“My Lady the King’s Mother is ill with fear,” I point out to her. “She thinks the English springtime is a benighted desert. Her son is all but dumb. They trust no one but their own circle and every day there are more rumors in the outside world. It’s coming, isn’t it? A new rebellion? You know the plans and you know who will lead them.” I pause and lower my voice to a whisper. “He’s on the way, isn’t he?”

My mother says nothing for a moment but walks beside me in silence, graceful as ever. She pauses and turns to me, takes a daffodil bud, and tucks it gently into my hat. “Do you think I have said nothing to you ever since your marriage about these matters because it slipped my mind?” she asks quietly.

“No, of course not.”

“Because I thought you had no interest?”

I shake my head.

“Elizabeth, on your wedding day you promised to love, honor, and obey the king. On the day of your coronation you will have to promise, before God in the most solemn and binding of vows, to be his loyal subject, the first of his loyal subjects. You will take the crown on your head, you will take the holy oil on your breast. You cannot be forsworn then. You cannot know anything that you would have to keep from him. You cannot have secrets from him.”

“He doesn’t trust me!” I burst out. “Without you ever telling me a word he already suspects me of knowing a whole conspiracy and keeping it secret. Over and over again he asks me what I know, over and over again he warns me that he is making allowances for us. His mother is certain that I am a traitor to him, and I believe that he thinks so too.”

“He will come to trust you, perhaps,” she says. “If you have years together. You may grow to be a loving husband and wife, if you have long enough. And if I never tell you anything, then there will never be a moment where you have to lie to him. Or worse—never a moment when you have to choose where your loyalties lie. I wouldn’t want you to have to choose between your father’s family and your husband’s. I wouldn’t want you to have to choose between the claims of your little son and another.”

I am horrified at the thought of having to choose between Tudor and York. “But if I know nothing, then I am like a leaf on the water, I go wherever the current takes me. I don’t act, I do nothing.”

She smiles. “Yes. Why don’t you let the river take you? And we’ll see what she says.”

We turn in silence and head back along the riverbank to Sheen, the beautiful palace of many towers which dominates the curve of the river. As we walk towards the palace I see half a dozen horses gallop up to the king’s private door. The men dismount, and one pulls off his hat and goes inside.

My mother leads the ladies past the men-at-arms, and graciously acknowledges their salute. “You look weary,” she says pleasantly. “Come far?”

“Without stopping for sleep, all the way from Flanders,” one boasts. “We rode as if the devil was behind us.”

“Did you?”

“But he’s not behind us, he’s before us,” he confides quietly. “Ahead of us, and ahead of His Grace, and out and about raising an army while the rest of us are amazed.”

“That’s enough,” another man says. He pulls off his hat to me and to my mother. “I apologize, Your Grace. He’s been breathless for so long he has to talk now.”

My mother smiles on the man and on his captain. “Oh, that’s all right,” she says.

Within an hour the king has called a meeting of his inner council, the men he turns to when he is in danger. Jasper Tudor is there, his red head bowed, his grizzled eyebrows knitting together with worry at the threat to his nephew, to his line. The Earl of Oxford walks arm in arm with Henry, discussing mustering men, and which counties can be trusted and which must not be alarmed. John de la Pole comes into the council chamber on the heels of his fiercely loyal father, and the other friends and family follow: the Stanleys, the Courtenays, John Morton the archbishop, Reginald Bray, who is My Lady’s steward—all the men who put Henry Tudor on the throne and now find it is hard to keep him there.

I go to the nursery. I find My Lady the King’s Mother sitting in the big chair in the corner, watching the nurse changing the baby’s clout and wrapping him tight in his swaddling clothes. It is unusual for her to come here, but I see from her strained face and the beads in her hand that she is praying for his safety.

“Is it bad news?” I ask quietly.

She looks at me reproachfully, as if it is all my fault. “They say that the Duchess of Burgundy, your aunt, has found a general who will take her pay and do her bidding,” she says. “They say he is all but unbeatable.”

“A general?”

“And he is recruiting an army.”

“Will they come here?” I whisper. I look out of the window to the river and the quiet fields beyond.

“No,” she says determinedly. “For Jasper will stop them, Henry will stop them, and God Himself will stop them.”

On my way to my mother’s chambers, I hurry past the king’s rooms, but the door to the great presence chamber is still closed. He has most of the lords gathered together, and they will be frantically trying to judge what new threat this presents to the Tudor throne, how much they should fear, what they should do.

I find I am quickening my pace, my hand to my mouth. I am afraid of what is threatening us, and I am also afraid of the defense that Henry will mount against his own people that might be more violent and deadly than an actual invasion.

My mother’s rooms are closed too, the doors tightly shut, and there is no servant waiting outside to swing open the doors for me. The place is quiet—too quiet. I push open the door myself, and look at the empty room spread out in front of me like a tableau in a pageant before the actors arrive. None of her ladies is here, her musicians are absent, a lute leaning against a wall. All her things are untouched: her chairs, her tapestries, her book on a table, her sewing in a box; but she is missing. It seems as if she has gone.

Like a child, I can’t believe it. I say, “Mother? Lady Mother?” and I step into the quiet sunny presence chamber and look all around me.

I open the door to her privy chamber and it is empty too. There is a scrap of sewing left on one of the chairs, and a ribbon on the window seat, but nothing else. Helplessly, I pick up the ribbon as if it might be a sign, I twist it in my fingers. I cannot believe how quiet it is. The corner of a tapestry stirs in the draft from the door, the only movement in the room. Outside a wood pigeon coos, but that is the only sound. I say again: “Mama? Lady Mother?”

I tap on the door to her bedroom and swing it open, but I don’t expect to find her there. Her bed is stripped of her linen, the mattress lies bare. The wooden posts are stripped of her bed curtains. Wherever she has gone, she has taken her bedding with her. I open the chest at the foot of her bed, and find her clothes have gone too. I turn to the table where she sits while her maid combs her hair; her silvered mirror has gone, her ivory combs, her golden hairpins, her cut-glass phial of oil of lilies.

Her rooms are empty. It is like an enchantment; she has silently disappeared, in the space of a morning, and all in a moment.

I turn on my heel at once and go to the best rooms, the queen’s rooms, where My Lady the King’s Mother spends her days among her women, running her great estates, maintaining her power while her women sew shirts for the poor and listen to readings from the Bible. Her rooms are busy with people coming and going; I can hear the buzz of happy noise through the doors as I walk towards them, and when they are swung open and I am announced, I enter to see My Lady, seated under a cloth of gold like a queen, while around her are her own ladies and among them my mother’s companions, merged into one great court. My mother’s ladies look at me wide-eyed, as if they would whisper secrets to me; but whoever has taken my mother has made sure that they are silent.

“My Lady,” I say, sweeping her the smallest of curtseys due to my mother-in-law and mother to the king. She rises and executes the tiniest of bobs, and then we kiss each other’s cold cheeks. Her lips barely touch me, as I hold my breath as if I don’t want to inhale the smoky smell of incense that always hangs in her veiled headdress. We step back and take the measure of the other.

“Where is my mother?” I ask flatly.

She looks grave as if she were not ready to dance for joy. “Perhaps you should speak with my son the king.”

“He is in his chambers with his council. I don’t want to disturb him. But I shall do so and tell him that you sent me, if that is what you wish. Or can you tell me where my mother is. Or don’t you know? Are you just pretending to knowledge?”

“Of course I know!” she says, instantly affronted. She looks around at the avid faces and gestures to me that we should go through to an inner chamber, where we can talk alone. I follow her. As I go by my mother’s ladies I see that some of them are missing; my half sister Grace, my father’s bastard, is not here. I hope she has gone with my mother, wherever she is.

My Lady the King’s Mother closes the door herself, and gestures that I should sit. Careful of protocol, even now, we sit simultaneously.

“Where is my mother?” I say again.

“She was responsible for the rebellion,” My Lady says quietly. “She sent money and servants to Francis Lovell, she had messages from him. She knew what he was doing and she advised and supported him. She told him which households would hide him and give him men and arms outside York. While I was planning the king’s royal progress, she was planning a rebellion against him, planning to ambush him on his very route. She is the enemy of your husband and your son. I am very sorry for you, Elizabeth.”

I bristle, hardly hearing her. “I don’t need your pity!”

“You do,” she presses on. “For it is you and your husband that your own mother is plotting against. It is your death and downfall she is planning. She worked for Lovell’s rebellion and now she writes secretly to her sister-in-law in Flanders urging her to invade.”

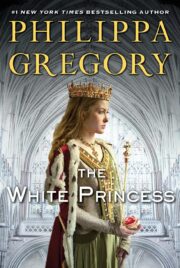

"The White Princess" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "The White Princess". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "The White Princess" друзьям в соцсетях.