My Lady the King’s Mother had only one child, her precious son Henry, and she has been barren since his birth. I think that if there were any chance that she would be put away from the world for three months every year, the orders on confinement would be very different. These rules are not to secure my privacy and rest, they are to keep me out of the way of the court so that she can take my place for three glorious long months every time her son gets me with child. It is as simple as that.

But this time, wonderfully, the joke is on her, for since we have, all three of us, loudly and publicly declared that the baby is a honeymoon baby, the blessedly quick result of a January wedding, it should be born in the middle of October, and so by her own rules, I don’t have to go into confinement until now, the first week in September. If she had put me into darkness at seven and a half months, I should have missed all of August, but I have been free—big-bellied but gloriously free—and I have laughed up my sleeve for a month as I have seen this deception eat away at her.

Now I expect to spend only a week or so before the birth in this gloomy twilight, banned from the outside world, seeing no man but a priest through a shaded screen. Then I will have six long weeks of isolation after the birth. In my absence I know that My Lady will relish ruling the court, receiving congratulations on the birth of her grandchild, supervising the christening and ordering the feast, while I am locked in my rooms and no man—not even my husband, her son—can see me.

My maid is bringing a green gown from the wardrobe for my official farewell. I wave it away, I am so very tired of wearing Tudor green, when the door bursts open and Maggie comes running into the room and flings herself on her knees before me. “Elizabeth, I mean Your Grace! Elizabeth! Oh, Elizabeth, save Teddy!”

The baby seems to jump in alarm in my belly as I leap off the bed and catch at the hangings as the room swings dizzily around me. “Teddy?”

“They’re taking him! They’re taking him away!”

“Careful!” my sister Cecily warns at once, hurrying to my side and steadying me on my feet. I don’t even hear her.

“Taking him where?”

“To the Tower!” Maggie cries out. “To the Tower! Oh! Come quick and stop them. Please!”

“Go to the king,” I throw at Cecily over my shoulder as I quickly head to the door. “Give him my compliments and ask if I may come to see him at once.” I grab my cousin Maggie’s arm and say, “Come on, I’ll come with you and stop them.”

Hurriedly, I go barefoot down the long stone corridors, the herbs brushed by my trailing nightgown, then Maggie sprints ahead of me up the circular stone staircase to the nursery floor, where she and Edward and my little sisters Catherine and Bridget have their rooms with their tutors and their maids. But then I see her fall back, and I hear the noise of half a dozen heavy boots coming down the stairs. “You can’t take him!” I hear her say. “I have the queen here! You can’t take him.”

As they come down the curve of the stair I see first the booted feet of the leading man, then his deep scarlet leggings, and then his bright scarlet tunic trimmed and quartered with gold lace: the uniform of the yeomen of the guard, Henry’s newly created personal troop. Behind him comes another, and another; they have sent a corps of ten men to collect a pale and shaking little boy of eleven. Edward is so afraid that the last man is holding him under the armpits so that he does not fall down the stairs; his feet are dangling, his skinny legs kicking as they half-carry him to where I am standing at the foot of the stairs. He looks like a doll with brown tousled curls and wide frightened eyes.

“Maggie!” he cries, on seeing his sister. “Maggie, tell them to put me down!”

I step forwards. “I am Elizabeth of York,” I say to the man at the front. “Wife of the king. This is my cousin, the Earl of Warwick. You shouldn’t even touch him. What d’you think you are doing?”

“Elizabeth, tell them to put me down!” Teddy insists. “Put me down! Put me down!”

“Release him,” I say to the man who is holding him.

Abruptly the guard drops him, but as soon as Teddy’s feet touch the floor he collapses into a heap, weeping with frustration. Maggie is down beside him in a moment, hugging him to her shoulder, smoothing his hair, stroking his cheeks, petting him into quietness. He pulls back from her shoulder to look earnestly into her eyes. “They lifted me from my desk in the schoolroom,” he exclaims in his piping little-boy voice. He is shocked that anyone should touch him without his permission; he has been an earl all his life, he has only ever been gently raised and carefully served. For a moment, looking at his tearstained face I think of the two boys in the Tower who were lifted from their beds, and there was no one there to stop the men who came for them.

“Orders of the king,” the commander of the yeomen says briefly to me. “He won’t be harmed.”

“There has been a mistake. He has to stay here, with us, his family,” I reply. “Wait here, while I go to speak to His Grace the King, my husband.”

“My orders are clear,” the man starts to argue, as the door opens and Henry appears in the doorway, dressed for riding, a whip in one hand, his expensive leather gloves in the other. My sister Cecily peeps around him to see Maggie and me, with young Edward struggling to his feet.

“What’s this?” Henry demands, without a word of greeting.

“There’s been some mistake,” I say. I am so relieved to see him that I forget to curtsey, but go quickly towards him and take his warm hand. “The yeomen thought they had to take Edward to the Tower.”

“They do,” Henry says shortly.

I am startled at his tone. “But my lord . . .”

He nods at the yeoman. “Carry on. Take the boy.”

Maggie gives a little yelp of dismay and flings her arm around Teddy’s neck.

“My lord,” I say urgently. “Edward is my cousin. He has done nothing. He is studying in the nursery here with my sisters and his sister. He loves you as his king.”

“I do,” Teddy says clearly. “I have promised. They told me to say that I promise, and so I did.”

The yeomen have closed up around him again, but they are waiting for Henry to speak.

“Please,” I say. “Please let Teddy stay here with all of us. You know he would never harm anyone. Certainly not you.”

Henry takes me gently by the shoulder and leads me away from the rest of them. “You should be resting,” he says. “You should not have been disturbed by this. You should not be upset. You should be going into confinement. This was all supposed to happen after you had gone in.”

“I’m very near to my time,” I whisper urgently to him. “As you know. Very near. Your mother says that I must stay calm, it might hurt the baby if I’m not calm. But I won’t be able to be calm if Teddy is taken from us. Please let him stay with us. I am feeling unhappy.” I take a swift glance at his piercing brown eyes which are scanning my face. “Very unhappy, Henry. I feel distressed. I am troubled. Please tell me that it’ll be all right.”

“Go and lie down in your room,” he says. “I’ll sort this out. You shouldn’t have been troubled. You shouldn’t have been told.”

“I’ll go to my room,” I promise. “But I must have your word that Teddy stays with us. I’ll go, as soon as I know that Teddy can stay here.”

With a sudden sense of dread I see My Lady the King’s Mother step into the room. “I will take you back to your bedchamber,” she offers. Some of her ladies-in-waiting come in behind her. “Come.”

I hesitate. “Go on,” Henry says. “Go with my mother. I’ll settle things here and then come and see you.”

“But Teddy stays with us,” I stipulate.

Henry hesitates and as he does so, his mother steps quietly around me to stand behind me. She wraps me in her arms, holding me close. For a moment I think it is a loving embrace, then I feel the strength in her grip. Two of her ladies-in-waiting come up on either side of her and hold my arms. I am captured, to my absolute amazement, I am held. One of the ladies scoops up Maggie and two of them hold her as the yeomen of the guard lift Teddy bodily and carry him from the room.

“No!” I scream.

Maggie is struggling and kicking, lashing out to get to her brother.

“No! You can’t take Teddy, he’s done nothing! Not the Tower! Not Teddy!”

Henry throws one horrified glance at me, held by his mother, struggling to be free, and then turns and goes out of the room, following his guard.

“Henry!” I scream after him.

My Lady the King’s Mother puts a hard hand over my mouth to silence me and we hear the tramp of the guards’ feet going down the gallery and then down the stairs at the end. Then we hear the outer door bang. When there is silence, My Lady takes her hand from my mouth.

“How dare you! How dare you hold me? Let me go!”

“I will take you to your room,” she says steadily. “You must not be upset.”

“I am upset!” I scream at her. “I am upset! Teddy can’t go to the Tower.”

She does not even answer me but nods at her ladies to follow her and they guide me firmly from the room. Behind me, Maggie has collapsed into tears, and the women who were holding her lower her gently to the ground and wipe her face and whisper to her that everything will be well. My sister Cecily is aghast at the sudden, smooth violence of the scene. I want her to go and fetch our mother, but she is stupid with shock, staring, from me to My Lady, as if the king’s mother had grown fangs and wings and was holding me prisoner.

“Come,” My Lady says. “You should lie down.”

She leads the way and the women release me to follow her. I walk behind her, struggling to regain my temper. “My Lady, I must ask you to intercede for my little cousin Edward,” I say to her stiff back, her white wimple, her rigid shoulders. “I beg you to speak to your son and ask him to release Teddy. You know Teddy is a young boy innocent of any bad thought. You made him your ward, any accusation of him is a reflection on you.”

She says nothing, leading the way past the closed doors. I am following her blindly, searching for words that will make her stop, turn, agree, as she opens the double doors of a darkened room.

“He is your ward,” I say. “He should be in your keeping.”

She does not answer me. “Here. Come in. Rest.”

I step inside. “Lady Margaret, I beg of you . . .” I start, and then I see that her ladies have followed us into the shadowy room and one of them has turned the key in the lock of the door and given it quietly to My Lady.

“What are you doing?” I demand.

“This is your confinement chamber,” she answers.

Now, for the first time, I realize where she has led me. It is a long, beautiful room with tall arched windows, blocked with tapestries so that no light creeps in. One of the ladies-in-waiting is lighting the candles, their yellow flickering light illuminating the bare stone walls and the high arched ceiling. The far end of the room is sheltered by a screen, and I can see an altar and the candles burning before a monstrance, a crucifix, a picture of Our Lady. Before the screen are prayer stools and before them the fireplace and a grand chair and lesser stools arranged in a conversational circle. Chillingly, I see that my sewing is on the table by the grand chair, and the book that I was reading before I lay down for my nap has been taken from my bedchamber and is open beside it.

Next is a dining table and six chairs, wine and water in beautiful Venetian glass jugs on the table, gold plates ready for serving dinner, a box with pastries in case of hunger.

Nearest to us is a grand bed, with thick oak posts and rich curtains and tester. On an impulse I open the chest at the foot of the bed and there, neatly folded and interspersed with dried lavender flowers, are my favorite gowns and my best linen, ready for me to wear when they fit me again. There is a day bed, next to the chest, and a beautifully carved and engraved royal cradle, all ready with linen beside the bed.

“What is this?” I ask as if I don’t know. “What is this? What is this?”

“You are in confinement,” Lady Margaret says patiently, as if speaking to an idiot. “For your health and for the health of your child.”

“What about Teddy?”

“He has been taken to the Tower for his own safety. He was in danger here. He needs to be carefully guarded. But I will speak to the king about your cousin. I will tell you what he says. Without question, he will judge rightly.”

“I want to see the king now!”

She pauses. “Now, daughter, you know that you cannot see him, or any man, until you come out of confinement,” she says reasonably. “But I will give him any message or take him any letter you wish to write.”

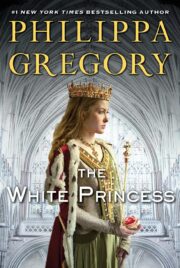

"The White Princess" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "The White Princess". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "The White Princess" друзьям в соцсетях.