“You are welcome to Coldharbour,” Lady Margaret says, and I think it is well named, for it is a most miserable and unfriendly haven. “And to our capital city,” she goes on, as if we girls had not been brought up here in London while she was stuck with a small and unimportant husband in the country, her son an exile and her house utterly defeated.

My mother looks around the rooms, and notes the second-rate cloth cushions on the plain window seat, and that the best tapestry has been replaced by an inferior copy. Lady Margaret Beaufort is a most careful housekeeper, not to say mean.

“Thank you,” I say.

“I have the arrangements for the wedding all in hand,” she says. “You can come to be fitted for your gown in the royal wardrobe next week. Your sisters and your mother also. I have decided that you will all attend.”

“I am to attend my own wedding?” I ask dryly, and see her flush with annoyance.

“All your family,” she corrects me.

My mother gives her blandest smile. “And what about the York prince?” she asks.

There is a sudden silence as if a snap frost has just iced the room. “The York prince?” Lady Margaret repeats slowly, and I can hear a tremor in her hard voice. She looks at my mother in dawning horror, as if something terrible is about to be revealed. “What d’you mean? What York prince? What are you saying? What are you saying now?”

My mother blankly meets her gaze. “You have not forgotten the York prince?”

Lady Margaret has blanched white as white. I can see her grip the arms of her chair, and her fingernails are bleached with the pressure of her panic-stricken grip. I glance at my mother; she is enjoying this, like a bear leader teasing the bear with a long-handled prod.

“What d’you mean?” Lady Margaret says and her voice is sharp with fear. “You cannot be suggesting . . .” She breaks off with a little gasp, almost as if she is afraid of what she might say next. “You cannot be saying now . . .”

One of her ladies steps forwards. “Your Grace, are you unwell?”

My mother observes this with detached interest, as an alchemist might observe a transformation. The upstart king’s mother is riven with terror at the very name of a York prince. My mother enjoys the sight for a moment, then she releases her from the spell. “I mean, Edward of Warwick, the son of George, Duke of Clarence,” she says mildly.

Lady Margaret gives a shuddering sigh. “Oh, the Warwick boy,” she says. “The Warwick boy. I had forgotten the Warwick boy.”

“Who else?” my mother asks sweetly. “Who did you think I meant? Who else could I mean?”

“I had not forgotten the Warwick children.” Lady Margaret grasps for her dignity. “I have ordered robes for them too. And gowns for your younger daughters also.”

“I am so pleased,” my mother says pleasantly. “And my daughter’s coronation?”

“Will follow later,” Lady Margaret says, trying to hide that she is gasping, still recovering from her shock, gulping for her words like a landed carp. “After the wedding. When I decide.”

One of her ladies steps forwards with a glass of malmsey and she takes a sip and then another. The color comes back to her cheeks with the sweet wine. “After their wedding they will travel to show themselves to the people. A coronation will follow after the birth of an heir.”

My mother nods, as if the matter is indifferent to her. “Of course, she’s a princess born,” she remarks, quietly pleased that being a princess born is far better than being a pretender king.

“I wish any child to be born at Winchester, at the heart of the old kingdom, Arthur’s kingdom,” Lady Margaret states, struggling to regain her authority. “My son is of the house of Arthur Pendragon.”

“Really?” my mother exclaims, all sweetness. “I thought he was from a Tudor bastard out of a Valois dowager princess. And that, a secret wedding, never proved? How does that trace back to King Arthur?”

Lady Margaret pales with rage, and I want to tug my mother’s sleeve to remind her not to torment this woman. She had Lady Margaret on the run at the mention of a York prince, but we are supplicants at this new court and there is no benefit in making its greatest woman angry.

“I don’t need to explain my son’s inheritance to you, whose own marriage and title was only restored by us, after you had been named as an adulteress,” Lady Margaret says bluntly. “I have told you of the arrangements for the wedding, I will not delay you further.”

My mother keeps her head up and smiles. “And I thank you,” she says regally. “So much.”

“My son will see Princess Elizabeth.” Lady Margaret nods to a page. “Take the princess to the king’s private rooms.”

I have no choice but to go through the interconnecting room, to the king’s chambers. It seems the two of them are never more than a doorway apart. He is seated at a table that I recognize at once as one used in this palace by my lover Richard, made for my father, King Edward. It is so strange to see Henry seated in my father’s chair, signing documents on Richard’s table, as if he were king himself—until I remember that he is indeed the king himself, his pale, worried face the image that will be stamped on the coins of England.

He is dictating to a clerk with a portable writing desk slung around his neck, a quill in one hand, another tucked behind his ear, but when Henry sees me, he gives me a broad welcoming smile, waves the man away, and the guards close the door on him and we are alone.

“Are they spitting like cats on a barn roof?” He chuckles. “There’s no great love lost between them, is there?”

I’m so relieved to have an ally that for a moment I nearly respond to his warmth, then I check myself. “Your mother is ordering everything, as usual,” I say coldly.

The merry smile is wiped from his face. He frowns at the least hint of criticism of her. “You have to understand that she has waited for this moment all her life.”

“I am sure we all know this. She does tell everyone.”

“I owe her everything,” he says frostily. “I can’t hear a word against her.”

I nod. “I know. She tells everyone that too.”

He rises from his chair and comes around the table towards me. “Elizabeth, you will be her daughter-in-law. You will learn to respect her and love and value her. You know, in all the years when your father was on the throne, my mother never gave up her vision.”

I grit my teeth. “I know,” I say. “Everybody knows. She tells everyone that as well.”

“You have to admire that in her.”

I cannot bring myself to say that I admire her. “My mother too is a woman of great tenacity,” I say carefully. Privately I think: But I don’t worship her like a baby, she doesn’t speak of nothing but me as if she had nothing in her life but one spoiled brat.

“I am sure they are filled with bile now, but before that they were friends and even allies,” he reminds me. “When we are married, they will join together. They’ll both have a grandson to love.”

He pauses as if he hopes I will say something about their grandson.

Unhelpfully, I stay silent.

“You are well, Elizabeth?”

“Yes,” I say shortly.

“And your course has not returned?”

I grit my teeth at having to discuss something so intimate with him. “No.”

“That’s good, that’s so good,” he says. “That’s the most important thing!” His pride and excitement would be such a pleasure from a loving husband, but from him it grates on me. I look at him in blank enmity and keep my silence.

“Now, Elizabeth, I just wanted to tell you that our wedding day is to be the feast of St. Margaret of Hungary. My mother has it all planned, you need do nothing.”

“Except walk up the aisle and consent,” I suggest. “I suppose even your mother will concede that I have to give my consent.”

He nods. “Consent, and look happy,” he adds. “England wants to see a joyful bride, and so do I. You will please me in this, Elizabeth. It is my wish.”

St. Margaret of Hungary was a princess like me, but she lived in a convent in such poverty that she fasted to death. The choice of her day for my wedding by my mother-in-law does not escape me. “Humble and penitent.” I remind him of the motto his mother chose for me. “Humble and penitent like St. Margaret.”

He has the grace to chuckle. “You can be as humble and penitent as you like.” He smiles and looks as if he would take my hand and kiss me. “You can’t exceed in humility for us, my sweetheart.”

WESTMINSTER PALACE, LONDON, 18 JANUARY 1486

I step out of my bed and she pulls my nightgown over my head and then offers me my undergarments, all new and trimmed with white silk embroidery on the white linen at the hem, then my red satin overgown slashed at the sleeves and opening at the front to show a black silk damask undergown. Fussing, she ties the laces under the arms while the two other maids-in-waiting tie those at the back. It is a little tighter than when it was first fitted on me. My breasts have grown fuller and my waist is thickening. I notice the changes, but nobody else does yet. I am losing the body that my lover adored, the girlish litheness that he used to wrap around his battle-hardened body. Instead I will be the shape that my husband’s mother wants: a rounded fertile pear of a woman, a vessel for Tudor seed, a pot.

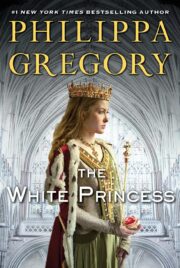

"The White Princess" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "The White Princess". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "The White Princess" друзьям в соцсетях.