“Ah, so he thinks we’re invading the east coast,” she says gleefully. “So that’s what he’s expecting.”

“What?”

“He’s not going to Norwich for the pleasure of the feast. He’s going so that he can prepare the east coast for invasion.”

“They will invade? From Flanders?”

She puts a kiss on my forehead, completely ignoring my fearful questions. “Now don’t you worry about it,” she says. “You don’t need to know.”

She walks with me to the gatehouse, and then round the outside walls to where the pier runs out into the Neckinger River and my boat is waiting, bobbing on the rising tide. She kisses me and I kneel for her blessing and feel her warm hand rest gently on my hood. “God bless you,” she says sweetly. “Come and see me when you return from Norwich, if you are able to come, if you are allowed.”

“I’m going to be alone at court without you,” I remind her. “I have Cecily and I have Anne, and Maggie, but I feel alone without you. My little sisters miss you too. And My Lady the King’s Mother thinks I am plotting with you and my husband doubts me. And I have to live there, with them, all of them, being watched by them all the time, without you.”

“Not for long,” she says, her buoyant confidence unchanged. “And very soon you will come to me or—who knows—I will find a way to come to you.”

We get back to Richmond on the inflowing tide and as soon as we round the bend in the river I can see a tall slight figure waiting on the landing stage. It is the king. It is Henry. I recognize him from far away, and I don’t know whether to tell the wherry to just turn around and row away, or to go on. I should have known that he would know where I was. My uncle Edward warned me that this is a king who knows everything. I should have known that he would not accept the lie of illness without questioning my cousin Margaret, and demanding to see me.

His mother is not at his side, nor any of his court. He is standing alone like an anxious husband, not like a suspicious king. As the little boat nudges up against the wooden pilings and my groom jumps ashore, Henry puts him to one side and helps me out of the boat himself. He throws a coin to the boatman, who rings it against his teeth as if surprised to find that it is good, and then disappears into the mist of the twilight river.

“You should have told me you wanted to go and I would have sent you more comfortably on the barge,” Henry says shortly.

“I am sorry. I thought you would not want me to visit.”

“And so you thought you would get out and back without my knowing?”

I nod. There is no point denying it. Obviously I had hoped that he would not know. “Because you don’t trust me,” he says flatly. “Because you don’t think that I would let you visit her, if it was safe for you to do so. You prefer to deceive me and creep out like a spy to meet my enemy in secret.”

I say nothing. He tucks my hand into the crook of his elbow as if we were a loving husband and wife, and he makes me walk, stride by stride, with him.

“And did you find your mother comfortably housed? And well?”

I nod. “Yes. I thank you.”

“And did she tell you what she has been doing?”

“No.” I hesitate. “She tells me nothing. I told her that we were going to Norwich, I hope that wasn’t wrong?”

For a moment his hard gaze at me is softened, as if he is sorry for the tearing apart of my loyalties; but then he speaks bitterly. “No. It doesn’t matter. She will have other spies set around me as well as you. She probably knew already. What did she ask you?”

It is like a nightmare, reviewing my conversation with my mother and wondering what will incriminate her, or even incriminate me. “Almost nothing,” I answer. “She asked me if John de la Pole had left court, and I said yes.”

“Did she hazard a guess as to why he had gone? Did she know where he had gone?”

I shake my head. “I told her that it was thought that he has gone to Flanders,” I confess.

“Did she not know already?”

I shrug. “I don’t know.”

“Was he expected?”

“I don’t know.”

“Will his family follow him, do you think? His brother Edmund? His mother, Elizabeth, your aunt? His father? Are they all faithless, though I have trusted them and taken them into my court and listened to their counsels? Will they just take note of everything I said and take it to their kinsmen, my enemies?”

I shake my head again. “I don’t know.”

He releases my hand to step back and look at me, his dark eyes unsmiling and suspicious, his face hard. “When I think of the fortune that was spent on your education, Elizabeth, I am really amazed at how little you know.”

ST. MARY’S IN THE FIELDS, NORWICH, SUMMER 1487

The town is the richest in the kingdom, and every guild based on the wool business dresses up in the finest robes and pays for costumes, scenery, and horses to make a massive procession with merchants, masters, and apprentices in solemn order to celebrate the feast of the church and their own importance.

I stand beside Henry, both in our best robes as we watch the long procession, each guild headed by a gorgeously embroidered banner and a litter carrying a display to celebrate their work or show their patron saint. Now and then I can see Henry glance sideways at me. He is watching me as the guilds go by. “You smile at someone when he catches your eye,” he says suddenly.

I am surprised. “Just out of courtesy,” I say defensively. “It means nothing.”

“No, I know. It’s just that you look at them as if you wish them well; you smile in a friendly way.”

I cannot understand what he is saying. “Yes, of course, my lord. I’m enjoying the procession.”

“Enjoying it?” he queries as if this explains everything. “You like this?”

I nod, though he makes me feel almost guilty to have a moment of pleasure. “Who would not? It’s so rich and varied, and the tableaux so well made, and the singing! I don’t think I’ve ever heard such music.”

He shakes his head in impatience at himself, and then remembers everyone is watching us and raises a hand to a passing litter with a splendid castle built out of gold-painted wood. “I can’t just enjoy it,” he says. “I keep thinking that these people put on this show, but what are they thinking in their hearts? They might smile and wave at us and doff their hats, but do they truly accept my rule?”

A little child, dressed as a cherub, waves at me from a pillow of white on blue, representing a cloud. I smile and blow him a kiss, which makes him wriggle with delight.

“But you just enjoy it,” Henry says, as if pleasure was a puzzle to him.

I laugh. “Ah well,” I say. “I was raised in a happy court and my father loved nothing better than a joust or a play or a celebration. We were always making music and dancing. I can’t help but enjoy a spectacle, and this is as fine as anything I have ever seen.”

“You forget your worries?” he asks me.

I consider. “For a moment I do. D’you think that makes me very foolish?”

Ruefully, he smiles. “No. I think you were born and raised to be a merry woman. It is a pity that so much sorrow has come into your life.”

There is a roar of cannon, in salute from the castle, and I see Henry flinch at the noise, and then grit his teeth and master himself.

“Are you well, my lord husband?” I ask him quietly. “Clearly you’re not easily amused like me.”

The face he turns to me is pale. “Troubled,” he says shortly, and I remember with a sudden pulse of dread that my mother said that the court was at Norwich because Henry expects an invasion on the east coast, and that I have been smiling and waving like a fool while my husband fears for his life.

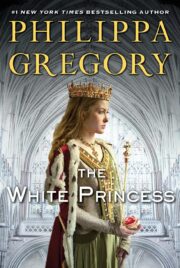

"The White Princess" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "The White Princess". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "The White Princess" друзьям в соцсетях.