“No. She would not.”

“We have proof,” she says. “There’s no doubt. I am sorry for it. This is a great shame to fall on you and your family. A disgrace to your family name.”

“Where is she?” I ask. My greatest fear is that they have taken her to the Tower, that she will be kept where her sons were held, and that she won’t come out either.

“She has retired from the world,” Lady Margaret says solemnly.

“What?”

“She has seen the error of her ways and gone to confess her sins and live with the good sisters at Bermondsey Abbey. She has chosen to live there. When my son put the evidence of her conspiracy before her, she accepted that she had sinned and that she would have to go.”

“I want to see her.”

“Certainly, you can go to see her,” Lady Margaret says quietly. “Of course.” I see a little hope flare in her veiled eyes. “You could stay with her.”

“Of course I’m not going to stay in Bermondsey Abbey. I shall visit her, and I shall speak with Henry, as she must come back to court.”

“She cannot have wealth and influence,” Lady Margaret says. “She would use it against your husband and your son. I know that you love her dearly, but, Elizabeth—she has become your enemy. She is no mother to you and your sisters anymore. She was providing funds to the men who hope to throw down the Tudor throne; she was giving them advice, sending them messages. She was plotting with Duchess Margaret, who is mustering an army. She was living with us, playing with your child, our precious prince, seeing you daily, and yet working for our destruction.”

I rise from my chair and go to the window. Outside the first swallows of summer are skimming along the surface of the river, twisting and turning in flight, their bellies a flash of cream as if they are glad to be dipping their beaks into their own reflections, playing with the sweet water of the Thames. I turn back. “Lady Margaret, my mother is not dishonorable. And she would never do anything to hurt me.”

Slowly she shakes her head. “She insisted that you marry my son,” she says. “She demanded it, as the price of her loyalty. She was present at the birth of the prince. She was honored at his christening, she is his godmother. We have honored her and housed her and paid her. But now she plots against her own grandson’s inheritance and strives to put another on his throne. This is dishonorable, Elizabeth. You cannot deny that she is playing a double game, a shameful game.”

I put my hands over my face, so that I can shut out her expression. If she looked triumphant I would simply hate her, but she looks horrified, as if she feels, like me, that everything we have been trying to do is going to be pulled apart.

“She and I have not always agreed.” She appeals to me. “But I did not see her leave court with any pleasure. This is a disaster for us as well as for her. I hoped we would make one family, one royal family standing together. But she was always pretending. She has been untrue to us.”

I can’t defend her; I bow my head and a little moan of horror escapes through my gritted teeth.

“She’s not at peace,” Lady Margaret concludes. “She is going on and on fighting the war that you Yorks have lost. She’s not made peace with us, and now she’s at war with you, her own daughter.”

I give a little wail and sink down in the window seat, my hands hiding my face. There is a silence as Lady Margaret crosses the room and seats herself heavily beside me.

“It’s for her son, isn’t it?” she asks wearily. “That’s the only claim she would fight for in preference to yours. That’s the only pretender that she would put against her grandson. She loves Arthur as well as we do, I know that. The only claim she would favor over his would be that of her own son. She must think that one of her boys, Richard or Edward, is still alive and she hopes to put him on the throne.”

“I don’t know, I don’t know!” I am crying now, I can hardly speak. I can hardly hear her through my sobs.

“Well, who is it?” she suddenly shouts, flashing out into rage. “Who else could it be? Who could she put above her own grandson? Who can she prefer to our Prince Arthur? Arthur that was born at Winchester, Arthur of Camelot? Who can she prefer to him?”

Dumbly, I shake my head. I can feel the hot tears pooling in my icy hands and making my face wet.

“She would throw you down for no one else,” Lady Margaret whispers. “Of course it is one of the boys. Tell me, Elizabeth. Tell me all that you know so that we can make your son, Arthur, safe in his inheritance. Does your mother have one of her boys hidden somewhere? Is he with your aunt in Flanders?”

“I don’t know,” I say helplessly. “She would never tell me anything. I said I don’t know, and truly, I don’t know. She made sure that there was never anything that I could tell you. She did not want me ever to have an inquisition like this. She tried to protect me from it, so I don’t know.”

Henry comes to my rooms with his court before dinner, a tight, unconvincing smile on his face, playing the part of a king, trying to hide his fear that he is losing everything.

“I’ll talk with you later,” he says in a hard undertone. “When I come to your room tonight.”

“My lord . . .” I whisper.

“Not now,” he says firmly. “Everyone needs to see that we are united, that we are as one.”

“My mother cannot be held against her will,” I stipulate. I think of my cousin in the Tower, my mother in Bermondsey Abbey. “I cannot tolerate my family being held. Whatever you suspect. I will not bear it.”

“Tonight,” he says. “When I come to your rooms. I’ll explain.”

My cousin Maggie gives me one single aghast look and then comes behind me, picks up my train, and straightens it out as my husband takes my hand and leads me into dinner before the court, and I smile, as I must do, to the left and to the right, and wonder what my mother will have for her dinner tonight, while the court, that once was her court, is merry.

At least Henry comes to me promptly, straight after chapel, dressed for bed, and the lords who escort him to my bedroom quickly withdraw to leave us alone, and my cousin Maggie waits only to see if there is anything that we need, and then she goes too, with one wide-eyed glance at me, as if she fears that next morning I will have disappeared as well.

“I don’t mean your mother to be enclosed,” Henry says briskly. “And I won’t put her on trial if I can avoid it.”

“What has she done?” I demand. I cannot maintain the pretence that she is innocent of everything.

“Do you mean that?” he shoots back at me. “Or are you trying to discover how much I know?”

I give a little exclamation, and turn away from him.

“Sit down, sit down,” he says. He comes after me and takes my hand and leads me to the fireside chair where we used to sit so comfortably. He presses me down into the seat and pats my flushed cheek. For a moment I long to throw myself into his arms and cry on his chest and tell him that I know nothing for sure, but that I fear everything just as he does. That I am torn between love for my mother and my lost brothers, and love for my son. That I cannot be expected to choose the next King of England and finally, most puzzling of all for me, I would give anything in the world to see my beloved brother again and know that he is safe. I would give anything but the throne of England, anything but Henry’s crown.

“I don’t know all of it,” he says, sitting heavily opposite me, his chin on his fist, looking at the flames. “That’s the worst thing: I don’t know all of it. But she has been writing to your aunt Margaret in Flanders, and Margaret is mustering an army against us. Your mother has been in contact with all the old York families, those of her household, those who remember your father or your uncle, calling them to be ready for when Margaret’s army lands. She has been writing to men in exile, to men in hiding. She has been whispering with her sister-in-law, Elizabeth—John de la Pole’s mother. She’s even been visiting your grandmother Duchess Cecily, her mother-in-law. They were at daggers drawn for all of her marriage but now they are in alliance against a greater enemy: me. I know that she was writing to Francis Lovell. I have seen the letters. She was behind his rebellion, I have evidence for that now. I even know how much she sent him to equip his army. It was the money I gave her, the allowance that I granted her. All this I know, I have seen it with my own eyes. I have held her letters in my own hands. There is no doubt.”

He exhales wearily and takes a sip of his drink. I look at him in horror. This evidence is enough to have my mother locked up for the rest of her life. If she were a man, they would behead her for treason.

“That’s not the worst of it,” he goes on grimly. “There is probably more; but I don’t know what else she’s been doing. I don’t know all her allies, I don’t know her most secret plans. I don’t dare to think.”

“Henry, what do you fear?” I whisper. “What do you fear that she has been doing, when you look like this?”

He looks as if he is being harried beyond bearing. “I don’t know what to fear,” he says. “Your aunt the Dowager Duchess of Burgundy is raising an army, a great army against me, I know that much.”

“She is?”

He nods. “And your mother was raising rebels at home. Today I had my council here. I’m in command of the lords, I’m sure of that. At any rate . . . they all swore fealty. But who can I trust if your mother and your aunt put an army in the field, and at the head of it is—” He breaks off.

“Is who?” I ask. “Who do you fear might lead such an invasion?”

He looks away from me. “I think you know.”

I cross the room and take his hand, horrified. “Truly, I don’t know.”

He holds my hand very tightly and stares into my eyes as if trying to read my thoughts, as if he wants more than anything else in the world to know he can trust me, his wife and the mother of his child.

“Do you think John de la Pole would turn his coat and lead the army against you?” I ask, naming my own cousin, Richard’s heir. “Is it him you fear?”

“Do you know anything against him?”

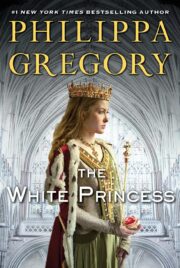

"The White Princess" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "The White Princess". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "The White Princess" друзьям в соцсетях.