“What’s happening?” I ask. “What’s happening down there?”

“The people are rising against Henry Tudor,” my mother says calmly.

“What?”

“They’re gathering outside the palace, mustering, in their hundreds.”

I feel the baby move uneasily in my belly. I sit down, take a gasping breath. “What should we do?”

“Stay here,” my mother says steadily. “Until we can see our way.”

“What way?” I ask impatiently. “Where will we be safe?”

She looks back at my white face and smiles. “Be calm, my dear. I mean, we stay here till we know who’s won.”

“Do we even know who’s fighting?”

She nods. “It is the English people who still love the House of York, against the new king,” she says. “We’re safe either way. If Lovell wins in Yorkshire, if the Stafford brothers win their battles in Worcestershire, if these London citizens take the Tower and then set siege here—then we come out.”

“And do what?” I whisper. I am torn between a growing excitement and an absolute dread.

“Retake the throne,” my mother says easily. “Henry Tudor is in a desperate fight to hold his kingdom, only nine months after winning it.”

“Retake the throne!” My voice is a squeak of terror.

My mother shrugs. “It’s not lost to us until England is at peace and united behind Henry Tudor. This could be just another battle in the Cousins’ War. Henry could be just an episode.”

“The cousins are all gone!” I exclaim. “The brothers who were of the houses of Lancaster and York are all gone!”

She smiles. “Henry Tudor is a cousin of the House of Beaufort,” she reminds me. “You are of the House of York. You have a cousin in John de la Pole, your aunt Elizabeth’s son. You have a cousin in Edward Earl of Warwick, your uncle George’s son. There is another generation of cousins—the question is only whether they want to go to war against the one who is now on the throne.”

“He’s ordained king! And my husband!” I raise my voice, but nothing perturbs her.

She shrugs. “So you win either way.”

“D’you see what they’re carrying?” Maggie squeaks with excitement. “Do you see the flag?”

I rise from my chair and look over her head. “I can’t see it from here.”

“It’s my flag,” she says, her voice trembling with joy. “It’s the ragged staff of Warwick. And they’re calling my name. They’re calling À Warwick! À Warwick! They’re calling for Teddy.”

I look over her bobbing head to my mother. “They’re calling for Edward, the heir of York,” I say quietly. “They’re calling for a York boy.”

“Yes,” she says equably. “Of course they are.”

We wait for news. It is hard for me to bear the wait, knowing that my friends and my family and my house are up in arms against my own husband. But it is harder on My Lady the King’s Mother, who seems to have given up sleeping altogether but is every night on her knees before the little altar in her privy chamber, and all day in the chapel. She grows thin and gray with worry; the thought of her only son far away in this faithless country, with no protection but his uncle’s army, makes her ill with fear. She accuses his friends of failing him, his supporters of fading away from him. She lists their names in her prayers to God, one after another, the men who flocked to the victor but will abandon a failure. She goes without food, fasting to draw down the blessing of God; but we can all see that she is sick with the growing fear that despite it all, her son is not blessed by God, that for some unknown reason, God has turned against the Tudors. He has given them the throne of England but not the power to hold it.

There are skirmishes between the London bands and the Tudor forces in the little villages in the countryside outside Westminster, as if every crossroads is calling out À Warwick! At Highbury there is a pitched battle with the rebels armed with stones, rakes, and scythes against the heavily armed royal guard. There are stories of Henry’s soldiers throwing down the Tudor standard and running to join the rebels. There are whispers that the great merchants of London and even the City Fathers are supporting the mobs that roam the streets shouting for the return of the House of York.

Lady Margaret orders the shutters closed over all the windows that face the streets, so that we cannot see the running battles that are being fought below the very walls of the palace. Then she orders the shutters bolted on the other windows too so that we can’t hear the mob shouting support for York, demanding that Edward of Warwick, my little cousin Teddy, come out and wave to them.

We keep him from the windows of the schoolroom, we forbid the servants to gossip, but still he knows that the people of England are calling for him to be king.

“Henry is the king,” he volunteers to me as I listen to him read a story in the schoolroom.

“Henry is the king,” I confirm.

Maggie glances over at the two of us, frowning with worry.

“So they shouldn’t shout for me,” he says. He seems quite resigned.

“No, they should not,” I say. “They will soon stop shouting.”

“But they don’t want a Tudor king.”

“Now, Teddy,” Margaret interrupts. “You know you must say nothing.”

I put my hand over his. “It doesn’t matter what they want,” I tell him. “Henry won the battle and was crowned Henry VII. He is King of England, whatever anyone says. And we would all be very, very wrong if we forgot that he is King of England.”

He looks at me with his bright honest face. “I won’t do that,” he promises me. “I don’t forget things. I know he’s king. You’d better tell the boys in the streets.”

I don’t tell the boys in the streets. Lady Margaret does not allow anyone out of the great gates until slowly the excitement dies down. The walls of Westminster Palace are not breached, the thick gates cannot be forced. The ragged mobs are kept off, they are driven away, they flee the city or they go back into sullen hiding. The streets of London become quiet again, and we open the shutters at the windows and the heavy gates of the palace as if we were confident rulers and can welcome our people. But I notice that the mood in the capital is surly and every visit to market provokes a quarrel between the court servants and the traders. We keep double sentries on the walls and we still have no news from the North. We simply have no idea whether Henry has met the rebels in a battle, nor who has won.

Finally at the end of May—when the court should be planning the sports of the summer, walking by the river, practicing jousting, rehearsing plays, making music, and courting—a letter comes from Henry for My Lady, with a note for me, and an open letter to the Parliament, carried by my uncle Edward Woodville with a smartly turned out party of yeomen of the guard, as if to show that the Tudor servants can wear their livery in safety all the way down the Great North Road from York to London.

“What does the king say?” my mother asks me.

“The rebellion is over,” I say, reading rapidly. “He says that Jasper Tudor pursued the rebels far into the North and then came back. Francis Lovell has escaped, but the Stafford brothers have fled back into sanctuary. He’s pulled them out of sanctuary.” I pause and look at my mother over the top of the paper. “He’s broken sanctuary,” I remark. “He’s broken the law of the Church. He says he’ll execute them.”

I hand her the letter, surprised at my own sense of relief. Of course I want the restoration of my house and the defeat of Richard’s enemy—sometimes I feel a thrill of violent desire at the sudden vivid image of Henry falling from his horse and fighting for his life on the ground in the middle of a cavalry charge as the hooves thunder by his head—and yet, this letter brings me the good news that my husband has survived. I am carrying a Tudor in my belly. Despite myself, I can’t wish Henry Tudor dead, thrown naked and bleeding across the back of his limping horse. I married him, I gave him my word, he is the father of my unborn child. I might have buried my heart in an unmarked grave, but I have promised my loyalty to the king. I was a York princess, but I am a Tudor wife. My future must be with Henry. “It’s over,” I repeat. “Thank God it’s over.”

“It’s not over at all,” my mother quietly disagrees. “It’s just beginning.”

PALACE OF SHEEN, RICHMOND, SUMMER 1486

My Lady the King’s Mother makes representation to the Holy Father through her cat’s-paw John Morton, and the helpful word comes from Rome that the laws on sanctuary are to be changed to suit the Tudors. Traitors may not go into hiding behind the walls of the Church anymore. God is to be on the side of the king and to enforce the king’s justice. My Lady wants her son to rule England inside sanctuary, right up to the altar, perhaps all the way to heaven, and the Pope is persuaded to her view. Nowhere on earth can be safe from Henry’s yeomen of the guard. No door, not even one on holy ground, can be closed in their hard faces.

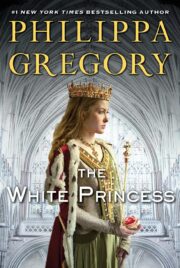

"The White Princess" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "The White Princess". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "The White Princess" друзьям в соцсетях.