“My daughter is well and happy, and is your most obedient servant,” my mother says pleasantly, in the little silence.

“And what motto shall you choose?” he asks. “When you are my wife?”

I begin to wonder if he has come only to torment me. I have not thought of this. Why on earth would I have thought of my wifely motto? “Oh, do you have a preference?” I ask him, my voice coldly uninterested. “For I have none.”

“My Lady Mother suggested ‘humble and penitent,’ ” he says.

Cecily snorts with laughter, turns it into a cough, and looks away, blushing. My mother and I exchange one horrified glance, but we both know we can say nothing.

“As you wish.” I manage to sound indifferent, and I am glad of this. If nothing else, I can pretend that I don’t care.

“Humble and penitent, then,” he says, quietly to himself, as if he is pleased, and now I am sure that he is laughing at us.

Next day my mother comes to me, smiling. “Now I understand why we were honored with a royal visit yesterday,” she says. “The speaker of the House of Parliament himself stepped down from his chair and begged the king, in the name of the whole house, to marry you. The commons and the lords told him that they must have the issue resolved. The people will not stand for him as king without you at his side. They put such a petition to him that he could not deny them. They promised me this, but I wasn’t sure they would dare to go through with it. Everyone is so afraid of him; but they want a York girl on the throne and the Cousins’ War concluded by a marriage of the cousins more than anything in the world. Nobody can feel certain that peace has come with Henry Tudor unless you’re on the throne too. They don’t see him as anything more than a lucky pretender. They told him they want him to be a king grafted onto the Plantagenets, this sturdy vine.”

“He can’t have liked that.”

“He was furious,” she says gleefully. “But there was nothing he could do. He has to have you as his wife.”

“Humble and penitent,” I remind her sourly.

“Humble and penitent it is,” my mother confirms cheerfully. She looks at my downcast face and laughs. “They’re just words,” she reminds me. “Words that he can force you to say now. But in return we make him marry you and we make you Queen of England, and then it really doesn’t matter what your motto is.”

WESTMINSTER PALACE, LONDON, DECEMBER 1485

The firewood boy toils up the stairs with another bath, and the Warwick children are banished to their rooms and told not to come downstairs, nor even to be seen at the windows.

“Why not?” Margaret asks me, slipping into my room behind the maids carrying an armful of warm linen and a bottle of rosewater for me to rinse my hair. “Does your lady mother think that Teddy is not quick enough to meet the king?” She flushes. “Is she ashamed of us?”

“Mother doesn’t want the king distracted by the sight of a York boy,” I say shortly. “It’s nothing to do with you, or Edward. Henry knows about you both, of course, you can be sure that his mother, in her careful audit of everything that England holds, has not forgotten you. She has made you her wards; but you’re safer out of sight.”

She pales. “You don’t think the king would take Teddy away?”

“No,” I say. “But there’s no need for them to dine together. It’s better if we don’t throw them together, surely. Besides, if Teddy tells Henry that he is expecting to be king, it would be awkward.”

She gives a little laugh. “I wish no one had ever told him that he was next in line for the throne,” she says. “He took it so much to heart.”

“He’s better out of the way until Henry is accustomed to everything,” I say. “And Teddy is a darling, but he can’t be trusted not to speak out.”

She glances around at the preparations for my bath, and the laying out of my new gown, brought from the City this very day by the dressmaker, in Tudor green with love knots at the shoulders. “Do you mind very much, Elizabeth?”

I shrug my shoulders, denying my own pain. “I am a princess of York,” I say. “I have to do this, I would always have had to marry someone to suit my father’s plans. I was betrothed in the cradle. I have no choice; but I never expected to have a choice—except once, and that feels like an enchanted time now, like a dream. When your time comes, you will have to marry where you are ordered too.”

“Does it make you sad?” she asks, she is such a dear serious girl.

I shake my head. “I feel nothing,” I tell her the truth. “That’s perhaps the worst thing. I don’t feel anything at all.”

Henry’s court arrives on time, handsomely dressed, with shy half-hidden smiles. Half of his court is composed of old friends of ours; most of us are related by marriage if not by blood. There are many things left unsaid as the lords come in and greet us, just as they used to do when we were the royal family, entertaining them here, at the palace.

My cousin John de la Pole, who Richard named as his heir before Bosworth, is there with his mother, my aunt Elizabeth. She and all her family are now loyal Tudors and greet us with careful smiles.

My other aunt, Katherine, now carries the name of Tudor, and walks on the arm of the king’s uncle Jasper; but she curtseys to my mother as low as she always did, and rises up to kiss her warmly.

My uncle Edward Woodville, my mother’s own brother, is among the Tudor court, an honored and trusted friend of the new king. He has been with Henry since he went into exile, and he fought in his army at Bosworth. He bows low over my mother’s hand, then kisses her on both cheeks as her brother, and I hear his whisper: “Good to see you back in your rightful place, Lizzie-Your-Grace!”

Mother has arranged an impressive feast with twenty-two courses, and after everyone has eaten and the plates and the trestle tables have been cleared away, my sisters Cecily and Anne dance before the court.

“Please, Princess Elizabeth, dance for us,” the king says briefly to me.

I look to my mother; we had agreed that I would not dance. Last time I danced in these rooms it was the Christmas feast and I was wearing a dress of silk as rich as Queen Anne’s own, made to the same pattern as the queen’s, as if to force a comparison between her and me—her junior by ten years; and her husband the king, Richard, could not take his eyes off me. The whole court knew that he was falling in love with me and that he would leave his old sick wife to be with me. I danced with my sisters, but he saw only me. I danced before hundreds of people, but only for him.

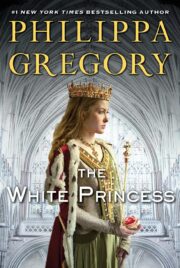

"The White Princess" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "The White Princess". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "The White Princess" друзьям в соцсетях.