The might of English law is to favor the Tudors too. The judges obey the new king’s commands, trying men who followed the Staffords or Francis Lovell, pardoning some, punishing others, according to their instructions from Henry. In my father’s England the judges were supposed to make up their own minds, and a jury was supposed to be free of any influence but the truth. But now the judges wait to hear the preferences of the king before reaching their sentences. The statements of the accused men, even their pleas of guilt, are of less importance than what the king says they have done. Juries are not even consulted, not even sworn in. Henry, who stayed away from the fighting, rules at long distance through his spineless judges, and commands life and death.

Not until August does the king come home and at once he moves the court away from the city that threatened him, out of town to the beautiful newly restored Palace of Sheen by the river. My uncle Edward comes with him, and my cousin John de la Pole, riding easily in the royal train, smiling at comrades who do not wholly trust them, greeting my mother as a kinswoman in public and never, never talking with her in private, as if they have to demonstrate every day that there are no whispered secrets among the Yorks, that we are all reliably loyal to the House of Tudor.

There are many who are quick to say that the king does not dare to live in London, that he is afraid of the twisting streets and the dark ways of the city, of the sinuous secrets of the river and those who silently travel on it. There are many who say he is not sure of the loyalty of his own capital city and that he does not trust his safety within its walls. The trained bands of the city keep their own weapons to hand, and the apprentices are always ready to spring up and riot. If a king is well loved in London, then he has a wall of protection around him, a loyal army always at his doors guarding him. But a king with uncertain popularity is under threat every moment of the day, anything—hot weather, a play that goes wrong, an accident at a joust, the arrest of a popular youth—can trigger a riot which might unseat him.

Henry insists that we must move to Sheen as he loves the countryside in summer and exclaims at the beauty of the palace and the richness of the park. He congratulates me on the size of my belly and insists that I sit down all the time. When we walk together into dinner he demands that I lean heavily on his arm, as if my feet are likely to fail underneath me. He is tender and kind to me, and I am surprised to find that it is a relief to have him home. His mother’s anguished vigilance is soothed by the sight of him, the constant uneasiness of being a new court in an uncertain country is eased, and the court feels more normal with Henry riding out to hunt every morning and coming home boasting of fresh venison and game every night. His looks have improved during his long summertime journey around England, his skin warmed by the sunshine, and his face more relaxed and smiling. He was afraid of the North of England before he went there, but once the worst of his fears did indeed happen, and he survived it, he felt victorious once again.

He comes to my room every evening, sometimes bringing a syllabub straight from the kitchen for me to drink while it is warm, as if we did not have a hundred servants to do my bidding. I laugh at him, carrying the little jug and the cup, neat as a groom of the servery.

“Well, you’re used to having people do things for you,” he says. “You were raised in a royal household with dozens of servants waiting around the room for something to do. But in Brittany I had to serve myself. Sometimes we had no house servants. Actually, sometimes we had no house, we were all but homeless.”

I go to my chair by the fire, but that is not good enough for the mother of the next prince.

“Sit on the bed, sit on the bed, put your feet up,” he urges, and helps me up, taking my shoes and pressing the cup in my hands. Like a pair of little merchants snug in their town house, we eat our supper alone together. Henry puts a poker into the heart of the fire and when it is hot, plunges it into a jug of small ale. The drink seethes and he pours it out while it is steaming and tastes it.

“I can tell you my heart turned to stone at York,” he says to me frankly. “Freezing cold wind and a rain that could cut through you, and the faces of the women like stone itself. They looked at me as if I had personally murdered their only son. You know what they’re like—they love Richard as dearly as if he rode out only yesterday. Why do they do that? Why do they cling to him still?”

I bury my face in the syllabub cup so that he cannot see my swift betraying flinch of grief.

“He had that York gift, didn’t he?” he presses me. “Of making people love him? Like your father King Edward did? Like you have? It’s a blessing, there’s no real sense to it. It’s just that some men have a charm, don’t they? And then people follow them? People just follow them?”

I shrug. I can’t trust my voice to speak of why everyone loved Richard, of the friends who would have laid down their lives for him and who, even now after his death, still fight his enemies for love of his memory. The common soldiers who will still brawl in taverns when someone says that he was a usurper. The fishwives who will draw a knife on anyone who says he was hunchbacked or weak.

“I don’t have it, do I?” Henry asks me bluntly. “Whatever it is—a gift or a trick or a talent. I don’t have it. Everywhere we went, I smiled and waved and did all that I could, all that I should. I acted the part of a king sure of his throne even though I sometimes felt like a penniless pretender with no one who believes in me but a besotted mother and a doting uncle, a pawn for the big players who are the kings of Europe. I’ve never been someone deeply beloved by a city, I’ve never had an army roar my name. I’m not a man who is followed for love.”

“You won the battle,” I say dryly. “You had enough men follow you on the day. That’s all that matters, that one day. As you tell everyone: you’re king. You’re king by right of conquest.”

“I won with hired troops, paid by the King of France. I won with an army loaned to me from Brittany. One half of them were mercenaries and the other half were murderous criminals pulled out of the jails. I didn’t have men that served me for love. I’m not beloved,” he says quietly. “I don’t think I ever will be. I don’t have the knack of it.”

I lower the cup and for a moment our eyes meet. In that one accidental exchange I can see that he is thinking that he is not even loved by his own wife. He is—simply—loveless. He spent his youth waiting for the throne of England, he risked his life fighting for the throne of England, and now he finds it is a hollow crown indeed; there is no heart at the center. It is empty.

I can think of nothing to fill the awkward silence. “You have adherents,” I offer.

He gives a short bitter laugh. “Oh yes, I have bought some: the Courtenays and the Howards. And I have the friends that my mother has made for me. I can count on a few friends from the old days, my uncle, the Earl of Oxford. I can trust the Stanleys, and my mother’s kin.” He pauses. “It’s an odd question for a husband to ask his wife, but I could think of nothing else when they told me that Lovell had come against me. I know that he was Richard’s friend. I see that Francis Lovell loves Richard so much that he fights on even when Richard is dead. It made me wonder: can I count on you?”

“Why would you even ask?”

“Because they all tell me that you loved Richard too. And I know you well enough now to be sure that you were not guided by ambition to be his queen, you were driven by love. So that’s why I ask you. Do you love him still? Like Lord Lovell? Like the women of York? Do you love him despite his death? Like York does, like Lord Lovell does? Or can I count on you?”

I shift slightly as if I am uncomfortable on the soft bed, sipping my drink. I gesture to my belly. “As you say, I am your wife. You can count on that. I am about to have your child. You can count on that.”

He nods. “We both know how that came about. It was done to breed a child; it was not an act of love. You would have refused me if you could have done, and every night you turned your face away. But I have been wondering, while I was gone, facing such unfriendliness, facing a rebellion, whether loyalty might grow, whether trust can grow between us?”

He does not even mention love.

I glance away. I cannot meet his steady gaze, and I cannot answer his question. “All this I have already promised,” I say inadequately. “I said my marriage vows.”

He hears the refusal in my voice. Gently he leans over and takes the empty cup from me. “I’ll leave it at that, then,” he says, and goes from my room.

ST. SWITHIN’S PRIORY, WINCHESTER, SEPTEMBER 1486

If My Lady the King’s Mother was able publicly to declare when the baby was conceived—a full month before our wedding—she would have had me locked up four weeks ago. She has already written in her Royal Book that a queen must be confined a full six weeks before the expected date of a birth. She must give a farewell dinner and the court must escort her to the door of the confinement chamber. She must go in, and not come out again (God willing, writes the pious lady at this point) until six weeks after the birth of a healthy child, when the babe is brought out to be christened, and she emerges to be churched and can take her place at court once more. A stay in silence and darkness of a long three months’ duration. I read this, in her elegant black-ink handwriting, and I study her opinions about the quality of the tapestries on the walls and the hangings on the bed, and I think that only a barren woman would compose such a regime.

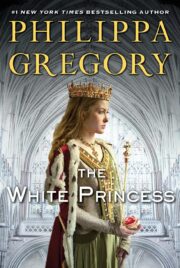

"The White Princess" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "The White Princess". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "The White Princess" друзьям в соцсетях.