“He left you these two sons?” He smiles down at my boys.

“The best part of my fortune,” I say. “This is Richard and this is Thomas Grey.”

He nods at my boys, who gaze up at him as if he were some kind of high-bred horse, too big for them to pet but a figure for awestruck admiration, and then he looks back to me. “I am thirsty,” he says. “Is your home near here?”

“We would be honored . . .” I glance at the guard who rides with him. There must be more than a hundred of them. He chuckles. “They can ride on,” he decides. “Hastings!” The older man turns and waits. “You go on to Grafton. I will catch you up. Smollett can stay with me, and Forbes. I will come in an hour or so.”

Sir William Hastings looks me up and down as if I am a pretty piece of ribbon for sale. I show him a hard stare in reply, and he takes off his hat and bows to me, throws a salute to the king, shouts to the guard to mount up.

“Where are you going?” he asks the king.

The boy-king looks at me.

“We are going to the house of my father, Baron Rivers, Sir Richard Woodville,” I say proudly, though I know the king will recognize the name of a man who was high in the favor of the Lancaster court, fought for them, and once took hard words from him in person when York and Lancaster were daggers drawn. We all know of one another well enough, but it is a courtesy generally observed to forget that we were all loyal to Henry VI once, until these turned traitor.

Sir William raises his eyebrow at his king’s choice for a stopping place. “Then I doubt that you’ll want to stay very long,” he says unpleasantly, and rides on. The ground shakes as they go by, and they leave us in warm quietness as the dust settles.

“My father has been forgiven and his title restored,” I say defensively. “You forgave him yourself after Towton.”

“I remember your father and your mother,” the king says equably. “I have known them since I was a boy in good times and bad. I am only surprised that they never introduced me to you.”

I have to stifle a giggle. This is a king notorious for seduction. Nobody with any sense would let their daughter meet him. “Would you like to come this way?” I ask. “It is a little walk to my father’s house.”

“D’you want a ride, boys?” he asks them. Their heads bob up like imploring ducklings. “You can both go up,” he says, and lifts Richard and then Thomas into the saddle. “Now hold tight. You on to your brother and you—Thomas, is it?—you hold on to the pommel.”

He loops the rein over his arm and then offers me his other arm, and so we walk to my home, through the wood, under the shade of the trees. I can feel the warmth of his arm through the slashed fabric of his sleeve. I have to stop myself leaning towards him. I look ahead to the house and to my mother’s window and see, from the little movement behind the mullioned panes of glass, that she has been looking out, and willing this very thing to happen.

She is at the front door as we approach, the groom of the household at her side. She curtseys low. “Your Grace,” she says pleasantly, as if the king comes to visit every day. “You are very welcome to Grafton Manor.”

A groom comes running and takes the reins of the horse to lead it to the stable yard. My boys cling on for the last few yards, as my mother steps back and bows the king into the hall. “Will you take a glass of small ale?” she asks. “Or we have a very good wine from my cousins in Burgundy?”

“I’ll take the ale, if you please,” he says agreeably. “It is thirsty work riding. It is hot for spring. Good day to you, Lady Rivers.”

The high table in the great hall is laid with the best glasses and a jug of ale as well as the wine. “You are expecting company?” he asks.

She smiles at him. “There is no man in the world could ride past my daughter,” she says. “When she told me she wanted to put her own case to you, I had them draw the best of our ale. I guessed you would stop.”

He laughs at her pride, and turns to smile at me. “Indeed, it would be a blind man who could ride past you,” he says.

I am about to make some little comment, but again it happens. Our eyes meet, and I can think of nothing to say to him. We just stand, staring at each other for a long moment, until my mother passes him a glass and says quietly, “Good health, Your Grace.”

He shakes his head, as if awakened. “And is your father here?” he asks.

“Sir Richard has ridden over to see our neighbors,” I say. “We expect him back for his dinner.”

My mother takes a clean glass and holds it up to the light and tuts as if there is some flaw. “Excuse me,” she says, and leaves. The king and I are alone in the great hall, the sun pouring through the big window behind the long table, the house in silence, as if everyone is holding their breath and listening.

He goes behind the table and sits down in the master’s chair. “Please sit,” he says, and gestures to the chair beside him. I sit as if I am his queen, on his right hand, and I let him pour me a glass of small ale. “I will look into your claim for your lands,” he says. “Do you want your own house? Are you not happy living here with your mother and father?”

“They are kind to me,” I say. “But I am used to my own household, I am accustomed to running my own lands. And my sons will have nothing if I cannot reclaim their father’s lands. It is their inheritance. I must defend my sons.”

“These have been hard times,” he says. “But if I can keep my throne, I will see the law of the land running from one coast of England to another once more, and your boys will grow up without fear of warfare.”

I nod my head.

“Are you loyal to King Henry?” he asks me. “D’you follow your family as loyal Lancastrians?”

Our history cannot be denied. I know that there was a furious quarrel in Calais between this king, then nothing more than a young York son, and my father, then one of the great Lancastrian lords. My mother was the first lady at the court of Margaret of Anjou; she must have met and patronized the handsome young son of York a dozen times. But who would have known then that the world might turn upside down and that the daughter of Baron Rivers would have to plead to that very boy for her own lands to be restored to her? “My mother and father were very great at the court of King Henry, but my family and I accept your rule now,” I say quickly.

He smiles. “Sensible of you all, since I won,” he says. “I accept your homage.”

I give a little giggle, and at once his face warms. “It must be over soon, please God,” he says. “Henry has nothing more than a handful of castles in lawless northern country. He can muster brigands like any outlaw, but he cannot raise a decent army. And his queen cannot go on and on bringing in the country’s enemies to fight her own people. Those who fight for me will be rewarded, but even those who have fought against me will see that I shall be just in victory. And I will make my rule run, even to the north of England, even through their strongholds, up to the very border of Scotland.”

“Do you go to the north now?” I ask. I take a sip of small ale. It is my mother’s best but there is a tang behind it; she will have added some drops of a tincture, a love philter, something to make desire grow. I need nothing. I am breathless already.

“We need peace,” he says. “Peace with France, peace with the Scots, and peace from brother to brother, cousin to cousin. Henry must surrender; his wife has to stop bringing in French troops to fight against Englishmen. We should not be divided anymore, York against Lancaster: we should all be Englishmen. There is nothing that sickens a country more than its own people fighting against one another. It destroys families; it is killing us daily. This has to end, and I will end it. I will end it this year.”

I feel the sick fear that the people of this country have known for nearly a decade. “There must be another battle?”

He smiles. “I shall try to keep it from your door, my lady. But it must be done and it must be done soon. I pardoned the Duke of Somerset and took him into my friendship, and now he has run away to Henry once more, a Lancastrian turncoat, faithless like all the Beauforts. The Percys are raising the north against me. They hate the Nevilles, and the Neville family are my greatest allies. It is like a dance now: the dancers are in their place; they have to do their steps. They will have a battle; it cannot be avoided.”

“The queen’s army will come this way?” Though my mother loved her and was the first of her ladies, I have to say that her army is a force of absolute terror. Mercenaries, who care nothing for the country; Frenchmen who hate us; and the savage men of the north of England who see our fertile fields and prosperous towns as good for nothing but plunder. Last time she brought in the Scots on the agreement that anything they stole they could keep as their fee. She might as well have hired wolves.

“I shall stop them,” he says simply. “I shall meet them in the north of England and I shall defeat them.”

“How can you be so sure?” I exclaim.

He flashes a smile at me, and I catch my breath. “Because I have never lost a battle,” he says simply. “I never will. I am quick on the field, and I am skilled; I am brave and I am lucky. My army moves faster than any other; I make them march fast and I move them fully armed. I outguess and I outpace my enemy. I don’t lose battles. I am lucky in war as I am lucky in love. I have never lost in either game. I won’t lose against Margaret of Anjou; I will win.”

I laugh at his confidence, as if I am not impressed; but in truth he dazzles me.

He finishes his cup of ale and gets to his feet. “Thank you for your kindness,” he says.

“You’re going? You’re going now?” I stammer.

“You will write down for me the details of your claim?”

“Yes. But—”

“Names and dates and so on? The land that you say is yours and the details of your ownership?”

I almost clutch his sleeve to keep him with me, like a beggar. “I will, but—”

“Then I will bid you adieu.”

There is nothing I can do to stop him, unless my mother has thought to lame his horse.

“Yes, Your Grace, and thank you. But you are most welcome to stay. We will dine soon . . . or—”

“No, I must go. My friend William Hastings will be waiting for me.”

“Of course, of course. I don’t wish to delay you . . .”

I walk with him to the door. I am anguished at his leaving so abruptly, and yet I cannot think of anything to make him stay. At the threshold he turns and takes my hand. He bows his fair head low and, deliciously, turns my hand. He presses a kiss into my palm and folds my fingers over the kiss as if to keep it safe. When he comes up smiling, I see that he knows perfectly well that this gesture has made me melt and that I will keep my hand clasped until bedtime when I can put it to my mouth.

He looks down at my entranced face, at my hand that stretches, despite myself, to touch his sleeve. Then he relents. “I shall fetch the paper that you prepare, myself, tomorrow,” he says. “Of course. Did you think differently? How could you? Did you think I could walk away from you, and not come back? Of course I am coming back. Tomorrow at noon. Will I see you then?”

He must hear my gasp. The color rushes back into my face so that my cheeks are burning hot. “Yes,” I stammer. “T . . . tomorrow.”

“At noon. And I will stay to dinner, if I may.”

“We will be honored.”

He bows to me and turns and walks down the hall, through the wide-flung double doors and out into the bright sunlight. I put my hands behind me and I hold the great wooden door for support. Truly, my knees are too weak to hold me up.

“He’s gone?” my mother asks, coming quietly through the little side door.

“He’s coming back tomorrow,” I say. “He’s coming back tomorrow. He’s coming back to see me tomorrow.”

When the sun is setting and my boys are saying their evening prayers, blond heads on their clasped hands at the foot of their trestle beds, my mother leads the way out of the front door of the house and down the winding footpath to where the bridge, a couple of wooden planks, spans the River Tove. She walks across, her conical headdress brushing the overhanging trees, and beckons me to follow her. At the other side, she puts her hand on a great ash tree, and I see there is a dark thread of silk wound around the rough-grained wood of the thick trunk.

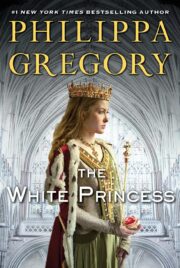

"The White Princess" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "The White Princess". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "The White Princess" друзьям в соцсетях.