“Edward is a child,” I say quickly, breathless with relief that at least he has no news of a York prince, no knowledge of his whereabouts, no revealing detail of his looks, his education, his claim. “And completely loyal to you, as is my mother now. We gave you our word that Teddy would never challenge you. We promised him to you. He has sworn loyalty. Of all of us, above us all, you can trust him.”

“I hope so,” he says. “I hope so.” He looks drained by his fears. “But even so—I have to do everything! I have to hold this country to peace, to secure the borders. I am trying to do a great thing here, Elizabeth. I am trying to do what your father did, to establish a new royal family, to set its stamp on the country, to lead the country to peace. Your father could never get an established peace with Scotland though he tried, just as I am trying. If your mother would go to Scotland for us, and hold them to an alliance, she would do you a service, and me a service, and her grandson would be in debt to her all his life for his safe inheritance of England. Think of that! Giving our son his kingdom with borders at peace! And she could do it!”

“I have to have her with me!” It is a wail like that of a child. “You wouldn’t send your own mother away. She has to be with you all the time! You keep her close enough!”

“She serves our house,” he says. “I am asking your mother to serve our house too. And she is a beautiful woman still, and she knows how to be queen. If she were Queen of Scotland, we would all be safer.”

He stands. He puts his hands on either side of my thickening waist and looks down into my troubled face. “Ah, Elizabeth, I would do anything for you,” he says gently. “Don’t be troubled, not when you are carrying our son. Please don’t cry. It’s bad for you. It’s bad for the baby. Please—don’t cry.”

“We don’t even know if it is a son,” I say resentfully. “You say it all the time, but it doesn’t make it so.”

He smiles. “Of course it is a boy. How could a beautiful girl like you make anything for me but a handsome firstborn son?”

“I have to have my mother with me,” I stipulate. I look up into his face and catch a glimpse of an emotion I never expected to see. His hazel eyes are warm, his mouth is tender. He looks like a man in love.

“I need her in Scotland,” he says, but his voice is soft.

“I cannot give birth without her here. She has to be with me. What if something goes wrong?”

It is my greatest card, a trump.

He hesitates. “If she is with you for the birth of our boy?”

Sulkily I nod my head. “She must be with me till he is christened. I will be happy in my confinement only if she is with me.”

He drops a kiss on the top of my head. “Ah, then I promise,” he says. “You have my word. You bend me to your will like the enchantress you are. And she can go to Scotland after the birth of your baby.”

WESTMINSTER PALACE, LONDON, MARCH 1486

She solves the problem by drowning him in jewels. He never goes out without a precious brooch in his hat, or a priceless pearl at his throat. He never rides without gloves encrusted with diamonds, or a saddle with stirrups of gold. She bedecks him in ermine as if she were decorating a relic for an Easter procession; and still he looks like a young man stretched beyond his abilities, living beyond his means, ambitious and anxious all at once, his face pale against purple velvet.

“I wish you could come with me,” he says miserably one afternoon when we are in the stable yards of Westminster Palace, choosing the horses he will ride.

I am so surprised that I look twice at him to see if he is mocking me.

“You think I am joking? No. I really wish you could come with me. You’ve done this sort of thing all your life. Everyone says that you used to open the dancing at your father’s court and talk to the ambassadors. And you have been all round the country, haven’t you? You know most of the cities and towns?”

I nod. Both my father and Richard were well loved, especially in the northern counties. We rode out of London to visit the other cities of England every summer, and were greeted as if we were angels descending from heaven. Most of the great houses of every county celebrated our arrival with glorious pageants and feasts; most cities gave us purses of gold. I couldn’t count how many mayors and councillors and sheriffs have kissed my hand from when I was a little girl on my mother’s lap to when I could give a thank-you speech in faultless Latin on my own.

“I have to show myself everywhere,” he says apprehensively. “I have to inspire loyalty. I have to convince people that I will bring them peace and wealth. And I have to do all this with nothing more than a smile and wave as I ride by?”

I can’t help but laugh. “It does sound impossible,” I say. “But it’s not so bad. Remember, everyone on the roadside has come out just to see you. They want to see a great king, that’s the show they’ve turned out for. They’re expecting a smile and a wave. They are hoping for a happy lord. You just have to look the part and everyone is reassured. And remember that they have nothing else to look at—really, Henry, when you know England a little better you will see that almost nothing ever happens here. The crops fail, it rains too much in spring, it’s too dry in summer. Offer the people a well-dressed and smiling young king and you will be the most wonderful thing they have seen in many years. These are poor people without entertainment. You will be the greatest show they have ever seen—especially since your mother is exhibiting you like a holy icon, wrapped in velvet and studded with jewels.”

“It all takes so long,” he grumbles. “We have to stop at practically every house and castle on the road, to hear a loyal address.”

“Father used to say that while the speeches were going on he looked over their heads at the numbers in the crowd and worked out what they could afford to lend him,” I volunteer. “He never listened to a word that anyone was saying, he counted the cows in the fields and the servants in the yard.”

Henry is immediately interested. “Loans?”

“He always thought it was better to go straight to the people than go to Parliament for taxes, where they would argue with him as to how the country should be run, or whether he might go to war. He used to borrow from everyone that he visited. And the more passionate the speech and the more exaggerated the praise, the greater the sum of money he asked for, after dinner.”

Henry laughs and puts an arm around my broad waist and draws me to him, in the stable yard, before everyone. “And did they always lend him money?”

“Almost always,” I say. I don’t pull away but neither do I lean towards him. I let him hold me, as he has a right to do, as a husband can hold his wife. And I feel the warmth of his hand as he spreads his fingers over my belly. It’s comforting.

“I’ll do that then,” he says. “Because your father was right, it’s an expensive business trying to rule this country. Everything that I am granted in taxes from Parliament I have to give away in gifts to keep the loyalty of the lords.”

“Oh, don’t they serve you for love?” I ask nastily. I cannot stop my sharp tongue.

At once, he releases me. “I think we both know that they don’t.” He pauses. “But I doubt they loved your father that much, either.”

WESTMINSTER PALACE, LONDON, APRIL 1486

Lady Margaret is so impressed with her own rule making, by the quality of her advice, that she starts to write down the orders that she gives out in my household, so that everything will always be done exactly as she has devised, for years in the future, even after her death. I imagine her, beyond the grave, still ruling the world as my daughter and my granddaughters consult the great book of the royal household, and learn that they are not to eat fresh fruit, nor to sit too close to the fire. They are to avoid overheating and not to take a chill.

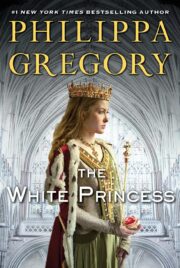

"The White Princess" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "The White Princess". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "The White Princess" друзьям в соцсетях.