asked as he seated her inside the gazebo.

“Not at all, but you unnerved me with your familiar address.”

Val grimaced. “I hadn’t noticed. Suppose it’s best to go on as I’ve begun, though, unless you object? They aren’t formal people.”

“They are lovely people. Now sit you down, Mr. Windham, and take your medicine.” She withdrew her tin of comfrey salve, and Val frowned.

“You don’t have to do this.” He settled beside her on the bench that circled five interior sides of the hexagonal gazebo.

“Because you’ll be so conscientious about it yourself?” She’d positioned herself to his left and held out her right hand with an imperious wave. Taking Val’s left hand in her right, she studied it carefully.

“I didn’t get to see this the other night. It looks like it hurts.”

“Only when I use it. But if you’ll just hand me the tin, I can see to myself.”

“Stop being stubborn.” She dipped her fingers into the salve. “It’s only a hand, and only a little red and swollen. Maybe you shouldn’t be using it at all.” She began to spread salve over his knuckles while Val closed his eyes. “You have no idea why this has befallen you?”

“I might have overused it. Or it might be a combination of overuse and a childhood injury, or it might be just nerves.”

“Nerves?” Ellen peered over at him while she stroked her fingers over his palm. “One doesn’t usually attribute nerves to such hearty fellows as you.”

“It started the day I buried my second brother,” Val said on a sigh. He turned his head as if gazing out over the gardens or toward the manor house that sat so serenely on a small rise.

“You didn’t tell me you’d lost a brother.” She switched her grip so Val’s hand was between both of hers and her thumbs were circling on his broad and slightly callused palm.

“Two, actually. One on the Peninsula under less than heroic circumstances, though we don’t bruit that about, the other to consumption.” His voice could not have been more casual, but Ellen was holding his hand and felt the tension radiating from him.

“Valentine, I am so very sorry.”

“How did your husband die?” Val asked, desperately wanting to change the subject if not snatch his hand away and tear across the fields until he was out of sight.

“Fall from a horse.” Ellen said, though she did not turn loose of Val’s hand. “He lingered for two weeks, put his affairs in order—not that Francis’s affairs were ever out of order—then slipped away. I thought…”

“You thought?”

“I thought he was recovering.” She sighed, her fingers going still, though she kept his hand cradled in both of hers. “There was no outward injury, you see. He took a bump on the head, and there was some bruising around his middle, but no bleeding, no infection, nothing you’d think would kill a man.”

“He might have been bleeding inside. Or that bump on the head might have been what got him.”

“He was upset with himself to be incapacitated,” Ellen said softly. “The Markhams have bad hearts, you see. Their menfolk don’t often live past fifty, and some don’t live half that long. They are particularly careful of their succession, and so my failure to provide a son stood out in great relief. Francis was upset with himself for not seeing to his duty, not upset with me. His first wife had done no better than I, though, and that was some comfort.”

“I didn’t know you were a second wife,” Val said as Ellen shifted her ministrations to his wrist and forearm.

“She died of typhus. They were also married for five years, and I know Francis was very fond of her.”

“Fond.” Val winkled his nose at the term. “I suppose that’s genteel, but I can’t see myself spending the rest of my life with somebody of whom I am merely fond. I am fond of Ezekiel.”

“Your horse.” Ellen smiled at him. “He is fond of you, as well, but when you have nobody and nothing to be even fond of, then fond can loom like a great boon.”

“Nobody?” Val cocked his head, addressing her directly. “No cousins, no uncles or aunts, no old granny knitting in some kitchen?”

Ellen shook her head. “I was the only child of only children and born to them late in life. The present generation of Markhams was not prolific either. There’s Frederick, of course, and some theoretical cousin who enjoys the status of Frederick’s heir, but I do not relish Frederick’s company, and I’ve never met the cousin.”

“What is a theoretical cousin?”

“Francis called him that,” Ellen said, switching to long, slow strokes along Val’s forearm. It was a peculiarly soothing way to be touched, though Val had the sense she’d all but forgotten what her hands were doing. “I gather Mr. Grey might be joined so far back to the family tree as to make the connection suspect, or he might have been born to his mother long after she’d separated from Mr. Grey.”

“May I ask you a question?”

“Of course.” Ellen smiled at him again, the smile reaching her eyes this time. “We are holding hands in a location likely chosen to shield us from the prying eyes of our host and hostess.”

Val smiled back. “I am found out, though since when does it take an hour to escort one’s wife abovestairs?”

“I don’t begrudge them their marital bliss, or a lady in an interesting condition her rest.”

“If rest is what she’s getting.”

“Your question?”

“Why don’t you use the Markham name? You go by Ellen FitzEngle, when in fact you are Baroness Roxbury, and not even the dowager baroness, since Frederick hasn’t remarried.”

“FitzEngle was my mother’s maiden name,” Ellen said, her grip shifting back down to his palm and knuckles. “I wanted no associations with the Roxbury barony when I moved to Little Weldon, and there are few who know exactly to whom I was married.”

“Why? Were you ashamed of the connection?”

“I was ashamed of myself. I failed my husband in the one duty a wife is expected to perform. I did not want anybody’s pity or their scorn. My privacy means a lot to me.”

“But you dissemble,” Val said gently. “You are entitled to the respect of your position, and yet you labor all day in those gardens as if you have no portion, no connections, no place in society.”

Val tightened his fingers around hers when she would have drawn away. “You haven’t any portion, have you? No dower property. Why, Ellen? You speak of your husband as if he were some kind of saint, and yet even when he had time to put his affairs in order, he did not provide for you.”

“You will not speak ill of my husband. He provided for me.”

Secrets had a particular scent all their own, an unpleasant, cloying sweetness from being held too closely and carrying more power than they should. Val admitted he himself was keeping secrets from the woman beside him—the secret of his father’s ducal title, the secret of his musical ability—his former musical ability. Ellen wasn’t simply hiding her own title, however. She was hiding an entire past from an entire village.

“I did not mean to impugn Francis,” Val said carefully, turning his hand over to stroke his thumb over Ellen’s wrist. “I am concerned for you.”

“My situation is adequate for the present. Your concern is misplaced.”

His concern was not misplaced, though neither was it appreciated. A change of topic was in order. “Are you done with my hand, or might I convince you to hold on to it as we admire Axel’s gardens?”

“You might.” Ellen rose, and Val escorted her along a shady, winding path. He counted himself lucky, because she did indeed keep hold of his hand as she turned the topic. “Does this place give you ideas about your own grounds?”

“It does.” Val understood the conversation must not stray back to the personal until Ellen had her emotional balance. “The first such idea is that my estate needs a name. It will be the old Markham place until fifty years after I hang something else on the gateposts.”

“What comes to mind?”

“Nothing. And I don’t want to force a name on the place when names and labels have a way of becoming permanent.”

“What does the estate signify to you?” Ellen asked, keeping his fingers loosely linked with her own.

Val pursed his lips in thought. “Hard work. A summer project, an escape.” A dalliance.

He didn’t say that, of course. He wasn’t sure it was true. When he’d risen that morning and seen Darius departing on his piebald gelding, Val had felt a measure of relief to think the weekend would be spent in company. Somehow, sitting on Ellen’s porch in the evening darkness, he’d opened the topic of a different relationship with Ellen—a dalliance.

He’d meant to apologize for a year-old kiss, maybe, or to kiss her again. He wasn’t sure which, but he certainly hadn’t intended to baldly proposition the lady.

The matter had arisen unbidden, without Val planning to broach it. In his view, women as intimate partners were lovely creatures, like birds or pets or pretty house plants. They graced his life but were hardly necessary to it. When the occasional urge arose, he often felt it as a distraction from his music, indulging his sexual proclivities as an afterthought or an aside between the more fascinating business to be transacted at his keyboard.

He liked sex—he liked it a lot—but he seldom went in search of it.

And thus, he mused, he was probably no damned good at comprehending when he needed what Nick called a friendly poke, or how to arrange it with a minimum of fuss.

“You are quiet,” Ellen said. “Do you think of your brothers?”

“Every day,” Val said on a resigned sigh. It appeared they were going to brush up against this most uncomfortable topic again.

“It will get better,” Ellen assured him. “If it hasn’t already. You don’t just think of the loss, you also think of the good times and the gifts they left you with. You see the whole picture on your good days, and the ache fades.”

“Maybe. But it felt like I was just getting to that place with Bart’s death, which was stupid and avoidable, when Victor’s decline became impossible to ignore. And Victor and I had grown closer when Bart and Dev went off to war.”

She was silent for a moment as they strolled along. “I have pouted because I was an only child, but I never did consider what an affront it would be to lose siblings, particularly siblings in their prime, and siblings I was close to. I am sorry, Valentine, for your losses.”

He stopped walking, the emotional breath knocked out of him for reasons he could not consider. He’d heard the same platitude a thousand times before—two thousand—and knew the polite replies, but now Ellen’s arms went around his waist, and the polite replies choked him. Slowly, tentatively, he wrapped an arm, then two, around her shoulders, closed his eyes, and rested his cheek against her hair.

Frederick Markham was angry, and when he was angry his digestion became dyspeptic, which made him angrier still. A fellow needed the comforts of good food and fine spirits to soothe him when aggravations such as petty debts plagued him.

God damn Cousin Francis. With each passing quarter, the indignity of the late baron’s scheme became harder to bear. If it weren’t for the rents Ellen had passed along from Little Weldon, there would have been no hunting in the shires the previous winter. Even with burdensome economies, the Season itself had been cramped. Now, Frederick had tarried too long in Town, and there was no convenient house party to entertain him as summer got under way.

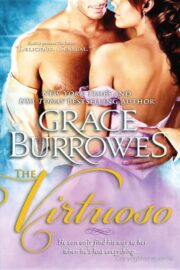

"The Virtuoso" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "The Virtuoso". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "The Virtuoso" друзьям в соцсетях.