As we watch, he opens his mouth in a little yawn, compresses his tiny face, flaps his arms like a fledgling, and then wails to be fed. “My lord prince,” my mother says lovingly. “Impatient as a king. Here, I’ll give him to Meg.”

The wet nurse is ready for him, but he cries and fusses and cannot latch on.

“Should I feed him?” I ask eagerly. “Would he feed from me?”

The rockers, the wet nurse, even my mother, all shake their heads in absolute unison.

“No,” my mother says regretfully. “That’s the price you pay for being a great lady, a queen. You can’t nurse your own child. You have won him a golden spoon and the best food in the world for all his life, but he cannot have his mother’s milk. You can’t mother him as you might wish. You’re not a poor woman. You’re not free. You have to be back in the king’s bed as soon as you are able and give us another baby boy.”

Jealously, I watch as he nuzzles at another woman’s breast and finally starts to feed. The wet nurse gives me a reassuring smile. “He’ll do well on my milk,” she says quietly. “You need not fear for him.”

“How many boys do you need?” I demand irritably of my mother. “Before I can stop bearing them? Before I can feed one?”

My mother, who gave birth to three royal boys and has none of them today, shrugs her shoulders. “It’s a dangerous world,” is all she says.

The door opens without a knock and My Lady comes in. “Is he ready?” she asks without preamble.

“He’s feeding.” My mother rises to her feet. “He’ll be ready in a little while. Are you waiting for him?”

Lady Margaret inhales the sweet, clean smell of the room as if she is greedy for him. “It’s all ready,” she says. “I have ordered it to the last detail. They are lining up in the Great Hall, waiting only for the Earl of Oxford.” She looks around for Anne and Cecily, and nods approval at their ornate gowns. “You are honored,” she says. “I have allowed you two the most important positions: carrying the chrism, carrying the prince himself.” She turns to my mother. “And you, named as godmother to a prince, a Tudor prince! Nobody can say that we have not united the families. Nobody can declare for York anymore. We are all one. I have planned today to prove it.” She looks at the wet nurse as if she would snatch the baby from her. “Will he be ready soon?”

My mother hides a smile. It is very clear that My Lady may know everything about christening princes but nothing about babies. “He will be as long as he needs,” she rules. “Probably less than an hour.”

“And what is he to wear?”

My mother gestures to the beautiful gown that she has made for him from the finest French lace. It has a train that sweeps to the floor and a tiny pleated ruff. Only she and I know that she cut it too large, so that this baby who was a full nine months in the womb will look small, as if he had come a month before his time.

“It will be the greatest ceremony in this reign,” My Lady the King’s Mother says. “Everyone is here. Everyone will see the future King of England, my grandson.”

They wait and wait. It makes no difference to me, bidden to rest in bed whatever takes place. The tradition is that the mother shall not be present at the christening and My Lady is not likely to break such a custom in order to bring me forwards. Besides, I am exhausted, torn between a sort of wild joy and a desperate fatigue. The baby feeds, they change his clout, they put him into my arms, and we sleep together, my arms around his tiny form, my nose sniffing his soft head.

The Earl of Oxford, hastily summoned, rides to Winchester as fast as he can, but My Lady the King’s Mother rules that they have waited long enough and will go on without him. They take the baby and off they all go. My mother is godmother, my sister Cecily carries the baby, my cousin Margaret leads the procession of women, Lord Neville goes before them carrying a lit taper. Thomas, Lord Stanley, and his son, and his brother Sir William—all heroes of Bosworth who stood on the hillside and watched Richard their king lead a charge without them, and then rode him down to his death—all walk together behind my son, as if he can count on their support, as if their word is worth anything, and present him to the altar.

While they are christening my boy, I wash and they dress me in a fine new gown of crimson lace and cloth of gold, they put the best sheets on my great bed, and help me back onto the pillows, so that I can be arranged, like a triumphant Madonna, for congratulations. I hear the trumpets outside my room, and the tramp of many feet. They throw open the double doors to my chamber and Cecily comes in, beaming, and puts my baby Arthur into my arms. My mother gives me a beautiful cup of gold for him, the Earl of Oxford has sent a pair of gilt basins, the Earl of Derby a saltcellar of gold. Everyone comes piling into my bedchamber with gifts, kneeling to me as the mother of the next king, kneeling to him to show their loyalty. I hold him and I smile and thank people for their kindness, as I look at men who loved Richard and promised loyalty to him, and who are now smiling at me and kissing my hand and agreeing, without words, that we shall never mention those long seasons ever again. That time shall be as if it never was. We will never speak of it, though they were the happiest days of my life, and maybe the happiest days of theirs, too.

The men swear their loyalty, and pay compliments, and then my mother says quietly: “Her Grace the Queen should rest now,” and My Lady the King’s Mother says at once, so that it shall not be my mother who gives an order: “Prince Arthur must be taken to his nursery. I have everything prepared for him.”

This day marks his entry into royal life, as a Tudor prince. In a few weeks’ time he will have his own nursery palace; we will not even sleep under the same roof. I shall reenter the court as soon as I am churched and Henry will come back to my bed to make another prince for the Tudors. I look at my little son, the tiny baby that he is, in his nursemaid’s arms, and know that they are taking him from me, and that he is prince and I am queen and we are mother and child alone together no more.

Even before I am churched and out of confinement, Henry rewards us Yorks with the marriage of my sister. The timing of the announcement is a compliment to me, a reward for giving him a son; but I understand by their waiting so long that if I had died in childbed, he would have had to marry another princess of York to secure the throne. He and his mother kept Cecily unmarried in case of my death. I went into the danger of childbed with my sister marked out for my widower. Truly, My Lady plans for everything.

Cecily comes to me breathless with excitement, her face flushed as if she is in love. I am tired, my breasts hurt, my privates hurt, everything hurts as my sister dances into my rooms and declares: “He has favored me! The king has favored me! My Lady has spoken for me, and the wedding is to happen at last! I am her goddaughter, but now I am to be even closer!”

“They have set your wedding day?”

“My betrothed came to tell me himself. Sir John. I shall be Lady Welles. And he is so handsome! And so rich!”

I look at her, a hundred harsh words on the tip of my tongue. This is a man who was raised to hate our family, whose father died under our arrows at the battle of Towton when his own artillery could not fire in the snow, whose half brother Sir Richard Welles and his son Robert were executed by our father on the battlefield for treachery. Cecily’s betrothed is Lady Margaret’s half brother, a Lancastrian by birth, by inclination, and by lifelong enmity to us. He is thirty-six years old to my sister’s seventeen, he has been our enemy all his life. He must hate her. “And this makes you happy?” I ask.

She does not even hear the skepticism in my tone. “Lady Margaret herself made this wedding,” she says. “She told him that though I am a princess of York I am charming. She said that: charming. She said that I am utterly suited to be the wife of a nobleman of the Tudor court. She said I am most likely to be fertile, she even praised you for having a boy. She said I am not puffed up with false pride.”

“Did she say legitimate?” I ask dryly. “For I can never remember whether we are princesses or not at the moment.”

Finally she hears the bitterness in my voice and she pauses in her jig, takes hold of my bedpost, and swings around to look at me. “Are you jealous of me for making a marriage for love, to a nobleman, and that I come to him untouched? With the favor of My Lady?” she taunts me. “That my reputation is as good as any maid’s in the world? With no secrets behind me? No scandals that might be unearthed? Nobody can say one word against me?”

“No,” I say wearily. I could weep for the aches and pains, the seep of blood, the matching seep of tears. I am missing my baby, and I am mourning for Richard. “I am glad for you, really. I am just tired.”

“Shall I send for your mother?” Our cousin Maggie steps forwards, frowning at Cecily. “Her Grace is still recovering!” she says quietly. “She shouldn’t be disturbed.”

“I only came to tell you I am to be married, I thought you would be happy for me,” Cecily says, aggrieved. “It is you who is being so unpleasant . . .”

“I know.” I force myself to change my tone. “And I should have said that I am glad for you, and that he is a lucky man to have such a princess.”

“Father had greater plans for me than this,” she points out. “I was raised for better than this. If you don’t congratulate me, you should pity me.”

“Yes,” I reply. “But all my pity is used up on myself. It doesn’t matter, Cecily, you can’t understand how I feel. You should be happy, I am glad for you. He’s a lucky man and, as you say, handsome and wealthy, and any one of My Lady the King’s Mother’s family is always going to be a favorite.”

“We’ll marry before Christmas,” she says. “When you are churched and back at court, we’ll marry and you can give me the royal wedding gift.”

“I shall so look forward to that,” I say, and little Maggie hears the sarcasm in my voice and shoots me a hidden smile.

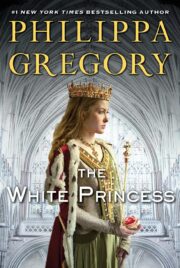

"The White Princess" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "The White Princess". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "The White Princess" друзьям в соцсетях.